August 17th, 1987. Spandau Prison, West Berlin. A lone guard completes his rounds in a vast, empty fortress. Only one cell is occupied. Inside, an old man lies motionless on the floor, a thin cord around his neck.

He is prisoner number seven, the last remaining inmate of this Cold War relic. For 21 years, he has known no visitors, no letters, no company. The world’s most isolated man dies alone, his passing preventing neo-Nazi pilgrimages. The world listened to the story, but one document from 1966 changed everything. It wasn’t the most dramatic conviction from Nuremberg, nor the one that drew the biggest headlines, but it exposed why prisoner number seven became a permanent fixture in Spandau’s echoing halls.

This is a story that goes beyond one man’s sentence. It reveals how justice became symbolism, how Cold War rivalries hijacked accountability, and how a single prisoner’s isolation became a standoff between superpowers. Every debate over war crimes, every policy on historical memory traces back to what happened when the victors opened files marked “Spandau Administration Agreement 1947.” The mystery isn’t whether Hess deserved prison—the trials settled that. The question is why the system refused to let him go when all others walked free.

Keep following, because by the end, you’ll see why one empty-winged fortress outlasted the Berlin Wall itself. But first, rewind to May 10th, 1941. The night a lone Messerschmitt roared over the Scottish Moors. Before we unpack that pivotal flight, if you’re drawn to these forgotten corners of World War II history—the trials, the prisons, the lingering shadows of accountability—hit subscribe now. And in the comments, tell me: at what point does punishment become something else?

Eagle’s Nest region, southern Bavaria. Late afternoon, May 10th, 1941. Rudolf Hess, deputy Führer of the Third Reich, climbs into a customized Messerschmitt BF-110 fighter. No escorts, no backup plan beyond a scribbled note left for Hitler. He files a vague flight plan—test flight over the North Sea.

Ground crew watches him vanish into the clouds. Hours later, he crash lands in a farmer’s field near Eaglesham, Scotland. Parachute tangled in hedges, he approaches David McLean, a local plowman, with broken English: “I am Rudolf Hess. Take me to the Duke of Hamilton.” Hess believes Hamilton leads a secret British peace faction.

Historians still debate whether his mission was delusional or a calculated ploy. But that moment flips his trajectory from power center to international enigma. Captured immediately, he’s shipped to the Tower of London. Churchill dubs it “the Hess riddle.” Hitler declares him mad and a traitor, publicly disowning him—privately, he is relieved.

Zoom out. This isn’t random. Hess joined the Nazi Party in 1920, ghostwrote Mein Kampf during Landsberg imprisonment, and became a loyal enforcer with occult interests that fueled Hitler’s obsessions. By 1941, Germany is stalled on two fronts. Hess dreams of brokering an armistice—Britain exits the war, focuses on the Soviets.

His solo mission bypasses diplomacy, betting on aristocratic contacts from the 1936 Olympics. It fails spectacularly. The real consequence unfolds postwar, because that Scottish field becomes exhibit one in a larger case. October 18th, 1945, Nuremberg Palace of Justice. Allied prosecutors sift mountains of documents.

