On a sweltering July morning in 1841, the fields of Hollow Creek Plantation in Ascension County, Louisiana, stood eerily silent. The usual rhythm of labor and command was gone; no voices rose in song, no figures bent over cotton, and not even the dogs barked. By sunrise, it was clear that something unprecedented had happened: 87 enslaved men, women, and children had vanished overnight without a trace. The only remains of the previous night’s events were three overseers lying dead—faces frozen in terror, lips gray from poison—and a cryptic note left on the desk of the infamous Colonel August Whitley. Scrawled in charcoal on torn paper, it read: “We did not run. We returned.” To this day, the note resides in the Louisiana State Library archives, a relic of a mystery that has never been solved.

Hollow Creek Plantation was a place where silence reigned, and fear was the law. Colonel Whitley, a man whose reputation for cruelty preceded him, forbade singing, praying, and gathering after dark. His discipline was marked—literally—by branding those who broke his rules with a searing “W” on their shoulders. By the summer of 1841, nearly half the enslaved population bore his mark, and the local sheriff had visited only once, leaving quickly and warning, “Only that place ain’t right. Something wrong in the air there.” Yet, as long as the cotton grew and the money flowed, nobody asked questions—until the morning everything changed.

When supply man Thomas Bodri arrived with his nephew Pierre, he found Hollow Creek transformed. The main house’s door stood open, and the overseers lay dead—one on the veranda, one inside the doorway, one slumped on the back porch. The signs of oleander poisoning were unmistakable, and the food on the table was untouched, crawling with ants. But the true shock came when Thomas checked the slave cabins. Every door was open. Every bed was made. Every cooking pot was cold. Blankets lay folded, and a child’s corn husk doll sat abandoned in the dirt. Not a single person remained.

Sheriff Marcus Tibo arrived with deputies, but the search yielded nothing—no tracks, no bodies, no boats on the bayou, and no signs of violence except for the three dead overseers. Colonel Whitley himself was gone, with no trace of his body anywhere on the 300-acre property. The only clue was the message on his desk, “We did not run. We returned.” The investigation expanded to neighboring parishes and auction blocks in New Orleans, but nobody had seen or heard anything. The 87 enslaved people had seemingly vanished into thin air.

Newspapers across the region seized on the story, speculating about foul play and mass escape. A $1,000 reward was posted for information, but no one came forward. Other planters grew nervous, ramping up security and punishing their own enslaved workers more harshly, terrified that the system they depended on was vulnerable. Yet after Hollow Creek’s mass disappearance, there were no further incidents—just the slow return of the plantation to wilderness.

Three weeks later, Sheriff Tibo held a public meeting. He displayed the enigmatic note and fielded questions about the Underground Railroad and local folklore. “That network operates in the north,” he explained. “And even if it did reach here, moving 87 people in one night without anyone noticing is impossible.” The crowd pressed on, asking about voodoo. Tibo dismissed superstition but admitted, “Something happened at Hollow Creek that I cannot explain with reason or evidence.”

Despite the official investigation ending in frustration, the story refused to die. Local people avoided the ruins, and even vagrants stopped looting after reporting being chased away by unseen forces. The property changed hands several times, but no one wanted it, and it eventually reverted to the state. Sheriff Tibo, haunted by the mystery, began a private investigation. He discovered Hollow Creek’s land had a history stretching back to a Spanish mission called San Miguel de los Perdidos—St. Michael of the Lost Ones—built in 1767 as a sanctuary for escaped slaves and local Chitimacha people. The mission was burned in 1779, its inhabitants vanished, and colonial authorities declared the land “cursed.”

Tibo dug through records and found chilling patterns: previous owners had also lost their enslaved workforces under mysterious circumstances. Letters spoke of gatherings at night, of people “waiting for something,” and of overseers refusing to discipline workers. The deeper Tibo looked, the more he saw a history of disappearance and resistance—something older than the plantation itself.

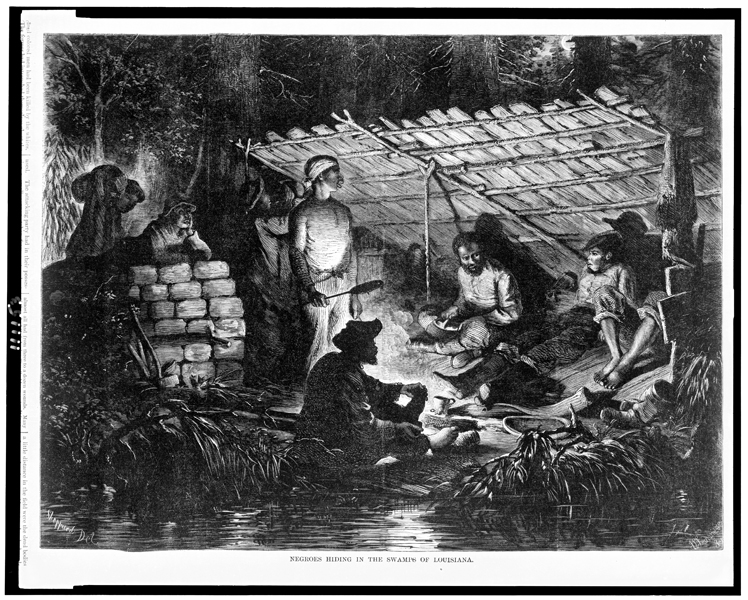

Then came the sightings. In October 1841, a fisherman heard singing from the direction of Hollow Creek—many voices in a language he couldn’t recognize. He found a circle of 87 white stones in the ruins, arranged around a larger central stone. When deputies scattered the stones into the bayou, the circle reappeared within weeks. Reports of singing, shadowy figures, and rebuilt cabins became regular, always at dawn or dusk, always accompanied by a sense of being watched.

