The Alistister City Museum’s grand atrium still smells like old varnish and floor polish, a stately relic of Baton Rouge’s past. For fifty years, visitors shuffled past glass cases of muskets and faded flags, pausing at a “wax figure” of an unnamed Black Union soldier that docents praised for its haunting realism. It stood in a dim alcove of the Civil War wing, hands clasped on a rifle, eyes set on a point just above the crowd. This spring, a new curator looked a little closer—and uncovered what appears to be a fifty-year-old cold case hiding in plain sight.

According to internal records reviewed during a comprehensive audit, the figure—accessioned as item 44-7B—entered the museum’s collection in 1974 with almost no documentation. No creator. No donor. No provenance. For a public institution that meticulously logged silver lockets and paper ephemera, “N/A” stamped across a human-scale “statue” read less like a clerical lapse and more like a warning. That warning reached the right set of eyes. The museum’s newly appointed curator, Dr. Maya Vincent, 34, arrived with a mandate to modernize the archives and re-examine the stories the museum told—and the ones it didn’t.

Her inventory took her from the wood-paneled office once occupied by her predecessor to the basement ledgers that acted as the museum’s memory. The Civil War collection’s paper trail was stale but serviceable—until 44-7B. The file was a single index card. The ledger line was a ghost. In a field where provenance is the backbone of trust, that omission was a red flag. When Dr. Vincent stepped into the dim hall to see the “wax figure” for herself, the red flag became a klaxon.

From a distance, the soldier could be mistaken for any mid-century diorama mannequin. Up close, the illusion broke in the opposite direction. The skin appeared to absorb light rather than reflect it. The pores, the hairline at the temple, the fine ridges in the nails—details that most figures simulate with paint—seemed disturbingly organic. The uncanny valley is a known effect in museum display, but this crossed a line that felt less like craft and more like violation.

Dr. Vincent sought answers from the one person who had been there in 1974: the longtime curator who’d retired after a half-century tenure. His response—“just an old wax model from an eccentric local artist, didn’t want credit”—fell apart under even basic scrutiny. There was no name to crosscheck, no donor to contact, no invoices or conservation notes to corroborate the claim. When she pressed politely, the call ended abruptly with an admonition to focus on the future, not “settled” dust.

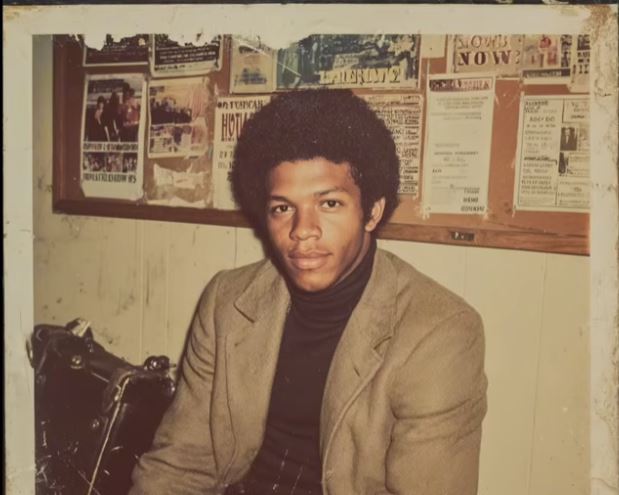

If the files were silent, the public record wouldn’t be. Dr. Vincent, a historian by training, dug through microfilm at the public library, starting with the year before the accession. In the pages of a Black community newspaper, she found a name that had electrified the city in 1973: Lionel “Lion” Vance, a 28-year-old jazz trumpeter and housing rights activist. His face was everywhere in the archives—smiling at rallies, speaking at council meetings—until it wasn’t. In the fall of 1973, Vance vanished. His car was found by the river, trumpet still in the trunk. A brief, dismissive official narrative suggested he’d fled to avoid unspecified trouble. The investigation closed in three weeks.

