In the summer of 1990, two young hikers—Geoff Hood and Molly LaRue—stood atop Maine’s Katahdin summit, grinning beneath heavy packs, the wind teasing their hair as they posed for a photo that would mark the start of their Appalachian Trail adventure. That image, a simple snapshot of joy and anticipation, was destined to become more than just a keepsake for their families. Thirty-five years later, as the Appalachian Trail Conservancy prepared a commemorative safety exhibit, experts revisited the photo with new technology and sharper eyes. What they found when they zoomed in would send chills through anyone who’s ever trusted a stranger on a trail.

The photo was meant to be the exhibit’s warm welcome, a reminder of why the trail draws so many to its winding paths and wild beauty. Geoff and Molly’s families had given permission for its use, but with strict instructions: no sensationalism, no speculation—just facts and lessons to help future hikers. The Conservancy’s goal was simple: honor the memory of two beloved hikers while teaching others how to stay safe.

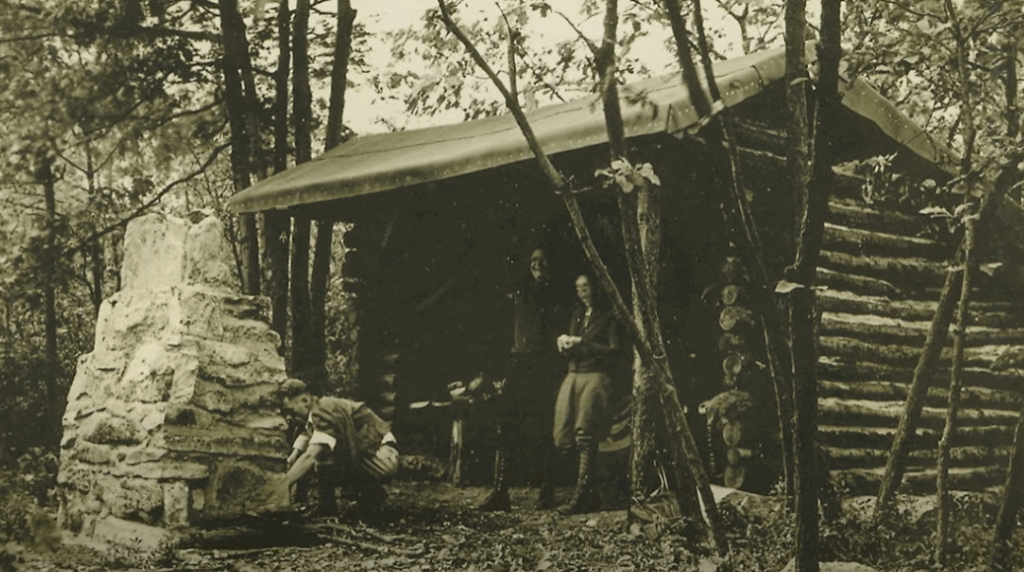

But as an imaging technician enhanced the photo, she noticed something odd. Geoff’s utility cord, looped around his hip belt, wasn’t tied in a casual knot. It was a slip noose variant—a knot she’d seen used for restraint, not gear. As she adjusted the lighting, another detail emerged: the polished lid of Molly’s cookpot, strapped high on her pack, reflected a faint, shadowy figure. The person wore a cap with its brim forward, standing exactly where someone might linger after offering, “Want me to take your picture?” At the base of the frame, three sets of footprints pressed into the sandy grit. Two matched the couple’s boots. The third, deeper and chevron-lugged, belonged to a military-issue combat boot—an unusual choice for a casual hiker, but common enough among those traveling light on a budget.

Karen Lutz, the Conservancy’s Mid-Atlantic director, listened as the team described what they’d found. She cautioned against jumping to conclusions. “We’re not here to invent villains,” she said. “If there’s something in that photo, it has to teach.” Within the hour, she was on the phone with former prosecutor R. Scott Kramer and retired state police investigator Bob Howell. Their directive: examine the image for method, not identity. Compare patterns, not faces. The words “Possible breakthrough” were scrawled across the authorization memo.

For decades, the murders of Geoff Hood and Molly LaRue had haunted the trail community. Paul David Cruz, a drifter, was convicted of killing them at Thelma Marks shelter in Pennsylvania, but questions lingered about when and how he first crossed their path. Could the clues in the Katahdin photo reveal that their killer had been closer than anyone realized, even before that tragic night?

The investigation was tightly controlled. Kramer warned that the photo wasn’t police evidence—just a family copy, lacking a certified chain of custody. Drawing lines between it and the crime scene would be risky. “Inference creep is how lawsuits happen,” he said. The imaging technician pushed back, arguing that they were simply comparing knot types, not assigning blame. But the line between observation and accusation was razor thin.

The board debated its next steps. Were they about to suggest that Geoff and Molly should have recognized a threat that day? Would the hiking community see this as victim-blaming? Karen insisted the value was in teaching how ordinary interactions—a friendly offer to take a photo, a neatly tied knot—could later reveal patterns of danger, not in blaming the victims.

Retired investigator Bob Howell agreed to share crime scene photos of the bindings used at Thelma Marks, with one condition: “No one in your shop says this photo places Cruz at Katahdin. The moment you cross into identity, you lose me.” Karen promised to stick to geometry, not faces.

At a training facility, rope technician Alons Derry examined the knot in the summit photo and the bindings from the shelter. “Slip noose variant,” he said. “Old school. Two turns here, load-bearing hitch, tag end tucked against the standing part. That’s the same dressing pattern. Not your average bear hang knot. It’s optimized for restraint.” The implication was clear: the knot was deliberate, not accidental.

