At 80 years old, Pattie Boyd is finally telling her story in full—unvarnished, unfiltered, and heartbreakingly honest. For decades, she was the iconic muse behind some of rock’s greatest love songs, her beauty and presence immortalized in classics like George Harrison’s “Something” and Eric Clapton’s “Layla.” But the reality behind the lyrics and photographs was far more complicated than the world ever imagined. Now, with the wisdom and clarity gained from a lifetime spent in the shadow of fame, Boyd is peeling back the glamour to reveal the betrayal, humiliation, and pain that defined her most intimate relationships.

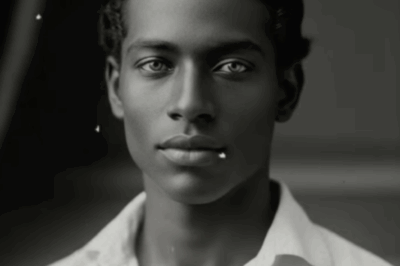

Boyd’s journey began far from the glitz of London’s rock scene. Born Patricia Anne Boyd in Somerset, England, she grew up as the eldest of four children in a family shaped by her father’s Royal Air Force service, a move to Nairobi, and the disruption of her parents’ divorce. The instability of her early years left her restless and searching for her place in the world. Her first job was as a shampoo girl at a local salon—a humble start that changed dramatically when a photographer’s assistant spotted her and launched her into the world of modeling. Soon, Boyd’s wide-eyed beauty and bohemian style graced the covers of Vogue, Elle, and Vanity Fair. Designers named collections after her, and her look helped define the swinging sixties.

