In the restless spring of 1829, northern Georgia was a place on the edge of transformation. The first glimmers of gold had begun to draw fortune seekers from across the young nation, their dreams and desperation reshaping the hills and valleys with each passing day. But as the Georgia Gold Rush erupted, the land did not yield only treasure—it unearthed secrets, some so unsettling that even those who uncovered them struggled to comprehend their meaning. Among these was the forbidden story of Celeste, a beautiful woman whose image, preserved against all odds, would become the key to a mystery that still lingers in the shadows of American history.

The legend of Celeste begins not with gold, but with a photograph—a portrait that should never have existed. In 1829, daguerreotype technology was rare and costly, reserved for the wealthy and powerful. Most enslaved people lived and died without their faces ever captured by a lens. Yet, hidden deep in the mountains of Habersham County, a single photograph survived. It was discovered in 1963, during the renovation of the long-abandoned Whitmore estate, tucked away in a small wooden box sealed with wax and wrapped in oiled cloth. Inside the box were three items: the photograph, a lock of dark hair tied with blue ribbon, and a letter written in a delicate, careful hand.

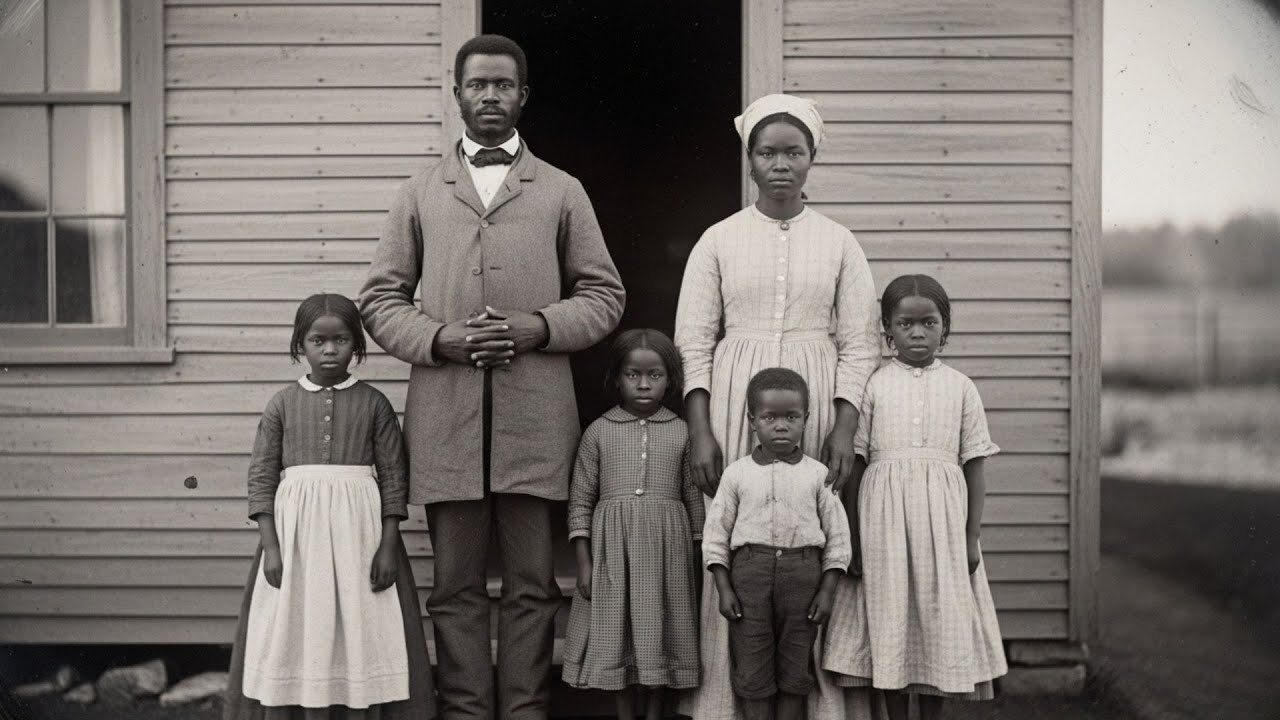

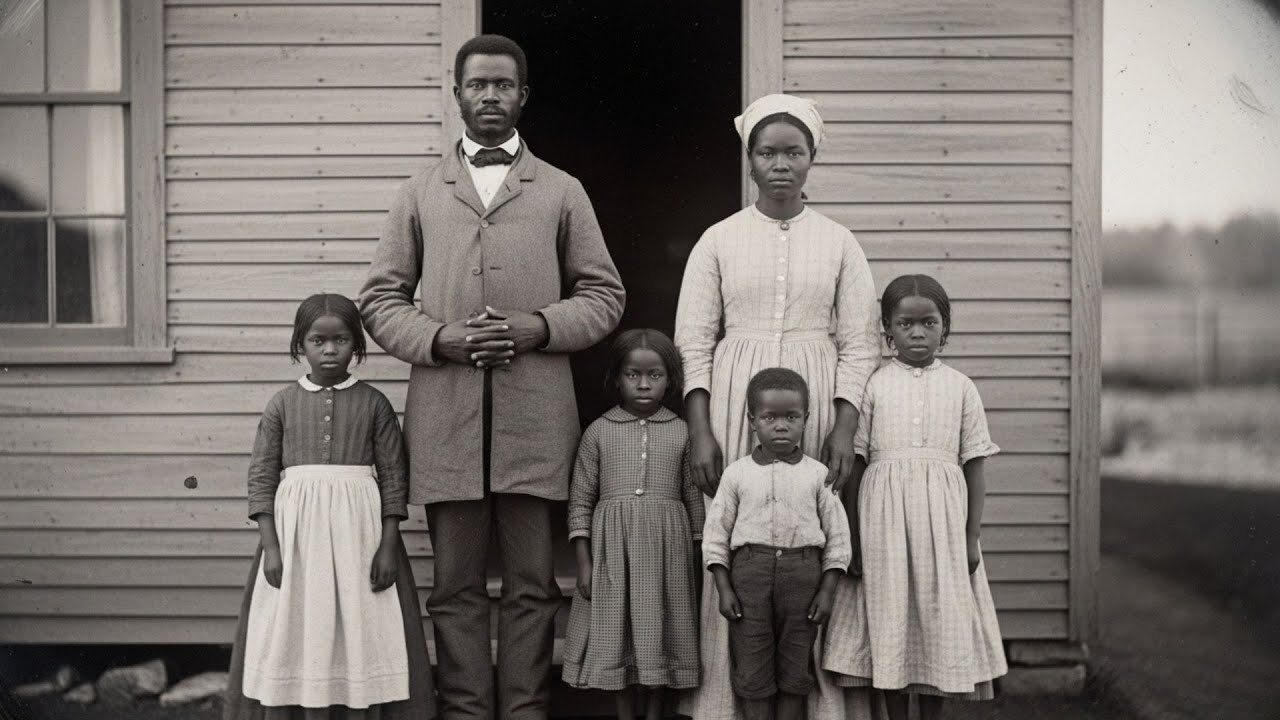

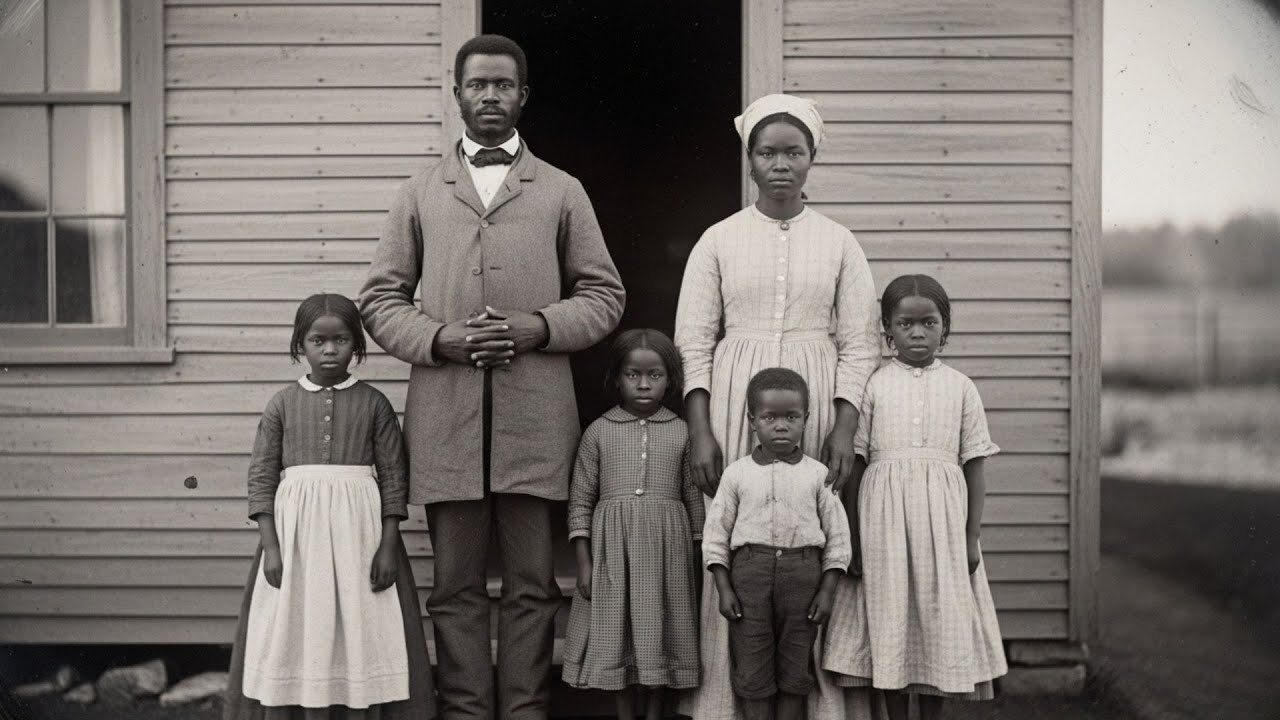

The image was haunting. Celeste sat beside a polished wooden table in a parlor that spoke of wealth and refinement, her dress a shimmering silk rather than the coarse homespun of the enslaved. Her hands were folded in her lap, her gaze meeting the camera with a directness that was both gentle and defiant. On the back, an inscription read: “My dearest Celeste, may this image preserve what words cannot express. WH 1829.” The initials belonged to William Harrison Whitmore, the enigmatic owner of the estate—a man whose life, like the photograph, was marked by secrecy and contradiction.

William Whitmore had inherited the plantation in 1827, after two years spent in Philadelphia. Unlike his peers, he had studied chemistry and the emerging science of photography, ordering silver plates and chemicals from suppliers in Charleston and Savannah. His letters, discovered decades later in courthouse archives, revealed a fascination with technology that was unusual for a Georgia planter. The Whitmore estate itself was one of the largest in the region, its fields tended by over forty enslaved people. Yet even among the planter class, William was regarded as a recluse, more interested in strange experiments than in the social rituals of southern life.

The gold rush changed everything. Prospectors flooded into the region, their presence upending the fragile order of plantation society. Cherokee lands were overrun, treaties ignored, and violence simmered beneath the surface. In this chaos, the Whitmore plantation grew increasingly isolated. Visitors were discouraged, and William was rarely seen at church or the courthouse. His overseer, Thomas Garrett, complained that William had become secretive and unpredictable, often countermanding orders and making inexplicable changes to the daily routine.

It was during this tumultuous period that Celeste appeared in the records—a bill of sale dated March 15, 1829, showing that William had purchased a 20-year-old woman from a dealer in Augusta for the extraordinary sum of $400. The price suggested exceptional skills or unusual circumstances, but the records gave no details. Local rumor filled the gap. Some said Celeste was the daughter of a free woman of color, others that she had been brought to serve as a companion to William’s ailing mother. Yet no such woman lived on the plantation, and Celeste herself was never mentioned in the official ledgers again.