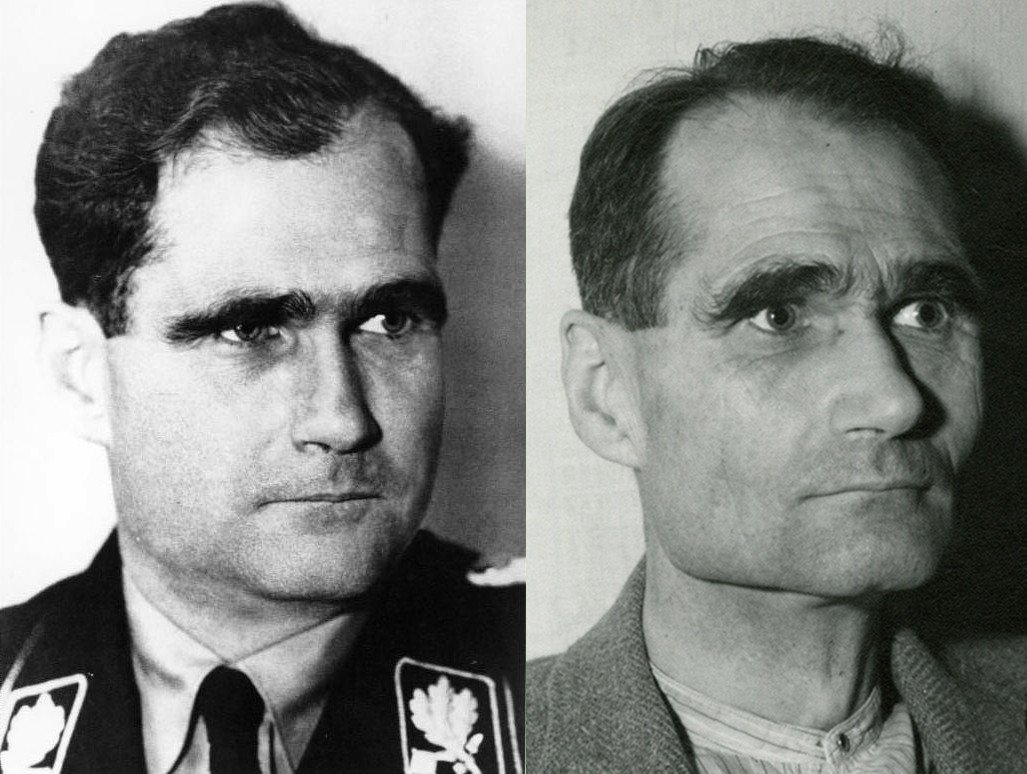

Hess appears before the International Military Tribunal. Gaunt and erratic, his defense claims amnesia from crash injuries. Psychiatrists debate his sanity. The tribunal rules him competent to stand trial. He is charged with conspiracy and crimes against peace—planning aggressive war.

Judges deliberate. Other defendants face death or life. Hess draws life imprisonment, not for battlefield orders, but for ideological foundation. Sentenced October 1st, 1946, he is transferred to Spandau with six others. Göring suicides before execution; others hang.

Survivors Hess, Speer, Neurath, Funk, Raeder, Dönitz, Schirach. Fast forward to Spandau Prison, British sector, West Berlin, October 1947. The prison opens, jointly administered by four powers rotating monthly command. Rules are ironclad: no releases without consensus. Annual reviews are possible, but veto power is absolute.

The prison holds 600 cells for seven men—overkill symbolism. Hess is number seven. The routine grinds: 7 a.m. wake-up, manual labor, monitored walks. Cracks emerge early. In 1954, Admiral Raeder is released for health at age 79.

The oldest inmate, his release is unanimously approved. In 1955, economics minister Funk is freed with terminal cancer. In 1957, diplomat Neurath, age 83, is frail and released. In 1958, Grand Admiral Dönitz, submarine commander, is freed due to health decline. Each exit is unanimous or nearly so—the prison empties by 1960.

Speer and Schirach serve reduced sentences and are paroled in 1966 for good behavior, under international pressure. Enter the deadlock: October 1966, Spandau now houses three—Hess, Speer, Schirach. The Soviet Union blocks further releases as the Cold War intensifies and Berlin divides. Khrushchev demands Hess stay as a Nazi symbol. Western powers push for mercy—age 72, Parkinson’s tremors, incontinence.

Family petitions flood in—wife Ilse, son Wolf Rüdiger. Red Cross appeals. Petitions to the UN, but Moscow vetoes. Speer and Schirach walk free on October 31st, 1966. Trucks carry them out; Hess watches from his cell window.

From this point, he’s alone—one man in a facility for hundreds. Guards rotate: 165 Soviet, 75 British, 40 French, 30 American annually. The cost runs into millions yearly—a taxpayer-funded standoff. Here’s the pivot you need to understand: solitary confinement wasn’t oversight, it was policy. The Soviet rationale: prevent martyr status.

Hess’s son tours Europe, claims father is a saint, peace envoy. Neo-Nazi groups circle. Moscow fears Spandau as a rallying point. Western allies counter: humanity demands release. Annual reviews become rituals—1967, US proposes parole; USSR says no.

1968, France suggests medical discharge—veto pattern locks in. Hess deteriorates: falls, fractures, blind in one eye, wheelchair-bound. Yet the system endures because it serves dual purposes: punishment for Hess, leverage for Soviets. The Soviets wield the veto like a weapon. In broader context, Berlin’s crisis—1948 blockade, 1961 wall—mirrors the prison as a microcosm.

Hess complains, “I am the last hostage.” Family smuggles messages. In 1977, Wolf petitions Carter—denied. Public pressure builds; media tours empty corridors and echoing cells. Hess gardens alone, tends his plot obsessively, reads smuggled books, whispers to birds.