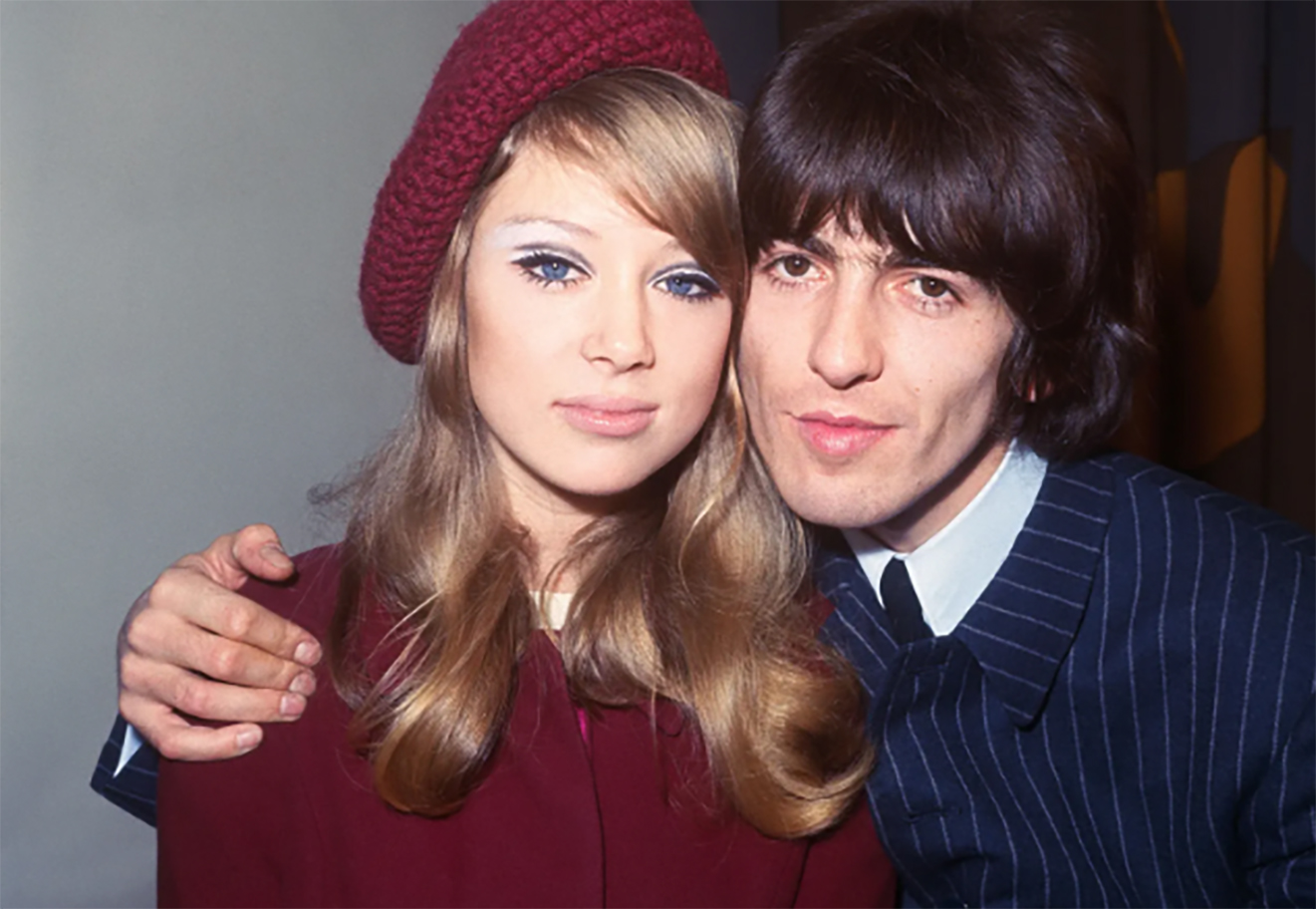

But it was a small role in the Beatles’ film “A Hard Day’s Night” that changed everything. On set, she met George Harrison, the band’s quiet, spiritual lead guitarist. Their attraction was immediate, and by 1966, Boyd and Harrison were married. Harrison adored her, writing timeless songs in her honor and famously inspiring Frank Sinatra to call “Something” the greatest love song of the last fifty years. Yet even in those early days, cracks were forming. Harrison’s growing obsession with Indian spirituality and his eventual infidelities left Boyd feeling isolated and unseen. At his request, she gave up modeling, hoping to strengthen their marriage, but instead found herself trapped in the role of a “little wife at home,” longing for affection and validation.

That longing would eventually draw her toward another man—George’s close friend, Eric Clapton. Clapton, already a legend in his own right, moved in the same elite circles of London’s rock and fashion scene. By the mid-1960s, he was carving out a reputation as one of the most gifted guitarists of his generation. He’d played with the Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Blues Breakers, earning the nickname “Slowhand.” In 1966, he co-founded Cream, whose heavy blues sound propelled him to global fame. But while his professional life soared, his personal life was tormented by a fixation he couldn’t shake. Despite his deep friendship with Harrison, Clapton had fallen hopelessly in love with Boyd. His feelings were no secret among his inner circle, and in 1969, his obsession spilled onto paper. Boyd received a letter from an anonymous admirer signed only with the initial “E”—a letter filled with desperation and longing, declaring he would sacrifice everything for her love. Years later, Boyd admitted the intensity of Clapton’s words shook her to the core. At the time, she chose loyalty, telling Harrison what was happening, but Clapton’s anguish only deepened.

His unrequited love eventually manifested in music, culminating in the 1970 masterpiece “Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs.” Inspired by the Persian tale of Layla and Majnun, Clapton channeled his suffering into “Layla,” a searing confession of passion and despair unmistakably directed at Boyd. For Clapton, it was both a cry for help and a declaration of love that the whole world could hear. Boyd later confessed that the song broke her resolve—the realization that she had inspired such passion and creativity was overwhelming. “The song got the better of me. I could resist no longer,” she admitted.