The timeline was jarring. A prominent Black activist goes missing in late 1973. Less than a year later, a hyper-real “figure” with no provenance appears in a city museum. Correlation isn’t proof. But in a 1972 profile, the reporter noted a distinctive crescent-shaped scar just over Vance’s left eyebrow from a childhood fall—“my personal moon,” he’d joked. Back in the museum, the soldier’s forage cap sat low on the brow, obscuring that very spot.

In violation of both nerves and protocol, Dr. Vincent returned after hours and nudged the brim. Under the cap: a faint, silvery crescent. The hypothesis suddenly had a testable path. If this was more than an exhibit—if it was a person—there would be one way to know for certain.

What followed was a decision that, according to sources familiar with the situation, Dr. Vincent did not take lightly. Working quietly with a trusted hospital radiology specialist, she arranged for a non-invasive, after-hours digital X-ray. The equipment, positioned on either side of the figure, emitted a low hum in the empty hall as the scan captured a cross-section of the “wax.” On the laptop, the image resolved not into wire and plaster but into the unmistakable lattice of a human rib cage. The fine bones of the hand, perfectly aligned inside the figure’s outer layer, left little room for doubt: this was a preserved human body.

The scan revealed something else. Lodged beneath the left ribs, just off the sternum, was a dense, round object with the metallic signature of a bullet. It was small caliber. It did not belong there. If the image is what it appears to be, this exhibit was more than a moral and institutional failure; it was potentially a crime scene.

It is here that careful reporting and clear language matter, especially in a story with explosive implications. The museum has not yet publicly confirmed the X-ray findings. The longtime curator named in internal conversations has not responded to detailed questions about the 1974 acquisition. The original police file on Vance’s disappearance, as preserved in municipal archives, is thin and does not indicate that forensic avenues were explored at the time. Any definitive identification of the remains would require legal custody, forensic testing, and notification of next of kin. Those steps, by necessity, involve law enforcement and medical examiners and will take time.

What is not in dispute is the context. The “wax figure” entered the collection with no documented creator or donor, a process failure that would be unacceptable by any standard, then or now. The exhibit was displayed for decades without the kind of periodic condition reporting and materials analysis that modern museums use to protect visitors and collections alike. The community’s pain around Vance’s disappearance was real. His case was public, and it faded from the front page with a speed that is itself a story about who is believed and who is not.

To tell this story in a way that is both gripping and responsible, details must be anchored to what can be verified. The ledger gap is real. The missing-person coverage is a matter of record. The scar described in the 1972 profile exists in the same location on the figure. A digital X-ray image, according to a source with direct knowledge, shows human skeletal structures and a foreign metallic object consistent with a projectile. Each of these data points can be corroborated independently by authorities and experts. Avoiding embellishment—no insinuations about motive, no names of uncharged individuals presented as villains—keeps the narrative compelling without turning it into speculation.

The human stakes are what make the story hard to look away from. If confirmed, the museum’s most chilling artifact was a man with a name and a family, a community that mourned him, and a city that learned to live with his absence. An institution tasked with preserving history may have, wittingly or not, preserved an injustice instead—elevating a body to an object and a life to a label. The weight of that error, or that act, demands transparency: how the figure arrived, who approved its display, what standards failed, and what safeguards will prevent anything like it from ever happening again.

It also demands care. Museums change because people inside them choose accountability. If Dr. Vincent’s discovery holds, it will be because a curator refused to accept “N/A” as an answer, because a technician trusted her judgment, and because the public recognizes that the past is not inert—it is a record we have to earn, not just inherit. The next steps should be formal and visible: secure the exhibit as potential evidence; invite independent forensic analysis; notify Vance’s family if living relatives can be located; and appoint an outside panel to review the museum’s 1970s acquisitions and policies. A public report can rebuild trust by showing the work.

Baton Rouge knows the power of stories—how they’re told, who gets to tell them, and what happens when they’re silenced. For decades, schoolchildren stood in front of a soldier and stared into a stranger’s eyes. If those eyes belonged to Lionel Vance, the city owes him more than a plaque. It owes him his name, a truthful accounting, and a path to justice, even fifty years late. The realism that once drew whispers in a dim gallery was never a technical triumph. It was a plea, waiting for someone to listen.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load