The psychological toll is immense, but the system remains rigid. Zoom in on the 1970s—health crises mount. In 1976, Hess is briefly hospitalized, put on suicide watch. Official reports cite depression and isolation-induced symptoms. Western doctors urge release; Soviets insist he is faking.

On his 85th birthday, protests erupt outside. Gorbachev signals a thaw, but no veto is lifted. Allies debate demolition pre-release to prevent a shrine. Hess endures, walking frail laps, one guard per shift, always in the shadows. Meals are eaten alone, no radio, limited news—the world moves on.

The official verdict stands: self-inflicted death. His body is returned to family and buried. Neo-Nazis attend the funeral, fears realized. Allies act: on August 31st, demolition crews level the prison. Trees are planted; the site becomes a park, then a mall—no marker, by Soviet approval.

The real evidence trail is in declassified cables. In 1966, a Soviet memo states Hess remains a guarantor against revanchism. The US State Department calls his detention an anachronism that burdens the alliance. Four-power logs show 21 years of vetoes. Nuremberg transcripts justify the life-term as an ideological architect.

Hess’s flight file—peace ploy or madness—remains unresolved. This bureaucracy wasn’t vengeance alone, but Cold War utility. Hess became a pawn; justice was delayed into absurdity. The system punished one but symbolized all. If this unraveling of hidden histories grips you, smash that like button for more deep dives, and comment: was keeping him alone justice, or geopolitical theater?

Spandau’s four-power yoke was unique—no other Nuremberg site endured. Symbolism outweighed cost. Hess embodied unresolved Nazi questions. The flight mystery fueled theories: doubles, mind control, real peace bid, rogue actor, or authorized mission. British files sealed until 2017, partially released, reveal no smoking gun.

Daily reality post-1966 was surreal. Hess paced a 300-meter track alone, watched by guards in towers with rifles at the ready. Soviet shifts were strictest—no conversation. British were laxer, allowing chess games. French conducted medical checks; Americans brought holiday treats.

He manipulated the system, faking illnesses for hospital breaks. In 1969, a colon cancer scare proved benign. He leveraged isolation complaints, family remained his lifeline. Ilse visited monthly until a 1969 ban; son Wolf in 1970, with censored letters. Wolf published “My Father Rudolf Hess,” portraying him as a victim and boosting far-right narratives.

The Soviets saw this as a danger. The 1980s thaw tested the system—Reagan, Gorbachev summits, Berlin speech, “Tear down this wall.” Hess died months prior, ironically outliving the division. The Wall fell in 1989. Death fractured the narrative; the official verdict was suicide, but notes were absent.

History recorded prior attempts—1941 parachute faint, 1977 pills. The family’s autopsy found a broken neck, suggesting struggle. MI6 theories, KGB hits—all speculation, unproven. The Berlin coroner found hanging consistent with age and frailty. Demolition was deliberate—bulldozers leveled the site by August 31st.

The legacy is tension: justice versus excess. Nuremberg was a cornerstone of accountability; Spandau became punishment in perpetuity. Hess lived 46 years post-trial, 21 of them alone. Others were freed in a timely manner; the inequality rankled. Moral symbols corrupted the process, but at its core, prisoner seven symbolized unfinished reckoning.

The Cold War kept him breathing. History broadened—postwar justice evolved: Eichmann captured in 1960, Barbie in 1983, Pinochet in 1998. Accountability became transnational, but Spandau remained an outlier—a relic of victor monopoly. The Hess case probes when serving time becomes exhibit. At age 93, rehabilitation was moot; vengeance and deterrence faded.

Modern echoes appear—Guantanamo, solitary icons, politics over persons. The human cost was immense: Hess’s aviator dreams crushed, loyalist betrayed, isolation eroded his mind, paranoia and visions haunted guards. The ghost prison, son’s crusade, petitions, books, and rallies fueled denialism. Allies’ calculus: unity trumped mercy; the fracture risk was too high.

Turning to evidence, the 1966 release proposal met Soviet fears of fascism revival, while the US pushed for compassion. The 1987 cables, post-death, revealed relief; demolition was swift. This wasn’t simple incarceration—it was geopolitical theater with one actor. The moral crux: was punishment proportional? Nuremberg’s intent was finite justice; Spandau became indefinite symbolism.

