The first time I met Theodore Wright, Harlem’s finest criminal defense attorney, it was 1952 and the city was humming with secrets. He wore a tailored suit and a smile that could charm a judge, but I knew better than to trust anyone who made a living talking for money. Still, over the years, Wright became my shield in the courts—a man who understood the difference between justice and survival. I paid him in cash, always on time, and he kept me out of jail more times than I could count.

By April of 1963, that relationship was about to change forever.

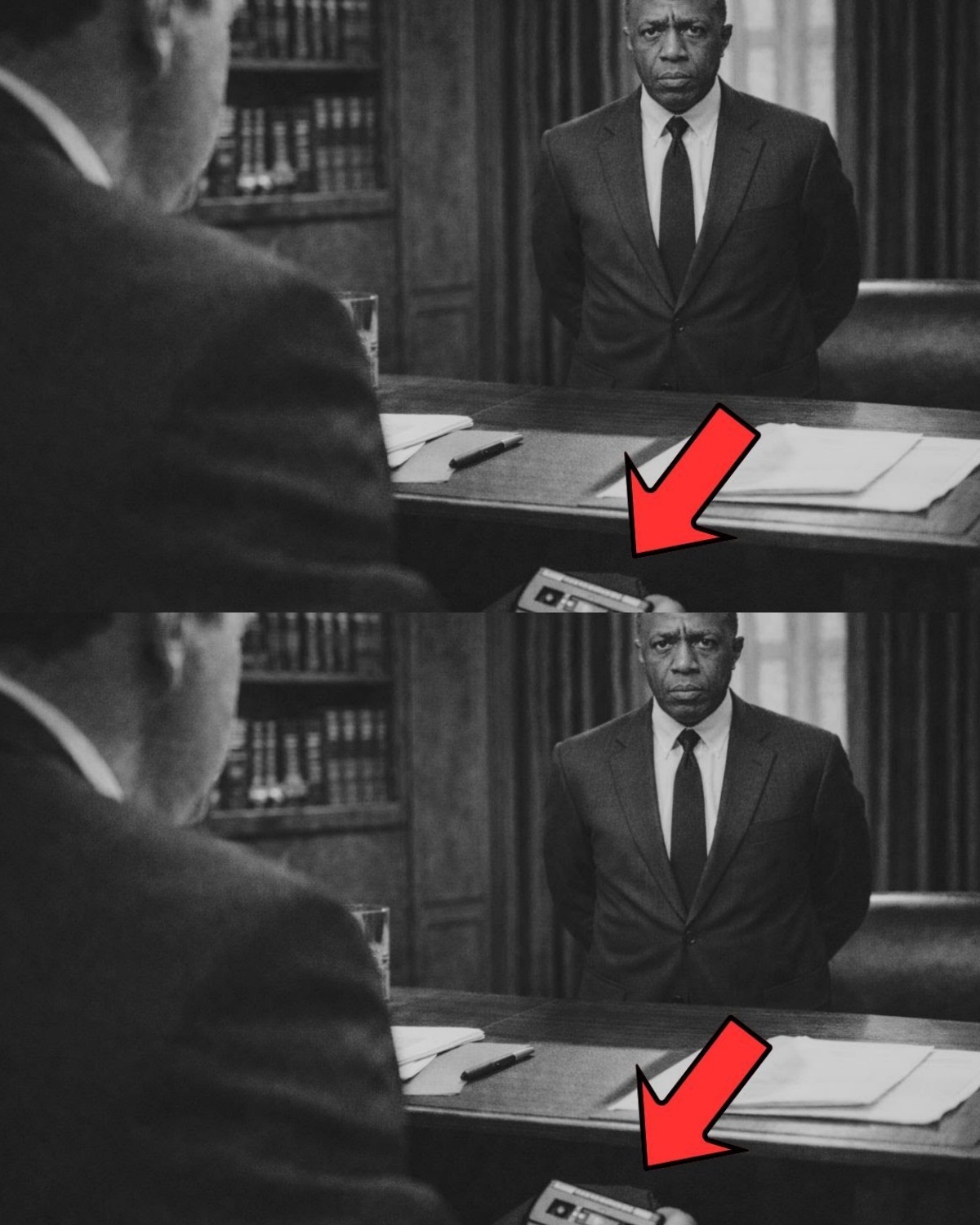

It was a Tuesday, the kind of cold, gray afternoon where the city’s shadows seemed deeper than usual. I walked up the stairs to Wright’s office on 125th Street, third floor, conference room with the mahogany table and leather chairs. I’d been summoned for a “routine consultation” about an upcoming trial. Routine, Wright called it. I knew better. Routine in my world meant someone was about to betray you, and you’d better be ready.

I paused outside the door, listening to the muffled voices inside. Lawyers always thought they were the smartest men in the room. But I’d survived forty years in Harlem because I never underestimated anyone. I’d learned to listen—not just to words, but to the silences between them.

When Wright greeted me, his handshake was firm, his eyes steady. But there was a flicker—just for a second. Nervousness. I’d seen it before, in men who owed me money or in cops who knew they were about to cross a line. Wright motioned for me to sit. I took my usual seat, the one facing the window, where I could see the street and anyone approaching.

He started with small talk, but I could feel the tension underneath. He was fishing for details, asking about my operations, my contacts, my arrangements with other families. I answered, careful as always. But I knew something he didn’t.

Two weeks earlier, one of my sources—a clerk in the FBI’s New York office—had tipped me off. She worked in the clerical pool, shuffling papers, filing expense reports. She’d seen Wright’s name in surveillance documents, payments from the Bureau for “confidential information regarding organized crime.” The address matched Wright’s office. She didn’t know the details, but she knew enough. I paid her well for that knowledge. It was worth every dollar.

I’d spent those two weeks deciding how to play it. The easy answer would have been violence. Confront Wright, threaten him, maybe kill him. But I’d learned that killing a man only solved the immediate problem. It never fixed the system that created the betrayal. Besides, violence draws attention. I preferred to win quietly.

