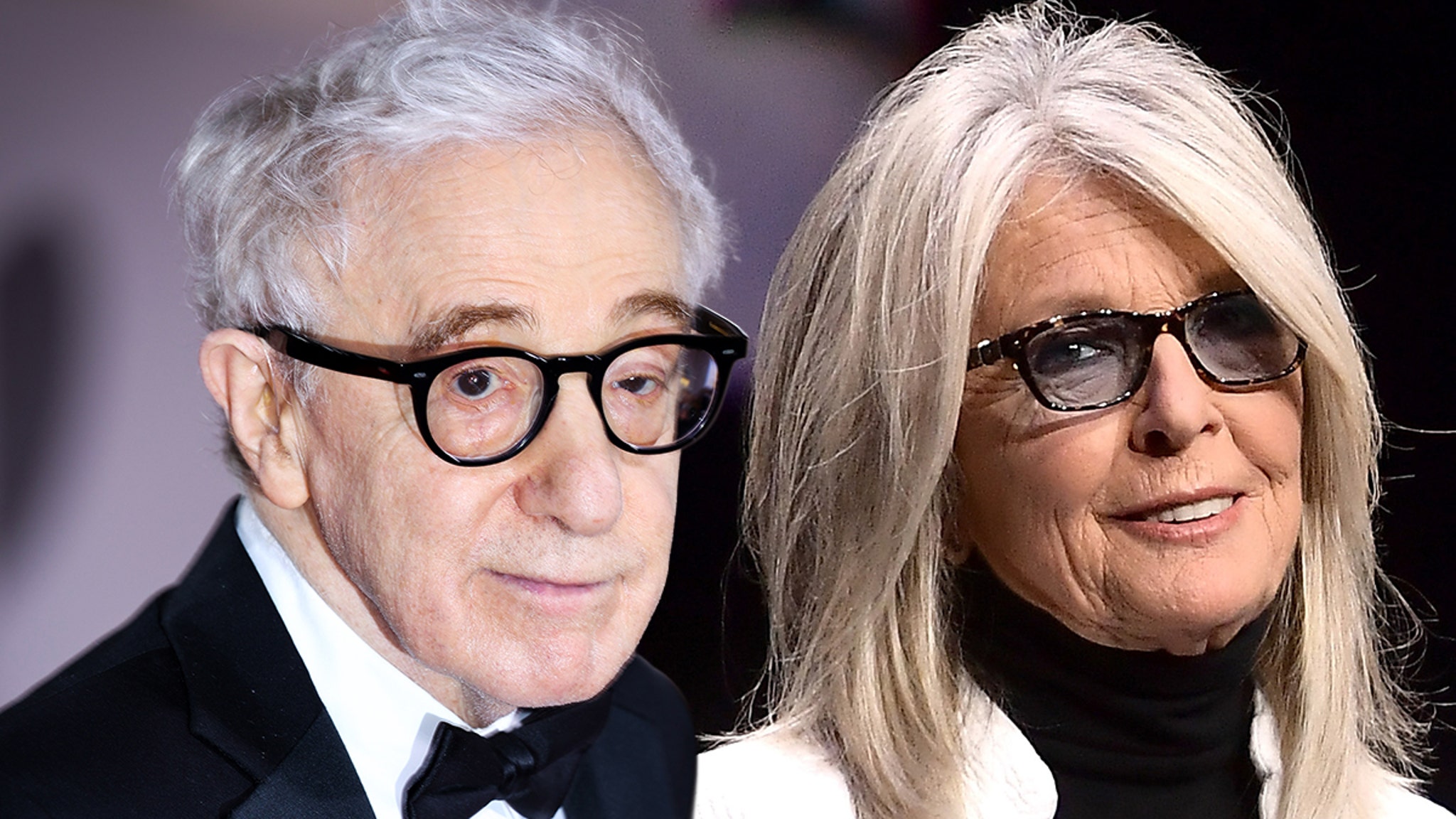

Two days after Diane Keaton’s death, Woody Allen broke his silence with a tribute that affirmed what many long suspected about one of Hollywood’s most enduring creative bonds. Beneath the nervous wit that made Annie Hall a touchstone and the decades of public reserve that defined their separate paths, he described a steady line of affection and artistic reliance. In his remembrance, he called Keaton the emotional and artistic compass of his career, the person whose laughter guided the tone of his comedies and whose opinion he most trusted. For a generation of moviegoers, the sentiment felt less like a revelation than a confirmation of something already embedded in the films they made together. The confession, as he framed it, belonged to private memory; the evidence had always been on screen.