Justice—eternal or timebound—was fueled by documents that outlasted the men who signed them. Declassified now, those papers reveal the quiet calculus behind the vetoes. Soviet diplomats in 1967 described Hess as the living embodiment of fascist guilt, a bargaining chip in Berlin negotiations. Releasing him risked unraveling the narrative all four powers had built since 1945. That narrative rested on Nuremberg’s foundation.

Prosecutors argued: without Hess’s scaffolding, there would have been no Holocaust machinery. Life sentence fit; no death due to mental state, but no mercy for the architect. Transfer to Spandau cemented it. The prison opened amid rubble, divided Berlin, four power zones fragile. Article four of the agreement allowed releases only by unanimous vote or 3-to-1 majority, designed for seven inmates anticipating paroles.

Hess, number seven, was youngest at 52; others older, frailer. The system anticipated turnover, but got deadlock instead. Early releases tested the gears: 1954, Raeder’s health petition succeeded with USSR concurrence. Elderly admiral, no threat. 1955, Funk—cancer ravaged—even Soviets nodded.

But by 1966, the landscape shifted. Speer and Schirach, mid-60s, petitioned on humanitarian grounds. The Western trio approved; Moscow alone dissented. Cables hinted at neo-Nazi uptick in West Germany. Hess’s son emerged, touring with “My Father Was No War Criminal,” book sales climbed.

Far-right pamphlets invoked Spandau. The Kremlin saw shrine potential and dropped the veto. On October 31st, 1966, gates opened; Speer emerged, suit pressed, waves briefly. Schirach followed, stooped, peers through bars. Third floor cell, trucks rumble away, silence descends—600 cells, one occupied.

Guards tripled patrols initially, then normalized. Books censored, history banned, novels allowed. He memorized gardens, counted bricks. But isolation bred leverage; Hess adapted. In 1968, his first suicide attempt—hanging, faint—led to hospitalization.

Western doctors diagnosed depression and Parkinson’s onset. Petitions surged; Soviets countered malingering. The pattern repeated: 1976, colon scare, laparotomy revealed nothing, back to cell. Each episode spotlighted the farce. Media leaks called him the world’s loneliest man.

Petitions hit 100,000 signatures by 1970. The UN Human Rights Commission debated, but Soviet block stonewalled. Spandau mirrored Berlin’s Cold War scaffolding: 1948 blockade, 1953 uprising, 1961 wall, prison vetoes sank with crisis. 1967 Six-Day War ripples; Soviets hardened. 1970s, temperatures thawed—Nixon visits China, Helsinki Accords—yet Hess stayed.

Why? Symbol outlived utility. Family fought on the front lines: Ilse Hess, widowed in 1995 but fierce in the 1960s–80s, visited monthly until the 1969 Soviet ban. Smuggled notes told the world of injustice. Wolf Rüdiger founded the Free Rudolf Hess Committee in 1977, toured the US, met congressmen, and claimed his father held secrets on Hitler’s death.

Allied plots and conspiracy whispers grew. MI6 files, partially released in the 1990s, mentioned Hess’s peace feelers pre-flight, fueling doubts. Institutional strain mounted; guards rotated—300 Soviets yearly, stern, no talk; British chatty, slipped chess boards; French doctors noted decline; US humane holiday treats. The cost ballooned—5 million DM annually by 1980. Taxpayers grumbled; Berlin Senate proposed solo funding, but was vetoed.

By 1982, a pivot: at age 88, Hess suffered a false hip fracture, became wheelchair-bound. The Soviet shift hesitated as Gorbachev rose, but no annual review changed anything. French proposed medical release; USSR insisted he was fit enough. Evidence showed Hess gardening, frail but upright. Public protests flared—police clashed with neo-Nazis outside the gates; Moscow cited martyrdom prevention.

Daily grind etched its toll: Hess muttered to sparrows, counted footsteps—four 200-lap circuits yearly. He dreamed of Bavaria. Guards reported paranoia—claims of British poisoning food. Official logs noted a 1978 escape plot rumor, dismissed after investigation. His psychological profile showed resilience; the ideological core remained intact.

Escalate to 1987: the endgame. August 16th, routine—evening meal, guard locks at 9:00 p.m. Morning of the 17th, cell check—body on floor, cord from window latch, neck elongated, ligature marks. Autopsy: asphyxia, self-inflicted, age 93, 59 kg, 110 lbs. The death was contested instantly.