By the early 1970s, Boyd’s marriage to Harrison was unraveling under the weight of infidelity and spiritual distance. Harrison’s immersion in Eastern spirituality, once a source of connection, became a lifestyle that often excluded Boyd. He spent long stretches in India, devoted to meditation and the Hare Krishna movement, while she was left feeling increasingly sidelined. Adding to her isolation were Harrison’s affairs. Boyd described him as a “hot-blooded boy” who relished the attention of women drawn to his fame. Flirtations escalated into blatant infidelity, and the most devastating betrayal came when she discovered Harrison’s affair with Maureen Starkey, Ringo Starr’s wife. Boyd recalled the humiliation of finding Maureen at Friar Park, the Harrison estate, lying casually on a mattress while George dismissed her presence with indifference. It was the breaking point—a wound that would never fully heal.

Meanwhile, Clapton’s pursuit became increasingly direct. No longer content to suffer in silence, he confronted Harrison himself in 1970, bluntly declaring, “I have to tell you, man, I’m in love with your wife.” The tension between the two men seeped into their music, culminating in what actor John Hurt later described as a “guitar duel” at Friar Park—a charged jam session where Harrison and Clapton expressed their rivalry and frustration not with fists, but with their instruments. While Boyd insisted the event was exaggerated, she admitted the emotions were real. “They were boy men,” she said. Any annoyance, anger, and irritation from George only really came out when he was playing guitar with Eric.

By 1974, Boyd could no longer ignore reality. Her marriage to Harrison had become intolerable—a hollow shell eroded by neglect and betrayal. She left him that year, closing the chapter on nearly a decade as the wife of a Beatle. But freedom did not bring peace; it only ushered in a new and equally complicated storm. Waiting in the wings was Clapton, whose passion had not waned, but whose demons were about to consume them both.