Keaton’s path to that screen presence began far from the mythology. At nineteen, newly arrived in New York from Santa Ana, California, she was an aspiring actor with a practical streak and a curious mind. She studied at the Neighborhood Playhouse under Sanford Meisner, absorbing a method that prized truthful reactions and felt moments over polished poses. The city was alive with Off-Broadway energy and rule-breaking ideas. Keaton waited tables, auditioned relentlessly, and found her way into Hair at the height of its cultural shock. She famously refused the show’s nude moment, an early sign of the boundary-setting that would mark her values throughout her life. The refusal did not dim her momentum—it sharpened a persona that could join a movement without dissolving into it.

In 1969, she auditioned for Woody Allen’s Play It Again, Sam on Broadway and landed a role that would change careers—her own and his. Allen, already a rising comic voice turning toward film and theater, needed an actress who could be both a dream figure and a disarming realist. Keaton’s offbeat timing and unforced warmth delivered both. The play was a hit, running well over a year, and Keaton earned a Tony nomination. Onstage chemistry evolved into a private relationship and then, crucially for posterity, into a creative partnership that survived its romantic phase. The on-screen run that followed helped reshape American comedy in the 1970s.

Play It Again, Sam made the jump to film in 1972; Sleeper in 1973 showed how nimble she could be across farce; Love and Death in 1975 paired her deadpan intelligence with Allen’s philosophical sendups. Each film refined a balance that would define their best work together: his anxious, cerebral humor grounded by her spontaneous humanity, her ability to shift from a hesitant pause to a full-chested laugh that made neurotic confessions feel tender rather than brittle. By the time they arrived at Annie Hall in 1977, they had discovered what they did best—build a love story out of idiosyncrasies and what-ifs, crafted from the texture of a life both shared and separate.

Annie Hall, famously re-edited from a wider, stranger draft into a love story told through memory, depends on Keaton’s performance in ways that remain hard to overstate. The character—named for Keaton’s own nickname and birth surname—moved with the rhythms of a person rather than a trope: shy, sparky, capable of disappearing into uncertainty and then disarming a room with a single, unpretentious phrase. Critics called it a revelation. The film changed Allen’s reputation from a farceur to a filmmaker of feeling and self-examination, and it made Keaton a star, complete with a fashion signature that spilled out of the frame and into closets across the country. When she accepted the Best Actress Oscar, the suit she wore was a knowing nod to a character that had already become a social shorthand.

Keaton’s tribute-era reputation as Allen’s muse can obscure what came next. After Annie Hall, she took a series of risks that widened the field for what a leading American actress could do. She moved from romance to the unsettling urban peril of Looking for Mr. Goodbar, a choice that surprised those who expected more Annie and less ambivalence. Manhattan returned her to Allen’s world in a darker key—wiser, more complicated. Then came Reds, Warren Beatty’s ambitious epic, which cast Keaton as Louise Bryant, not just a romantic foil but a thinker with her own stubborn, beating heart. The role earned her a second Oscar nomination and reaffirmed the range she was intent on claiming.

The 1980s and 1990s saw Keaton toggling between intimate dramas and mainstream comedies with a calm steadiness that made her a reliable presence—Shoot the Moon, Crimes of the Heart, Baby Boom, her return to the Corleone saga in The Godfather Part III, and the warmly received Father of the Bride films. She also directed, wrote, and photographed, building a body of work that reflected a curiosity about homes and memory, about how people arrange their lives and preserve their stories. Later roles—Something’s Gotta Give, The Family Stone, Book Club and its sequel—kept her on screens when the industry too often sidelines women past a certain age. She did not mystify longevity; she practiced it.

The private life that played behind this public arc was as deliberately drawn as her roles. She never married. She adopted two children in midlife and kept their world as free from the usual edges of celebrity as she could. She spoke candidly about her struggles with bulimia in her twenties, about the long shadow of her mother’s dementia, and about choosing independence out of self-knowledge rather than denial. She cherished intense relationships—with Allen, with Beatty, with Al Pacino—that reshaped the films they made and kept their friendships alive after the romances ended. What made those stories compelling, in recollection, wasn’t scandal; it was the consistent tone of care. Even when public controversies consumed Allen’s later years, Keaton maintained a measured silence when she lacked firsthand knowledge, a stance that read to some as loyalty and to others as restraint. What remained constant was the baseline of respect she and Allen afforded each other’s work.