The most dramatic incident occurred when a slave patrol tracked runaways to Hollow Creek. They found the fugitives standing in the stone circle, unafraid, as singing erupted from the ruins. The dogs fled, the horses panicked, and the runaways simply disappeared. Later, a rebuilt slave cabin was discovered with an altar: 87 white stones around a red stone, carved with a Congo cosmogram—a symbol of life, death, and rebirth from Central African tradition.

Word spread among enslaved communities. Hollow Creek became a destination, a place whispered about in songs and stories. Runaways headed there, and while some were caught, others simply vanished. A few reappeared far from Louisiana, in free states or Canada, claiming “the ancestors showed us the way.” Tibo documented 12 such cases—people tracked to Hollow Creek who later surfaced hundreds of miles away, with no explanation for their journey.

Planters panicked, and in 1844, a mob burned Hollow Creek to the ground. But even after the land was scorched, witnesses reported hearing singing from the ruins. Tibo, now deeply changed by what he’d seen and heard, visited one last time. In the center of the burned property, he found the stones arranged in a circle, untouched by fire. He heard a voice—calm, unearthly—declare, “We are the ground beneath your feet. You built your world on our bones. You thought you could erase us. But we are still here.” Tibo resigned soon after, unable to reconcile what he’d witnessed with his rational mind.

The legend of Hollow Creek grew. Similar disappearances occurred in Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina, each marked by a note—“We remember the way home,” “The door is open,” “We are calling the others.” The stories spread through the Underground Railroad, with conductors describing fugitives who arrived impossibly fast, carrying white stones and speaking of “spirit roads” and ancestral guidance.

A Quaker woman in Philadelphia recorded an encounter with seven fugitives from Louisiana who claimed they “walked the spirit road.” She wrote, “You think we are slaves because you put chains on us, but you cannot chain the spirit. You cannot enslave the soul. And when enough souls cry out together, something answers.”

Back in Louisiana, Hollow Creek became a pilgrimage site. Enslaved people risked everything to visit, leaving offerings and singing to the 87 who had “returned.” On certain nights, they heard voices singing back, harmonies rising from the ground itself. The story became a source of hope—a symbol that freedom was possible, that the spirit could never be broken.

In 1923, black ministers bought the land where Hollow Creek once stood. They found the stone circle intact, exactly as it had been for more than 80 years. A chapel was built, leaving the stones untouched at its center. Every July 17th, people gather to sing, pray, and remember. Some claim to hear the voices still, singing in languages nobody speaks but everyone understands.

The note from Hollow Creek, “We did not run. We returned,” remains in the Louisiana State Library archives, the most requested item in the collection. Visitors stand before its glass case and weep, sensing the truth that historians often miss. The 87 did not simply escape; they reclaimed sacred ground, anchored their spirits, and opened a door for others. Their story is not a ghost tale—it is a testament to the unbreakable power of memory, faith, and resistance.

Though some dismiss these accounts as folklore, within black communities and churches, the story of Hollow Creek is read as confirmation of what generations have always known: that no system of oppression can ever fully succeed, because the human spirit endures. The 87 became more than victims; they became guardians and guides, a living bridge between worlds.

Today, the chapel still stands, its stone circle weathered but intact. On moonless nights, visitors report hearing the singing—a reminder that freedom is a spiritual condition, and once claimed, it can never be taken away. The legacy of Hollow Creek endures as a permanent challenge to the idea that people can be owned, and as a promise to all who suffer: “We did not run. We returned. We endure. We remember. And we will always answer those who cry out for freedom.”

In telling the story of Hollow Creek, care must be taken to honor the real suffering and resilience of those who lived through slavery, and to avoid sensationalizing the supernatural elements. The narrative’s power lies not in fantasy, but in its reflection of historical truths: the longing for freedom, the strength of community, and the enduring hope that no system can erase. By grounding the account in documented events and lived experiences, and by framing the supernatural as a metaphor for spiritual resistance, the story can captivate readers without crossing into the realm of falsehood or exploitation. The voices of Hollow Creek remind us that history is not only what is written in books, but what is sung in the hearts of those who refuse to be forgotten.

News

It Was Just a Portrait of a Young Couple in 1895 — But Look Closely at Her Hand-HG

The afternoon light fell in gold slants across the long table, catching on stacks of photographs the color of tobacco…

The Plantation Owner Bought the Last Female Slave at Auction… But Her Past Wasn’t What He Expected-HG

The auction house on Broughton Street was never quiet, not even when it pretended to be. The floorboards remembered bare…

The Black girl with a photographic memory — she had a difficult life

In the spring of 1865, as the guns fell silent and the battered South staggered into a new era, a…

A Member of the Tapas 7 Finally Breaks Their Silence — And Their Stunning Revelation Could Change Everything We Thought We Knew About the Madeleine McCann Case

Seventeen years after the world first heard the name Madeleine McCann, a new revelation has shaken the foundations of one…

EXCLUSIVE: Anna Kepner’s ex-boyfriend, Josh Tew, revealed she confided in him about a heated argument with her father that afternoon. Investigators now say timestamps on three text messages he saved could shed new light on her final evening

In a revelation that pierces the veil of the ongoing FBI homicide probe into the death of Florida teen Anna…

NEW LEAK: Anna’s grandmother has revealed that Anna once texted: “I don’t want to be near him, I feel like he follows me everywhere.”

It was supposed to be the trip of a lifetime—a weeklong cruise through turquoise Caribbean waters, a chance for Anna…

End of content

No more pages to load