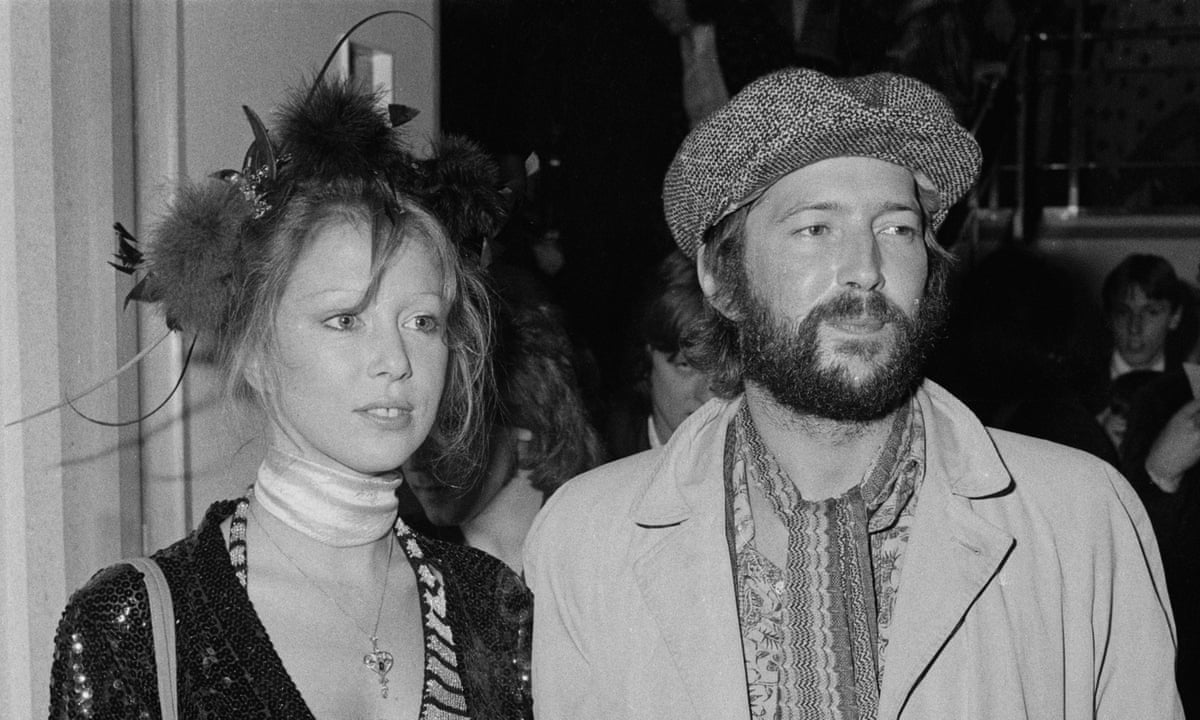

When Boyd finally separated from Harrison, it seemed inevitable that she and Clapton would become a couple. For years, he had pursued her relentlessly, pouring his obsession into music, letters, and public declarations. In 1977, after her divorce from Harrison was finalized, Boyd and Clapton began openly dating. Two years later, they married in Tucson, Arizona. Harrison even attended the wedding, jokingly referring to Clapton as “his husband.” To the outside world, this unusual arrangement symbolized a bond of friendship that survived betrayal. For a brief time, the marriage between Boyd and Clapton appeared to be a love story that had finally reached its climax.

But behind the smiles and appearances, the reality was far darker. Clapton was still in the throes of his battles with alcohol and drugs. Years of heroin addiction had left scars, and while he had managed to overcome that phase, alcoholism soon took its place. His drinking binges and erratic behavior poisoned the relationship. Boyd later revealed that his mood swings, fueled by substance abuse, left her living in a state of constant uncertainty. What should have been a stable and fulfilling marriage became another cage of emotional turmoil.

There were also other struggles that tested their union. Clapton longed to start a family, and Boyd desperately wanted to give him children. They turned to in vitro fertilization treatments, but each attempt ended in heartbreak. Boyd described the process as humiliating and emotionally exhausting, the repeated failures leaving her devastated. While she was enduring the silent grief of infertility, Clapton betrayed her trust in the most painful way possible. In 1985, Boyd discovered that Clapton had fathered a daughter, Ruth, with recording studio manager Yvonne Kelly. The betrayal cut deeply, especially since Boyd had been enduring the crushing disappointment of failed IVF treatments at the time. Just a year later, Clapton fathered another child, Conor, with Italian actress Lory Del Santo, while still married to Boyd. For Pattie, the discovery was like a dagger to the heart. She later admitted that she felt mocked by fate, struggling desperately to have children with the man she loved while he was fathering them with other women in secret.

By the mid-1980s, the marriage was collapsing under the weight of addiction, infidelity, and broken dreams. Boyd left Clapton in 1987, and their divorce was finalized in 1989. Looking back, she described the experience as devastating, admitting, “I had lost my sense of self. I was no longer Mrs. Famous George or Mrs. Famous Eric. Who was I? I was no one.”

When Boyd walked away from Clapton, she was more than just a woman leaving a marriage—she was someone struggling to rediscover who she really was after decades defined by others. For more than twenty years, she had lived in the shadows of two of the most celebrated musicians in the world. First as the wife of a Beatle, then as the muse of a guitar god. She had been praised, idolized, and sung about, yet rarely seen for herself. Now divorced from both, she was determined to reclaim her own identity.

Boyd turned to therapy to untangle the web of betrayal, neglect, and pain that had defined her relationships. She admitted openly that her sense of self-worth had been shattered. The constant comparison, first to the endless stream of women in Harrison’s life and later to Clapton’s infidelities, had left scars. But healing came slowly, and part of that healing was through creativity. Photography, which had once been a private passion, became her salvation. Boyd began documenting the world around her with a keen eye shaped by her years in the heart of rock and roll. Her photographs were intimate, authentic, and deeply personal, capturing moments not just of the famous figures she had known, but also her own journey of survival. Over time, her work gained recognition, and she began to emerge as an artist in her own right, no longer defined solely as a muse.