A second exam found a hyoid bone break, suggesting possible homicide. Bruises on arms, guards absent for 30 minutes during a shift change. Theories swirled: KGB silencing, British coverup, flight truths. Official suicide verdict aligned with prior attempts—1941 pills, 1977 razor. The family reburied him in Wunsiedel; 800 attended, skinheads chanted, fears manifest.

Allies acted: on August 31st, demolition crews leveled the prison. The site became a park, then a mall—no marker, by Soviet approval. The underlying documents indicted the system: a 1966 Politburo minute called Hess’s detention a deterrent to fascism revival. US memos from 1982 called it a humanitarian embarrassment; French cables in 1985 urged release.

British files admitted taxpayer strain; the Soviet response was uniform: no. Hess, as frail as he became, embodied a red line—cross it, and the entire Nuremberg verdict risked unraveling in Moscow’s narrative. Keeping him chained fascism. The trial’s core evidence sealed his permanence: Nuremberg document PS2827, Hess’s own 1934 memo consolidating party control.

Prosecutors displayed it: absolute loyalty to the leader, elimination of internal threats. Judges noted: without this deputy structure, no total war apparatus. Lifetime landed precisely because death seemed merciful for the survivor who watched the regime devour itself. Spandau’s early years exposed the system’s fragility. The 1947 intake included seven men of varying health; Hess gardened aggressively, Speer intellectualized labor, Schirach brooded.

Rotations began: American months were lenient, garden expansions allowed; Soviet months, strict—no books past 9 p.m. Tensions simmered. In 1951, suicide pact rumors; Hess declined. The first health plea in 1953—eye issues—was denied. Releases accelerated post-Stalin, but the pattern held: elders first, then in 1966, the tipping point.

Spear’s petition cited 20 years served and demonstrated remorse; Schirach, youth indoctrination repudiated. Western allies signed; the USSR delegate stood alone. Hess remained the highest rank alive—release invited glorification. The vote: three to one. Gates clanged; Hess was alone.

Costs jumped—solo utilities, psychological monitoring. Guards reported inmate talking to shadows. Isolation’s anatomy unfolded in medical appendices—Parkinson’s confirmed in 1969, tremors and falls. Western physicians petitioned annually for mercy; Soviets demanded full exams, claiming malingering. In 1971, a faint heart attack led to a hospital stay and x-rays—a propaganda win for the family.

Wolf Rüdiger amplified press conferences, claiming a torture chamber. Geopolitical undercurrents surged: 1972 Basic Treaty, West Germany; Spandau ignored. 1975 Helsinki Final Act, human rights clause—amnesty sites petitions; Wilson, Ford, veto. Brezhnev: historical justice supersedes family. The siege intensified: Ilse Hess’s 1960s visits, whispers through glass, 1969 ban, Soviet guard overhears plotting.

The son’s committee, fundraisers, and the 1978 book “The Lonely Prisoner” claimed his father knew Hitler escape secrets. Conspiracy theories bloomed—Antarctic bases, doubles, official dismissal as delusion. The daily ledger painted a portrait: 1970s, 200-meter walks shrank to shuffles, diet of potatoes and bread, supplements vetoed, books limited to approved literature, politics banned.

He recited poetry aloud; guards noted a 1974 vision—eagles from the Reich flying. Mental erosion was documented, yet ideology persisted—he saluted guards defiantly. In the 1980s, Reagan-era pressures and Gorbachev’s perestroika hinted at flexibility. In 1984, the US pushed for medical parole; the USSR insisted on stable evidence.

Hess tended roses solo; protests swelled, Berlin rallies clashed with police. The Moscow proof of threat was demonstrated. The endgame mechanics: August 16th, 1987—final meal, soup, bread, 9:00 p.m. lock-in, guards noted calm. At 6:00 a.m., discovery: body twisted, cord taut from bedpost latch.

Forensics found a minimal drop, consistent with frail self-strangulation. Hyoid intact, age atrophy, toxicology clean, prior attempts documented—1941 cyanide, 1977 window jump. Controversies were labeled as alleged. The son’s 1988 autopsy push found external strangulation marks; independent review was inconclusive, but hanging was viable. KGB and MI6 hit claims remained unproven speculation.

