Nearly five decades after its release, Close Encounters of the Third Kind still feels like a transmission from another world. But the story behind this sci-fi classic is stranger—and more inspiring—than any Hollywood alien invasion. From a director’s spiritual gamble to cast members’ transformative experiences and a studio system that nearly buried the film, the real making of Close Encounters is a saga of risk, awe, and cinematic rebellion.

Hollywood’s Most Spiritual Sci-Fi Almost Never Happened

When Steven Spielberg pitched his vision for Close Encounters, Hollywood was in no mood for enlightenment. The 1970s studio system thrived on fear—alien movies meant destruction, not communion. Spielberg’s pitch? Aliens as peaceful, enlightened visitors, not monsters. Every major studio passed, unable to grasp a story without explosions or invaders. Only Columbia Pictures, still riding high from Spielberg’s Jaws, reluctantly greenlit the project—betting on the director, not the idea.

Pressure mounted from day one. Studio execs demanded action, spectacle, and a clear enemy. “They kept asking, ‘Where’s the explosion? Where’s the enemy?’” recalled Richard Dreyfuss, who played everyman Roy Neary. Teri Garr, cast as Roy’s wife, saw the script rewritten repeatedly as the studio tried to force in more traditional alien invasion tropes. But Spielberg fought back, rewriting drafts to keep the focus on wonder, curiosity, and emotional transformation. He wanted a story about connection, not conquest—and he refused to budge.

A Sacred Mountain, a Sacred Message

If the story was a gamble, the location was a revelation. Spielberg chose Wyoming’s Devil’s Tower—a sacred site for Native American tribes—as the film’s centerpiece. For centuries, the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Kiowa have regarded the tower as a bridge between worlds. Spielberg, sensitive to this history, saw it as the perfect symbol for humanity’s leap into the unknown.

For the cast, filming at Devil’s Tower was transformative. “You stood beneath it and believed aliens could come here,” Dreyfuss said. Melinda Dillon, who played Jillian Guiler, called the shoot “spiritually grounding,” describing the experience as filming “at a cathedral built by the Earth.” The location didn’t just serve the story—it shaped it, infusing every scene with awe and humility.

A Mother Ship Like No Other

Few images in film are as iconic as the glowing mother ship’s descent. But behind the scenes, the ship was a four-foot miniature, brought to life with thousands of hand-programmed lights and live, on-set effects. The cast didn’t react to green screens or placeholders—they experienced a real, dazzling light-and-music show. “It felt like being inside a living machine,” Teri Garr remembered.

Spielberg’s insistence on practical effects paid off. The mother ship felt alive, its gentle curves and soft lights designed to inspire, not intimidate. French New Wave legend François Truffaut, cast as scientist Claude Lacombe, likened the ship’s arrival to a sacred visitation. The result was a science fiction spectacle that felt less like an invasion and more like a miracle.

Richard Dreyfuss: Method Acting on the Edge

To play Roy Neary, Dreyfuss dove deep into the psychology of obsession. He isolated himself from friends and family, interviewed “alien encounter” survivors, and studied trauma and compulsive behavior. The iconic mashed potato scene—where Roy sculpts Devil’s Tower at the dinner table—was improvised, based on real accounts of people trying to make sense of the incomprehensible. Dreyfuss’s intensity blurred the line between actor and character, unsettling the cast and adding raw authenticity to every scene. “He wasn’t acting,” said one crew member. “He was manifesting trauma.”

François Truffaut: The Art Film Soul of a Blockbuster

Casting François Truffaut was a radical move. Truffaut, a legendary director but not a Hollywood actor, brought a gentle, inquisitive presence to the film. Spielberg directed him through emotional cues, not traditional lines, and Truffaut responded with a performance that grounded the film in sincerity. As Lacombe, he was the scientist who sought understanding, not control—a living embodiment of the film’s message that the unknown should be met with curiosity, not fear.

Truffaut’s influence went beyond acting. He collaborated with Spielberg on set, offering creative input and helping shape the film’s philosophical tone. His presence gave Close Encounters a distinctly European sensibility—less about spectacle, more about the search for meaning.