Writing became another form of liberation. In 2007, Boyd released her memoir, “Wonderful Tonight: George Harrison, Eric Clapton, and Me.” The book became an international bestseller, praised for its honesty and rawness. For the first time, she told the world what it had really been like to live with two of rock’s biggest icons—the infidelities, the loneliness, the pain, and the rare moments of genuine connection. Her candid revelations shocked fans who had long idealized her marriages. But the memoir was more than an exposé; it was her way of reclaiming her voice after decades of silence.

By the time she entered her seventies, Boyd had become comfortable living outside the shadow of rock mythology. In 2015, she married Rod Weston, a property developer she had known for years, in a quiet ceremony at Chelsea Old Town Hall. Unlike her earlier marriages, this one was not built on fame, obsession, or chaos. It was grounded in companionship, peace, and mutual respect. After a lifetime of being the woman behind the songs, Pattie Boyd finally began to write her own story.

Today, Boyd speaks with a clarity that only comes from surviving decades of pain, passion, and disillusionment. The glamour of being a rock muse has long since faded, replaced by the sobering truth of what those years really cost her. She has admitted that life with Eric Clapton was not the romantic dream the public imagined—it was a cycle of addiction, betrayal, and emotional neglect. The man who once declared he would sacrifice everything for her love ended up breaking her trust in the most intimate way. Boyd has not shied away from calling out the hypocrisy she endured. While she struggled with the heartbreak of failed IVF treatments and the crushing pressure of infertility, Clapton was fathering children with other women. She has described the discovery of his infidelities as a stab in the heart, a betrayal that felt all the more cruel because it mocked her deepest wounds.

Yet her revelations are not meant to inspire pity. They are acts of reclamation. Boyd has chosen to tell her story on her own terms, refusing to be remembered only as a face in someone else’s song. Through her memoir, exhibitions, and candid interviews, she has confronted the myths that once painted her life as glamorous. She has reminded the world that behind “Layla” and “Wonderful Tonight” was a woman enduring heartbreak, humiliation, and loneliness. And yet there is also resilience in her legacy. Despite the betrayals and disappointments, Boyd has rebuilt her life. She has found stability with her third husband, Rod Weston, and continues to be celebrated for her photography and cultural influence. At 80, she stands not as a muse defined by others, but as a survivor who has finally revealed the truth—unfiltered, painful, and necessary.

News

After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer walked into my office and smugly handed me divorce papers, saying, “She’ll be taking everything—the house, the cars, and full custody. Your kids don’t even want your last name anymore.” I didn’t react, just smiled and slid a sealed envelope across the desk and said, “Give this to your client.” By that evening, my phone was blowing up—her mother was screaming on the line, “How did you find out about that secret she’s been hiding for thirteen years?!”

Checkmate: The Architect of Vengeance After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer served me papers at work. “She gets…

We were at the restaurant when my sister announced, “Hailey, get another table. This one’s only for real family, not adopted girls.” Everyone at the table laughed. Then the waiter dropped a $3,270 bill in front of me—for their whole dinner. I just smiled, took a sip, and paid without a word. But then I heard someone say, “Hold on just a moment…”

Ariana was already talking about their upcoming vacation to Tuscany. Nobody asked if I wanted to come. They never did….

The Impossible Mystery Of The Most Beautiful Male Slave Ever Traded in Memphis – 1851

Memphis, Tennessee. December 1851. On a rain-soaked auction block near the Mississippi River, something happened that would haunt the city’s…

The Dalton Girls Were Found in 1963 — What They Admitted No One Believed

They found the Dalton girls on a Tuesday morning in late September 1963. The sun hadn’t yet burned away the…

“Why Does the Master Look Like Me, Mother?” — The Slave Boy’s Question That Exposed Everything, 1850

In the blistering heat of Wilcox County, Alabama, 1850, the cotton fields stretched as far as the eye could see,…

As I raised the knife to cut the wedding cake, my sister hugged me tightly and whispered, “Do it. Now.”

On my wedding day, the past came knocking with a force I never expected. Olivia, my ex-wife, walked into the…

End of content

No more pages to load