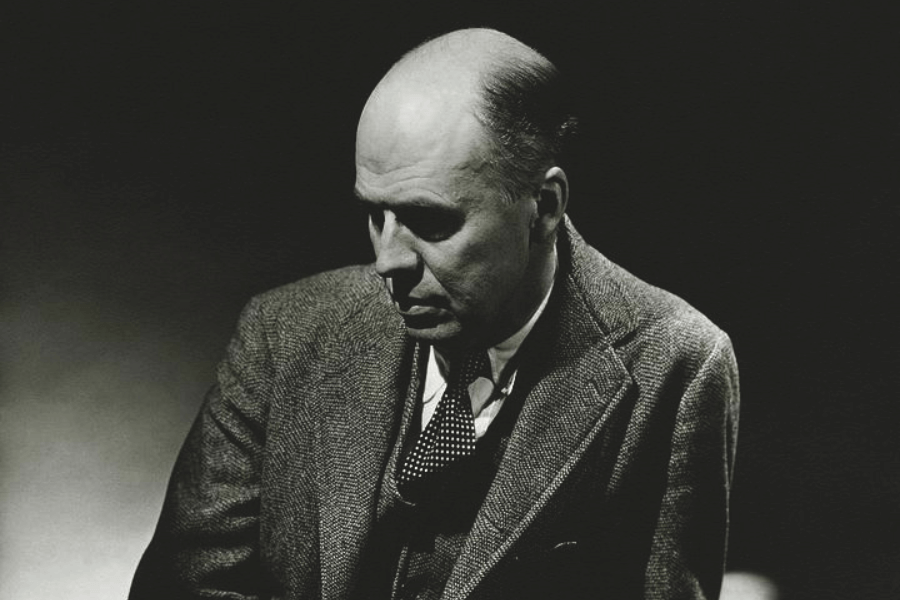

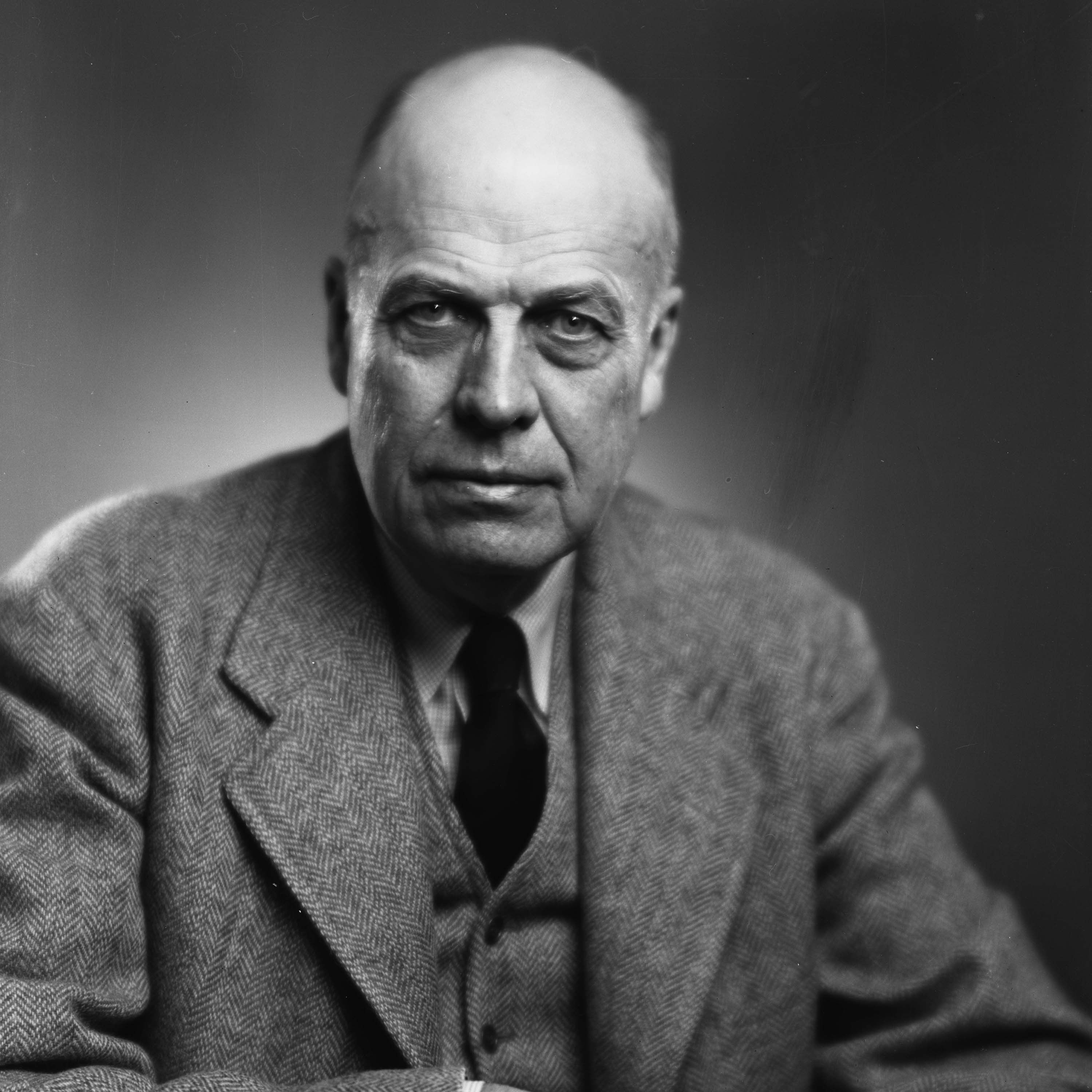

Edward Hopper is a name synonymous with the quiet drama of American life, a painter who captured the hush between moments with an uncanny sensitivity that has kept viewers entranced for generations. From the lonely diners and gas stations to the anonymous hotel rooms and sunlit apartments, Hopper’s world is one where nothing seems to happen, yet everything somehow does. But behind the familiar frames and celebrated canvases lies a story that has remained, until now, largely untold—a mystery surrounding a painting that was never publicly shown, rarely discussed, and quietly avoided by curators for reasons that were never officially stated but widely understood. As this hidden work finally comes to light, the world is invited not only to witness its unveiling but to explore the complex legacy of the man who created it.

To understand why a single painting could be so controversial, it’s essential to look at the man behind the art. Edward Hopper’s life was as introspective as his work. Born in 1882 in the riverside town of Nyack, New York, Hopper grew up in a household that prized intellect, civility, and precision. His father, Garrett, was a dry goods merchant with a love for French culture, while his mother, Elizabeth, encouraged his early artistic curiosity. By age ten, Hopper was already sketching boats and riverbanks, developing a disciplined approach to art that would define his career. His childhood drawings, often of schooners moored in sunlight or cottages along the Hudson, revealed a remarkable awareness of space and silence—a sense that stillness itself could be dramatic.

After high school, Hopper briefly pursued naval architecture, drawn to its structural precision, before enrolling in the New York School of Art in 1900. There, he encountered teachers like William Merritt Chase and Kenneth Hayes Miller, but it was Robert Henri, leader of the Ashcan School, who left the deepest mark. Henri’s philosophy was simple: paint life as it is, not as you wish it to be. “Paint what you feel, not what you think you’re supposed to see,” he told his students. Hopper absorbed this lesson but diverged from his peers, painting not the bustling streets but the spaces between events—the empty rooms, the long pauses, the silences that never made the headlines.

By the time he finished his studies in 1906, Hopper had begun to develop his distinctive sense of mood and composition. Like many young artists, he longed to see Europe, and in the same year, he traveled to Paris. Living simply on the Left Bank, Hopper spent his days sketching along the Seine, fascinated by the play of light on the city’s facades. While he admired Monet and Pissarro, Hopper preferred the controlled order of Degas and Courbet, whose work balanced realism with emotional restraint. Paris taught him the power of light—a cool, northern glow that could define a room as much as any object within it. This revelation would echo through his career, illuminating every diner, gas station, and empty room not with narrative, but with pure illumination.