The final stretch of Keaton’s life, as colleagues have described it, was marked by the same dry humor and a gentleness that had always been her signature, even through frailty. When news of her death arrived—California, bacterial pneumonia, age seventy-nine—tributes poured in from collaborators, critics, and fans who had grown up on her movies, learned to dress from her characters, and counted her as proof that you can be original without apology. Allen’s reflection, offered two days later, landed with a particular resonance. He wrote of an enchantment that never faded, of a confidante whose counsel he awaited more than reviews, and of a laugh that still echoed in his head. The line many quoted—about the world being drearier without her—read plainly. The sentiment was not crafted for effect; it sounded like the way he talked when he thought no one would edit him.

For readers wary of another round of romanticized Hollywood myth-making, the facts are clear enough. Keaton’s training and early choices formed a distinct acting philosophy grounded in listening. Her collaborations with Allen produced four of the decade’s most influential comedies and shifted his trajectory. She broadened her career immediately after Annie Hall rather than coasting on a single persona. Her influence on fashion and the on-screen idea of the modern American woman is measurable—an ensemble that normalized an androgynous ease, a posture that invited intelligence rather than demanding seduction. She wrote, photographed, directed. She raised two children. She spoke frankly about aging, power, vulnerability, and the daily work of building a private life that didn’t require public approval.

Allen’s tribute did not inflate her importance; it echoed what the record shows. He credited her as a compass because her instincts repeatedly pulled his work toward recognizable life. In a famous line often applied to their films, the joke lands better when the heart is true. Keaton was the truth-teller—sometimes with a shrug, sometimes with a stammer, always with a refusal to make herself into a marble statue. You can feel it in the way Annie Hall says “la-di-da” without irony, or in the way Mary in Manhattan cuts to the bone with a single observation. That tone—affectionate, disarming, exact—shaped how audiences learned to hear Allen’s characters and, by extension, how American film absorbed neurosis as a comedic language rather than a pathology.

If there is a risk in memorializing a partnership like theirs, it lies in reducing an artist to her relationships. Keaton did not belong to Woody Allen, or to Warren Beatty, or to Al Pacino. She belonged to the work and to the life she constructed around it, a life that allowed her to be close to difficult men without being defined by them, to play lovers on screen and negotiate boundaries off it. She once said that she didn’t want to give up who she was. Taken seriously, that sentence reads like a template for how she made decisions in an industry built on compromise.

The tributes that will follow—industry reels, retrospective screenings, think pieces linking her to shifts in American taste—will locate Keaton in familiar cultural milestones. That is one kind of truth. Another is smaller and, perhaps, closer to the long-term legacy: a way of being funny without cruelty, of being stylish without pretense, of being serious about craft without taking oneself too seriously. The country loved her for that blend. Allen’s remembrance, however personal, underlines a broader public knowledge: she made the people around her braver in their choices. That is why colleagues used words like “fearless” to describe her on demanding shoots and why she seemed, even in calm scenes, like a person constantly discovering better versions of what a moment could be.

In grief, the temptation is always to simplify. Diane Keaton resists that, even now. She is the indie actor who turned mainstream without losing her edges, the comic lead who delivered the most persuasive case for rom-com as high art in a decade of auteur seriousness, the dramatic lead who held her own in an epic about revolution, the director attuned to small domestic truths, the late-life movie star who made visibility and age feel compatible. That she inspired, steadied, and delighted Woody Allen is part of the public record and, today, part of the news. That she inspired millions of viewers to dress a little looser, to speak a little more honestly, and to believe that awkwardness can be a kind of elegance—that, too, is a matter of public record, written into the lasting pull of her films.

Allen’s essay, by his own description, is a private act shared with the public. It reads like a man acknowledging what the audience recognized decades ago: Diane Keaton set the tone. In that sense, it is not a shock. It is a thank-you note attached to a filmography. The laugh he hears in his head is the same one that rings through Annie Hall when the reality of love becomes too exquisite to bear straight. It is the laugh of someone who made complicated things feel simple for a moment. It is the laugh of a compass pointing toward true north, even when everyone else was dizzy.

Two days after her death, that is what he offered. The rest is ours to keep—on the screen, in the echoes, in the clothes we wear on a brave day, in the belief that kindness and originality can survive long careers and longer memories. If you need a final measure of her influence, consider this: the people who worked with her loved her and the people who watched her felt known by her. That is a rare thing. It is why the world feels smaller now, and why, as Allen wrote, her laugh remains.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load