As summer approached, tension grew. Gold prospectors clashed with landowners, and the Cherokee faced mounting pressure to abandon their ancestral home. The Whitmore estate, once bustling, became eerily quiet. Workers cleaning out storage buildings found evidence of a makeshift photographic laboratory—glass plates, chemical baths, and equipment far beyond what would be expected in rural Georgia. The sophistication of the setup suggested that someone had been conducting serious experiments, perhaps in secret.

More disturbing were the reports from neighboring plantations. Travelers spoke of music drifting through the woods at night—melodies unfamiliar and instruments they could not identify. Lanterns flickered between the main house and Duke’s Creek, carried by figures who vanished when approached. Voices, sometimes in Cherokee and sometimes in languages unknown, echoed through the trees. The enslaved workers grew anxious, some attempting to run away despite the risk of brutal punishment. Overseers came and went, each leaving after only weeks, claiming nervous exhaustion or refusing to speak of their experiences.

The relationship between William and Celeste, whatever its true nature, was conducted in secrecy. The letter found with the photograph spoke of clandestine meetings by the creek, promises made in sacred places, and a love that existed outside the boundaries of law and society. The language was intimate and reverent, suggesting a bond that defied the conventions of the time. Yet, as historian Margaret Thornton later noted, the power imbalance inherent in slavery made any appearance of consent deeply suspect.

In October, the first sign of crisis emerged. Robert Caldwell, a neighboring planter, arrived to discuss livestock and found the main house deserted, save for an elderly enslaved man who claimed William was away on business. The enslaved community was fearful, the quarters half-empty, and those who remained gave contradictory accounts of their master’s whereabouts. Caldwell reported his concerns to Sheriff Daniel Morrison, but the investigation was perfunctory. Morrison, himself involved in gold mining, had little interest in matters that did not affect his own fortunes.

With William absent and no overseer in place, the enslaved people were left to fend for themselves. Some escaped, while others remained, hoping for leniency. During this period, workers discovered personal items belonging to Celeste—silk dresses, jewelry, and books inscribed with her name. The books, volumes of poetry and philosophy, were far beyond what any enslaved person would normally possess. The cabin where Celeste lived was unusually well-appointed, with glass windows and fine furnishings, more like the home of a woman of status than a slave.

Winter arrived early and harsh. Prospectors died of exposure, and the plantation’s enslaved population suffered from malnutrition and disease. By spring, the Cherokee—displaced from their own homes—reported seeing strange lights and hearing music from a burned cabin near Duke’s Creek. When they investigated, they found the remains of photographic equipment, women’s clothing, and what appeared to be human bones. Fearing blame, the Cherokee reburied the remains and kept silent.

As creditors and tax collectors descended on the Whitmore estate, a court-appointed administrator, Charles Hamilton, was tasked with inventorying the property. He found the population had dwindled, with no trace of Celeste. The photographic equipment was appraised and found to be far more advanced than anything used locally. Hamilton’s most disturbing discovery came when he uncovered a hidden chamber beneath the kitchen, filled with carefully wrapped photographic plates. The images, he later wrote, “defied both description and comprehension,” and much of his report was sealed, redacted, or destroyed.

The plantation was eventually sold at auction to a mining consortium, its enslaved people dispersed to other counties. The main house stood empty, its secrets buried until the 1960s, when the photograph and letter were found. Margaret Thornton spent years piecing together the story, interviewing elderly residents and consulting experts. Her conclusion was that the relationship between William and Celeste represented one of the most complex and disturbing cases of exploitation and manipulation in American slavery. The luxury and education afforded to Celeste, Thornton argued, were tools of psychological control, masking the fundamental violence of her situation.

The fate of the other photographic plates remains unknown; they were taken by court order and presumably destroyed. Theories abound—some believe William and Celeste escaped north or to Europe, others that they were murdered by prospectors. The most persistent account, supported by the Cherokee, is that both died in the fire that destroyed their secret cabin. No scientific examination was ever possible.