So I made a plan. I’d keep meeting with Wright, keep talking, but every word would be a weapon. I’d feed him information—controlled, deliberate, designed to mislead the FBI and protect my real operations. If Wright wanted to record me, I’d give him a performance he’d never forget.

That day, as I settled into the leather chair, I saw Wright reach for his briefcase. He thought he was slick, but I could hear the faint click of a recorder activating. I smiled inwardly. The game was on.

“Thodor,” I said, using the old nickname, “I want to talk to you about everything. Everything I’m involved in, everything I’m planning, everything the FBI might want to know. I want it all on the record in case anything happens to me.”

Wright’s eyes widened. He thought I was confessing, maybe facing mortality, maybe wanting to clear my conscience. He encouraged me, asked questions, prompted me to elaborate. So I talked. For three hours straight.

I described gambling operations—named locations, provided revenue numbers, explained organizational structures. I talked about political corruption, named officials on my payroll, described bribes paid to specific people on specific dates. I detailed arrangements with mafia families, explained territorial divisions, described meetings with organized crime figures. I confessed to criminal activities, admitted to running illegal operations, acknowledged breaking laws.

But here’s the thing: sixty percent of what I said was pure fiction. I invented gambling houses at addresses where no gambling occurred, named employees who didn’t exist, provided revenue figures that were wildly inflated. I attributed quotes to officials who’d never met me, described bribes that never happened, created elaborate fictions about corruption that would lead the FBI on wild goose chases for months.

Thirty percent was technically true but useless for prosecution. Details the FBI already had, vague admissions, careful language that sounded incriminating but wouldn’t hold up in court. I admitted to involvement in gambling without specifying my exact role, acknowledged awareness of criminal activities without claiming direct participation.

The remaining ten percent—the dangerous part—was true and designed to expose other FBI informants. I described criminal activities with details only certain people could have known, details that had been reported to the FBI by confidential sources. By including these, I was telling the FBI, “I know you have informants, and I know what they’ve told you.”