The Five-Note Melody That Changed Sci-Fi

No element of Close Encounters has endured like its haunting five-note melody. Composer John Williams, working closely with Spielberg, designed the motif as a plausible, universal language—one that could theoretically be recognized by any intelligent life. Williams researched mathematical relationships between tones, seeking a sequence that embodied curiosity and peace. The melody became the film’s emotional heartbeat, drawing Roy—and the audience—toward the unknown.

On set, the musical exchange between humans and aliens was performed live, with actors reacting to real lights and sounds. Truffaut later said, “We weren’t just acting. We were participating in a real musical conversation.” The result was a scene of genuine awe, a cinematic communion that redefined what science fiction could be.

A Government Conspiracy That Felt Too Real

While Close Encounters is remembered for its optimism, a thread of government secrecy runs through the film. Spielberg consulted with military advisors and UFO researchers to create realistic depictions of cover-ups and misinformation. In post-Watergate America, the idea of a government hiding the truth about aliens felt not just plausible, but timely. “People were ready to believe the government would lie about aliens. They already thought they were lying about everything else,” Dreyfuss reflected.

The film’s release tapped into a national mood of suspicion—and some officials reportedly worried about its impact on public trust. Yet Spielberg’s story didn’t stop at paranoia. In the end, it was an ordinary man, not the government or the military, who stepped forward into the unknown.

A Film About Faith, Not Fear

Close Encounters of the Third Kind isn’t just about aliens. It’s about wonder, faith, and the human longing for connection. From sacred landscapes to method acting breakdowns, from government conspiracies to the universal language of music, the film’s creation was a journey as mysterious and profound as the story it tells.

So, what really happened behind the scenes of this cinematic enigma? The answer is simple: Spielberg and his cast refused to settle for fear, cynicism, or convention. And in doing so, they created a film that still feels like a message from somewhere beyond.

Did this change how you see Close Encounters? Let us know in the comments—and stay tuned for more untold stories from the frontiers of film.

News

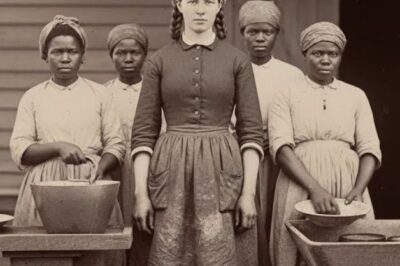

She Was ‘Unmarriageable’ — Her Father Sent Her to Work With the Slaves, Alabama 1854

In the red clay hills of Jefferson County, Alabama, the summer of 1854 arrived heavy as a shroud, carrying with…

On Christmas Eve, my parents kicked me out with nothing but a suitcase. My sister sneered, “Good luck surviving.” Freezing on a snowy bench, I saw a barefoot woman turning purple and gave her my boots. An hour later, 19 black BMWs pulled up around me… and the woman stepped out with a single chilling sentence.

On Christmas Eve, the heavy oak doors of my parents’ mansion in Hillsborough didn’t just open; they expelled me. My father, Richard, threw…

After the divorce, my ex left me with nothing. With nowhere else to turn, I dug out the old card my father had once given me and passed it to the banker. The moment she looked at her screen, she went rigid, her expression shifting sharply. “Ma’am… you need to see this right now,” she said. What she revealed next left me completely speechless…

I never expected the end of my marriage to look like this—standing inside a small branch of First Horizon Bank…

FAMILY ‘TURMOIL’ — Anna Kepner’s Final Moments Revealed

FAMILY ‘TURMOIL’ — Anna Kepner’s Final Moments Revealed Tragic new details emerge about Anna Kepner’s last moments on the Carnival…

Drew Pritchard FINALLY Names The 5 Worst Members On Salvage Hunters

In the quiet corners of British countryside, where the scent of rain lingers on stone and the hum of traffic…

“You’ve been living here for three months already! And haven’t given a single penny!” – my husband’s sister and her husband decided to sit on my neck.

Natalya was wiping dust off the coffee table when she heard a familiar crunch. She lifted her head and froze….

End of content

No more pages to load