The broader implications of the case reach beyond the mystery of what happened to William and Celeste. Their story illustrates the contradictions of human relationships under slavery—where affection and exploitation, dignity and degradation, could coexist in impossible tension. The photograph, with Celeste’s direct gaze and dignified bearing, challenges viewers to recognize her humanity, even as it reminds us of the violence and inequality that shaped her world.

Modern analysis has revealed details previously unseen—a wedding ring on Celeste’s hand, silk and lace in her dress, and a level of sophistication that defied the stereotypes of slavery. DNA analysis of the hair sample has provided insights into her ancestry, though definitive identification remains elusive. The artifacts found at the site—books, jewelry, and photographic equipment—suggest a life of learning and refinement, but one lived in constant danger and secrecy.

The gold rush context is crucial. The chaos and lawlessness of the era allowed individuals like William to pursue forbidden desires, unchecked by community oversight. The breakdown of traditional authority created opportunities for exploitation, but also for resistance and escape. The isolation of the Whitmore plantation enabled secrecy, but also left Celeste with no means of protection or appeal.

The psychological dimensions of the case continue to fascinate scholars. Was Celeste a victim of intimate terrorism, her luxury and education used to create dependency and discourage resistance? Or did she find ways to assert her own dignity, even within the constraints of bondage? The truth is likely lost to history, buried with the remains near Duke’s Creek.

The legacy of the Whitmore case endures in the fragments that survive—a photograph, a letter, and the memories of those who lived through those turbulent years. The image of Celeste stands as a testament to the complexity of human experience under oppression. Her story is not easily categorized; it is at once a love story and a record of exploitation, a tale of resistance and a document of suffering.

As the years pass and new technologies emerge, researchers continue to search for answers. Ground-penetrating radar and advanced forensic techniques may one day uncover more evidence, but the passage of time makes resolution increasingly unlikely. The people who might have spoken are gone, their memories scattered and distorted by fear and shame.

What remains is Celeste’s image—a face that demands recognition, a gaze that refuses to be forgotten. Her story, preserved against all odds, reminds us that history is never simple. It is a tapestry of hope and heartbreak, dignity and degradation, love and loss. In the silence that surrounds the final fate of those who lived and died at the forgotten plantation, we find the truest testimony to the human cost of a system that sought to reduce people to property, yet could never fully extinguish the bonds of affection, hope, and determination that make us human.

In the end, the mystery of Celeste and William is less about solving a crime than about understanding the depth of human complexity in a world defined by injustice. Their story challenges us to look beyond the surface, to see the humanity that persists even in the darkest corners of history. And as long as her image endures, so too does the hope that we might one day learn to tell these stories with the compassion and honesty they deserve.

News

At my son’s wedding, he shouted, ‘Get out, mom! My fiancée doesn’t want you here.’ I walked away in silence, holding back the storm. The next morning, he called, ‘Mom, I need the ranch keys.’ I took a deep breath… and told him four words he’ll never forget.

The church was filled with soft music, white roses, and quiet whispers. I sat in the third row, hands folded…

Human connection revealed through 300 letters between a 15-year-old killer and the victim’s nephew.

April asked her younger sister, Denise, to come along and slipped an extra kitchen knife into her jacket pocket. Paula…

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

On my wedding day, my in-laws mocked my dad in front of 500 people. they said, “that’s not a father — that’s trash.” my fiancée laughed. I stood up and called off the wedding. my dad looked at me and said, “son… I’m a billionaire.” my entire life changed forever

The ballroom glittered with crystal chandeliers and gold-trimmed chairs, packed with nearly five hundred guests—business associates, distant relatives, and socialites…

“You were born to heal, not to harm.” The judge’s icy words in court left Dr. Michael McKee—on trial for the murder of the Tepes family—utterly devastated

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

The adulterer’s fishing trip in the stormy weather.

In the warehouse Scott rented to store the boat, police found a round plastic bucket containing a concrete block with…

End of content

No more pages to load