The genius was in the details. Small inconsistencies, minor contradictions, deliberate errors. I’d describe an event in detail, then later in the conversation, describe the same event with slightly different details. Different dates, different locations, different people present. Subtle enough not to jump out, but embedded throughout, waiting to be discovered by any defense attorney who listened closely.

The recorder ran for three hours and seven minutes. When Wright finally turned it off, he looked exhausted. He thought he had a gold mine—a major criminal target confessing to crimes, naming co-conspirators, describing illegal operations in meticulous detail. He couldn’t wait to hand it over to his FBI handler.

Within 48 hours, the recording reached the Bureau. Agents listened, transcribed, analyzed. At first, they were thrilled. This was the evidence they needed to build a case, maybe put me away for good. But as they started investigating the claims, problems emerged.

Gambling operations at the addresses I’d given didn’t exist. Surveillance revealed legitimate businesses or residential buildings. Political officials I claimed to have bribed denied any contact. Revenue figures didn’t match financial intelligence. The numbers were too high, too round, too convenient.

By late April, the FBI began to suspect something was wrong. A memo dated April 29th expressed concern: “Subject’s statements to attorney appear to contain significant fabrications. Unclear if subject is delusional, deliberately misleading counsel, or aware of recording and providing disinformation. Recommend increased caution in relying on this source.”

But the Bureau didn’t want to admit they’d been deceived. Institutional inertia kept them chasing leads, wasting resources, relying on Wright’s recordings for months. Meanwhile, I kept meeting with Wright, kept talking, kept feeding the recording device a carefully crafted mixture of lies, half-truths, and misdirection.

I found the whole thing darkly amusing. I’d created a three-hour recording that should have incriminated me, but instead was destroying the FBI’s investigation and compromising their other informants. I’d turned my lawyer’s betrayal into a weapon against my enemies, and all I’d done was talk.

By November, the FBI finally concluded Wright’s recordings were compromised. “Subject Johnson appears to have knowledge of recording operations. Information provided through this source should be considered compromised and unreliable. Recommend termination of relationship with source and consideration of alternative investigative approaches.”

Wright was informed his cooperation was no longer needed. The FBI stopped meeting with him, stopped paying him, abandoned him. But his problems were just beginning.

Word spread in Harlem’s legal community that Wright had been cooperating with the FBI, recording clients, violating attorney-client privilege for money. The rumors were specific, detailed, and damaging. The source was never identified, but the timing suggested it came from someone who knew exactly what Wright had done—someone like me.

By early 1965, the New York State Bar Association opened an investigation. They found Wright had indeed been recording client conversations and providing them to law enforcement without client knowledge or consent. Disbarment was inevitable. Wright lost his law license, his practice, his reputation. He tried to rebuild, working as a paralegal, but never recovered.

In a 1972 interview, Wright spoke publicly about his cooperation with the FBI. “I thought I was being smart, thought I was gathering evidence, thought I had the upper hand because I was secretly recording, but Bumpy knew from the very beginning of that April meeting. He knew, and he used my own recording device to destroy me.”

The interviewer asked how he knew I’d been aware of the recording. Wright’s response was telling: “Because everything he said was too perfect, too detailed, too comprehensive. Nobody talks that way naturally. Nobody confesses that thoroughly without being prompted. He was performing and I was too stupid or too greedy to realize it.”

He regretted cooperating with the FBI every day. “I betrayed a client, violated everything lawyers are supposed to stand for, and I got nothing for it except professional destruction. The FBI used me and discarded me. And Bumpy, Bumpy turned my betrayal into his weapon, made me the fool, and himself the genius. I helped him by trying to hurt him.”

But Wright never understood the real lesson. A recording device doesn’t capture truth. It captures whatever the person being recorded chooses to say. If that person knows they’re being recorded, they control the narrative completely. Wright thought the recording device gave him power. I knew that knowing about the recording gave me greater power—the power to control what was documented, to feed false information to my enemies, to turn surveillance into a disinformation weapon.