Hess held no postwar leverage; the official verdict was suicide, aligning with prior attempts. Allies exhaled collectively; demolition was greenlit August 20th, explosives set August 31st, towers crumpled in sequence, rubble pulverized, site seeded with grass, retail built in 1994. The void was absolute. Archival verdict: the 1976 directive, the Politburo’s anti-fascist consensus, CIA’s 1985 moral liability, and Thatcher’s 1984 dispatch all pointed to the same conclusion.

Nuremberg’s anchor was Hess’s 1938 address on eternal vigilance. The mechanism was pristine, not neglect—engineered for eternity. If this forensic disassembly of history’s locked rooms resonates, like and comment: do symbols sustain justice or corrode it? The flight forensics sharpen the anomaly: May 10th, 1941—modified BF 110, navigation log tampered, testimony claims peace channel via astrologer, captors found no prior sanction.

Hitler’s rage, the traitor designation, the Nuremberg theater, amnesia ploy—all crumbled under evidence. 1921 party bylaws, 1934 deputy orders, 1939 war speeches—verdict: crimes against peace. Spandau evolved from collective to spectral; 1950s camaraderie faded, 1960s releases hollowed triumph for survivors. Hess was betrayed by victors; Cold War Inc. Checkpoint Charlie, prison echoes, NATO doubles, veto mirrors.

Campaigns crescendoed—1982 petitions, 1 million signatures, European Parliament motion, veto, death, legacy. The grave was desecrated in the 2010s, exhumed in 2020, cremated, ashes scattered at sea, gravestone destroyed, church erased his name. The first erasure was the prison; the second, the grave. The son’s crusade dimmed with age; Wolf Rüdiger died in 2001. The Hess bloodline severed, the Third Reich’s tether snapped.

Allied archives remain partially sealed—British MI files set for 2041 release, American OSS files declassified but redacted, Soviet KGB files lost in post-USSR chaos. What remains hidden is likely mundane bureaucracy, not sinister pacts—but gaps feed speculation eternally. Modern parallels pierce: Guantanamo detainees held for decades, solitary confinement debates, psychological torture—Spandau as precedent. Cautionary systems ossify; individuals dissolve; justice requires sunset clauses and humanity checks.

Nuremberg’s dual legacy crystallizes: trials as rule of law triumph, accountability framework; Spandau as the same laws’ perversion—punishment perpetuity unjustified. Both are true simultaneously: progress and pathology intertwined. The core moral fracture persists: when does punishment become performance? Hess’s crimes were ideological enablement, legal framework for genocide; his sentence was life, served for 46 years, 21 in solitary.

Was this proportionate? Judges intended finite sentences; vetoes imposed infinite ones. Was it justice or geopolitical theater? The human cost tallied beyond Hess: guards’ psychological burden, elevated PTSD and depression, families’ multigenerational trauma, taxpayers’ millions funding a symbol. Society set a precedent that punishment serves power, not principle.

A final question looms: what did 46 years achieve? Deterrence was negligible—neo-Nazis emerged anyway. Accountability was served after 25 years; rehabilitation was unachieved, ideology unshaken. Symbolism became a Cold War relic, not a moral beacon. The cost exceeded benefit by any measure except one: alliance cohesion.

Hess’s life was traded for diplomatic convenience. The system autopsy reveals justice is vulnerable to capture by interests divorced from its purpose. Nuremberg birthed accountability; Spandau demonstrated its limits. When symbols supersede individuals, law becomes a tool, not a principle. Here’s what prisoner number seven’s 46-year sentence teaches: institutions must sunset, reviews must mandate action, and mercy cannot yield to veto indefinitely.

Otherwise, justice becomes indistinguishable from revenge, punishment from politics, and history from theater. Rudolf Hess died alone because four powers couldn’t agree he’d suffered enough. The prison fell because they finally agreed it symbolized too much. Between those coordinates lies the distance between justice and its shadow. Was the last prisoner a war criminal who deserved every year, or an old man tortured by bureaucracy?

Both, and neither fully. History rarely offers clean verdicts. But it does offer this: when we build cages that outlast their purpose, we imprison ourselves in the contradictions. Drop your verdict below. At what point does accountability become cruelty? When does remembering the past imprison the present? These aren’t theoretical questions—they shape how we handle justice today.

If this excavation of history’s forgotten cells revealed something you didn’t know, subscribe. More hidden chapters of World War II’s aftermath are coming. Until then, remember: the longest sentences aren’t always served by the guilty alone. Sometimes, entire systems serve time for refusing to evolve.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load