Returning to New York in 1909, Hopper carried with him dozens of sketches and an unshakable sense of direction, but little recognition. For the next decade, he worked primarily as a commercial illustrator, producing advertisements and magazine covers to survive—a compromise he despised but endured. The discipline required to capture attention quickly influenced his approach to composition, though he called the job “a living death.” During these lean years, Hopper lived a solitary life in Manhattan, painting deserted rooftops, sunlit interiors, and lone figures reading near windows—scenes that reflected both his circumstances and his psychology. He painted slowly, meticulously, never rushing an image until it felt inevitable. By his mid-thirties, Hopper had sold almost nothing, but he continued to paint with the quiet conviction that his perspective mattered. “If I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint,” he once remarked—a belief that sustained him when nothing else did.

Everything changed in the early 1920s, thanks to a woman who would become both his love and his muse: Josephine Verstille Nivison, known as Jo. A painter, teacher, and former actress, Jo was vivacious and outspoken, the opposite of Hopper’s reticence and restraint. If he embodied silence, she was its disruption. They had studied under the same teachers at the New York School of Art and reconnected in Gloucester, Massachusetts, painting side by side in the luminous coastal light. Jo’s work was looser, more emotional, full of color and movement, but she recognized in Hopper’s paintings a kind of emotional truth that few critics saw. When Jo was invited to exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, she recommended Hopper’s work, and his painting The Mansard Roof was included and sold almost immediately—his first real breakthrough.

The following year, in 1924, they married in New York City, beginning one of the most complex and creatively productive partnerships in American art. Their marriage was famously turbulent but fiercely interdependent. Jo was not simply Hopper’s wife; she was his muse, model, critic, secretary, and record keeper, appearing in nearly all his major works as the central female figure. Her features—the short auburn hair, reflective gaze, and slightly tense posture—became the visual anchor of his narratives. But Jo’s deeper role was as the organizer of his career, handling correspondence, managing sales, and meticulously documenting his process. Her notes allow art historians today to trace the creation of nearly every major Hopper painting.

Their life together was a study in opposites—emotional heat and withdrawal, expression and restraint, talk and silence. Jo’s diary entries reveal her frustration, especially as her own career faded in the shadow of Hopper’s growing fame. Yet she remained essential to his vision, pushing him when he retreated into silence and reminding him of who he was when he doubted himself. In their Greenwich Village apartment, they worked side by side for more than four decades, the space becoming both studio and stage, laboratory and battleground. Each summer, they escaped to Cape Cod, where Hopper painted some of his most iconic works—Cape Cod Morning, Rooms by the Sea, Second Story Sunlight—all born from the still geometry of that landscape and Jo’s persistent influence.

As Hopper’s fame grew through the late 1920s and 1930s, Jo remained both collaborator and critic, her sharp, unfiltered voice a constant counterpoint to his visual quiet. The two weathered the Great Depression, World War II, and the changing tides of the art world. Movements like Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art came and went, but Hopper refused to follow trends, steadfast in his style. Critics sometimes dismissed his realism as outdated, but Jo stood by him, sometimes resentfully, always faithfully. By the late 1930s, Hopper had become one of the defining American painters of his generation, with exhibitions at the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art cementing his reputation as the chronicler of modern solitude.

Yet Hopper was not a traditionalist. His realism was psychological, even subversive, exposing isolation, alienation, and the quiet ache of modern existence. His paintings carried a muted form of rebellion, resisting the optimism that dominated postwar art and ignoring the glossy narratives of progress and suburban comfort. His America was emotionally cold, structurally divided, haunted by loneliness. At a time when the art world shifted toward abstraction—think Pollock’s splatters or Rothko’s color fields—Hopper stood apart, refusing to follow fashion or theory. His art was simple in form but radical in feeling, and this tension between the safe image of the realist painter and the discomfort his best works evoke is key to understanding why one painting might have been deemed too much.

Hopper often painted women in private moments—sitting by a window, undressing, or lost in thought. His work Morning Sun (1952), for example, shows a woman perched on a bed in nothing but a slip, bathed in light but utterly alone. Though tasteful by modern standards, such intimacy once skirted the edge of propriety. His wife Jo recorded that Hopper often wanted to explore the human figure in its truth, not its politeness—a phrase that hinted at something deeper than casual observation. In an era defined by moral conservatism, even quiet sensuality could be labeled indecent. A painting that pushed further, suggesting eroticism or emotional intimacy between socially taboo partners, might easily have been deemed unfit for public display.