The three-hour monologue wasn’t a confession. It was theater, designed to waste FBI resources, expose their informants, compromise their investigation, and destroy the credibility of their primary source. It worked perfectly.

Surveillance only provides advantage if the subject doesn’t know they’re being monitored. Once someone knows, they control the information. Volume doesn’t equal quality. The FBI got hours of recordings, but quantity didn’t translate to usefulness. False information, properly crafted, can be more damaging than silence. If I’d stopped talking to Wright, the FBI would have known something was wrong. By continuing to talk but feeding them lies, I kept them invested in a compromised source, leading them down dead ends.

Bureaucracies resist acknowledging failure. Even when evidence mounted that Wright’s recordings were unreliable, the FBI continued using them for months. Admitting the source was compromised meant admitting their approach was flawed.

These principles—knowledge of surveillance neutralizes surveillance, false information can be weaponized, bureaucracies resist failure—showed strategic sophistication far beyond what most attributed to street criminals in 1963. But I wasn’t most criminals. I’d survived hostile environments for forty years by being smarter than the people trying to catch me.

I never publicly discussed the Wright situation, never confirmed I’d known about the surveillance, never took credit for the disinformation campaign. But people close to me knew. I told my wife about discovering Wright’s betrayal and my decision to keep talking, told her I’d spent three hours feeding the FBI enough rope to hang themselves. I was quietly proud of how I’d handled it. It was one of my more elegant victories—winning without violence, destroying an enemy’s credibility rather than destroying the enemy physically.

A former associate said it best: “Bumpy could have killed Wright, could have made him disappear, but that would have just created another informant problem. Instead, Bumpy destroyed Wright’s usefulness as an informant, and his career as a lawyer. Made him worthless to the FBI and unable to practice law, more permanent than death in some ways.”

Death would have solved the immediate problem, but created new ones—FBI investigation, possible retaliation, loss of information about what the FBI knew. Destroying Wright’s credibility and career solved the problem more thoroughly. Wright couldn’t provide useful information. The FBI couldn’t trust anything he’d provided. Wright lost everything, and I never had to resort to violence.

When I died in July 1968, Wright was living in a small apartment in Queens, working as a paralegal, disbarred and disgraced. He died bitter, convinced I’d destroyed him. He never understood that his own betrayal had created the situation, that violating attorney-client privilege had set in motion the events that ruined him. He saw himself as a victim of my cleverness, never acknowledging he’d been a perpetrator first.

April 9th, 1963, 2:47 p.m. Third floor conference room, 125th Street. I sat down across from my lawyer, knowing every word would be recorded, knowing the FBI would analyze every sentence, knowing I was being betrayed by someone I’d trusted and paid. And I talked for three hours, delivered a masterclass in disinformation, created a recording that seemed incriminating but was actually a weapon, fed the FBI false information that wasted their resources and compromised their investigation.

I turned my lawyer’s betrayal into my own advantage. Turned a recording device meant to capture me into a tool to destroy my enemy’s credibility. No violence, no threats, just words—carefully chosen words designed to mislead, confuse, and ultimately triumph.

That’s power. Not the power of fear or force, but the power of intelligence and strategy. The power of understanding that information is a weapon, and that controlling what your enemies hear is more effective than preventing them from hearing anything.

Theodore Wright thought he was gathering evidence. He was destroying his own credibility and career. The FBI thought they were conducting surveillance. They were receiving disinformation that compromised their entire investigation. And me, seemingly at a disadvantage, being recorded without my knowledge, turned that into victory by talking—just talking for three hours about things that weren’t true to a man who thought he was being clever, for an audience that thought they were gathering evidence.

All of them were wrong. And I knew it from the very first word.

Sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is keep talking when everyone expects you to shut up. If you control what you say, if you understand your audience, if you recognize that words can be weapons more effective than bullets, then talking becomes warfare. And I won that war without firing a shot—just by talking for three hours about things that weren’t true, to a man who thought he was gathering evidence, for an audience that thought they were building a case.

They were all wrong. And I was right.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load