A forensic podiatrist, Dr. Melinda Shore, compared the boot print in the photo to casts from the shelter. “US military jungle boot, late ‘80s issue,” she explained. Common enough, but the left foot imprint showed unique wear—overpronation on the inner heel edge, a gait signature that matched the shelter prints. “Compelling isn’t proof,” Howell cautioned. But the technical match was hard to ignore.

As the evidence mounted, the story grew more complex. Geoff and Molly had been the kind of hikers who embodied the spirit of the Appalachian Trail—resourceful, patient, eager to savor every moment. They moved at a pace that allowed for discovery and connection, trusting the rhythms of the trail and the strangers they met. By early September, those rhythms carried them into Pennsylvania’s ridges, and ultimately to Thelma Marks shelter, where their trust was shattered.

The photo from Katahdin, enhanced and scrutinized, offered up fragments—a knot, a tread, a reflection—that suggested the method used at Thelma Marks might have been present in their lives weeks earlier. The imaging expert pointed out the shape in Molly’s cookpot reflection: cap brim forward, squared shoulders, elbows bent as if lowering something from eye level. “Consistent with someone who has just handed the camera back after the pose. Completely ordinary behavior. The menace isn’t in identity. It’s in proximity.”

The tension in the room was palpable. If the knot and tread showed method, the reflection showed opportunity. An invisible thread tied the summit to the shelter, hinting that the killer may have been a passing figure in Geoff and Molly’s world before that September morning—close enough to offer a hand, a camera, or a knot without suspicion.

Karen insisted the families hear the findings before any public release. On a video call, she laid out the evidence with care: the knot’s technical match, the unique boot print, the proximity implied by the reflection. “This doesn’t shift blame,” she said. “It doesn’t rewrite the case, but it does suggest that some of the method was already present in their world before that morning in Pennsylvania.” After a long silence, Geoff’s and Molly’s families agreed: if these findings could help future hikers spot danger, even when it feels harmless, then the story should be told.

Further research revealed similar knots tied at shelters in Vermont and Maine, logbook entries describing a quiet man in combat boots offering to show “a better way to tie off your gear.” Not every clue reinforced the theory—some boot prints appeared in places Cruz couldn’t have been—but a pattern emerged. Knots, boot prints, and accounts of strangers inserting themselves into mundane trail tasks. The evidence didn’t prove that Geoff and Molly met their killer before Thelma Marks, but it challenged the comfort of believing their encounter was pure chance.

As the roundtable debated how much to reveal, the evidence boards grew crowded with summit photo segments, knot diagrams, boot print tracings, and logbook excerpts. Each clue was ordinary enough to dismiss in isolation. Together, they outlined a consistent approach—a method that could move beside you on the trail for miles, unnoticed until it was too late.

When Howell shared an internal report noting a man in combat boots had been logged by shelter visitors two days before Geoff and Molly reached Thelma Marks, the room went silent. “That puts him,” Karen said quietly, “within striking distance—not in theory, in proximity.” Kramer added, “By multiple accounts, interacting—not a phantom, an acquaintance of the trail.”

Suddenly, the summit photo was more than a memento. Thirty-five years later, its quiet details—the knot, the tread, the reflection—hinted at a shocking truth: the person who would take their lives had likely already stepped into their frame, not as a stranger in the night, but as a casual presence in daylight. What was once seen as a single tragic encounter now suggested a longer shadow, a method patiently moving along the trail.

For the team, the lesson was clear. Danger doesn’t always come from the dark edges; sometimes it walks right beside you. With the families’ blessing, the Conservancy prepared to share these findings with the hiking community—not to sensationalize, but to teach. The hope is that future hikers will notice the patterns, protect each other, and keep the trail as safe as it was meant to be.

What do you think about revealing history through images like this? Let’s talk in the comments. And until next time, walk safe, walk aware, and keep your eyes open.

News

My Brother Betrayed Me by Getting My Fiancée Pregnant, My Parents Tried to Force Me to Forgive Them, and When I Finally Fought Back, the Entire Family Turned Against Me—So I Cut Them All Off, Filed Restraining Orders, Survived Their Lies, and Escaped to Build a New Life Alone.

The moment my life fell apart didn’t come with thunder, lightning, or any dramatic music. It arrived quietly, with my…

You’re not even half the woman my mother is!” my daughter-in-law said at dinner. I pushed my chair back and replied, “Then she can start paying your rent.” My son froze in shock: “Rent? What rent?!

“You’re not even half the woman my mother is!” my daughter-in-law, Kendra, spat across the dinner table. Her voice sliced…

My mom handed me their new will. ‘Everything will go to “Mark” and his kids. You won’t get a single cent!’ I smiled, ‘Then don’t expect a single cent from me!’ I left and did what I should have done a long time ago. Then… their lives turned.

I never expected my life to split in half in a single afternoon, but it did the moment my mother…

At my son’s wedding, he shouted, ‘Get out, mom! My fiancée doesn’t want you here.’ I walked away in silence, holding back the storm. The next morning, he called, ‘Mom, I need the ranch keys.’ I took a deep breath… and told him four words he’ll never forget.

The church was filled with soft music, white roses, and quiet whispers. I sat in the third row, hands folded…

Human connection revealed through 300 letters between a 15-year-old killer and the victim’s nephew.

April asked her younger sister, Denise, to come along and slipped an extra kitchen knife into her jacket pocket. Paula…

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

End of content

No more pages to load