Hopper was not a propagandist, but he was not apolitical either. His art was born of skepticism toward modern America—its hurried optimism, commercial gleam, and spiritual vacancy. In the 1930s and 1940s, when federal art programs encouraged patriotic depictions of American life, Hopper’s work stood apart for its cold, detached, sometimes uncomfortably honest views. If the lost painting contained social critique—poverty, racial inequality, postwar disillusionment—curators might have viewed it as a political risk. His silence was his weapon, his refusal to flatter America easily mistaken for subversion. A painting making that critique explicit could have been quietly shelved to protect reputation and funding.

Hopper’s greatest gift was his ability to reveal emotional distance within intimacy. His couples don’t argue; their silence is deafening. In Room in New York (1932), a man reads his newspaper while a woman idly touches piano keys—both trapped in a moment of quiet disconnection. If a lost painting amplified that disconnection by showing anger, despair, or psychological breakdown, it might have felt too raw for mid-century audiences accustomed to the composure of realism. Museums preferred Hopper as the poet of solitude, not its victim. To present him as more emotionally explicit—a man confronting the darkness beneath domestic life—would have risked reshaping his entire image. There is also the possibility that the work touched a subject no one wanted to name: interracial relationships, same-sex intimacy, or hints of violence, all could have triggered censorship in the cultural climate of the time. Hopper’s realism was too clear-eyed to disguise such things behind abstraction.

While the details of the hidden painting remain shrouded in mystery, the depths of Hopper’s most acclaimed works deserve attention. Nighthawks (1942) stands as a masterpiece of atmosphere and suggestion. Through the wide glass of a corner diner, three customers are suspended in a moment that feels both familiar and unreachable. The viewer stands outside in the chill of night, drawn to the glow of the fluorescent interior but kept at a distance by the wall of glass. Hopper offers no story, only atmosphere and the suggestion that something has just ended or might begin. Every line and light feels deliberate, every gesture and pool of light hints at a story whose ending will never be known. The diner becomes both refuge and prison, a place where the fluorescent hum replaces conversation, and where silence, illuminated so beautifully, becomes its own kind of language.

When Hopper died in 1967 at the age of eighty-four, he left behind one of the most quietly powerful bodies of work in American art—and one of the most complicated estates. His widow Jo outlived him by less than a year, and in that brief time became both guardian and victim of his legacy. She bequeathed the couple’s entire artistic estate—roughly three thousand works—to the Whitney Museum of American Art. But the transfer was chaotic, with incomplete records and hundreds of works stored in their Washington Square apartment. In the confusion, mistakes were inevitable, and the mishandling of Hopper’s estate went beyond disorder.

In the 1970s, a Baptist minister named Arthayer R. Sanborn became a central and controversial figure in Hopper scholarship, retaining hundreds of items that technically belonged to the Whitney, including personal letters, notebooks, and even paintings. Many materials remained out of public view for decades, later sold or loaned without clear documentation. Only in the early 2000s did art historians begin to grasp the scale of what had happened. Gail Levin, the leading Hopper scholar, accused Sanborn of withholding and profiting from property that rightfully belonged to the Hopper estate, arguing that the loss of those materials distorted the historical record and left unanswered questions about Hopper’s working process—and possibly about specific paintings that vanished from view after his death.

The controversy around Hopper’s estate reveals the uncomfortable truth that artistic legacy is never purely artistic—it’s institutional. Once an artist dies, their work becomes property, their reputation a brand. The curators, archivists, and scholars who handle it wield enormous influence over what future generations will see. For decades, the Whitney’s narrative of Hopper was tidy and linear: the painter of loneliness, of American quietude, of cinematic stillness. If even one painting contradicted that story—showing rage, sensuality, or despair—it would demand a rewrite of everything we thought we knew about him. For nearly half a century, no one asked too loudly what might still lie unshown in the archives. Now, as Hopper’s long career is reexamined through fresh eyes and recovered works, the possibility of a hidden Hopper painting feels not only plausible, but almost inevitable.

Edward Hopper’s life and art are a testament to the power of seeing the world differently, of finding drama in silence and meaning in stillness. His unique insights into life and art continue to captivate, challenge, and inspire, reminding us that sometimes the most profound stories are the ones left untold. As the mystery surrounding his hidden painting finally begins to unravel, fans and scholars alike are left to wonder: what else lies beneath the surface of America’s quietest rebel?

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load