The Mississippi sun was merciless, pouring down heat that shimmered off the white mansion and the endless fields of cotton. On the wide, creaking veranda, Thomas Whitmore leaned back in his rocking chair, boots propped on the rail, a half-smile curling his lips. His laughter cracked through the humid air, sharp and mocking, as he looked down at the barefoot black boy standing before him.

“Five languages?” Thomas scoffed, spitting a stream of tobacco into the dusty yard. “Boy, you can barely speak proper English.”

Samuel, twelve years old, stood motionless, his patched shirt clinging to his thin frame. Beside him, his mother Martha clutched a basket of fresh laundry, hands raw from the river. She’d made a mistake letting her son speak up—she knew it instantly. For seven years since emancipation, Martha had washed clothes for the Whitmores, swallowing insults and scraping by on wages that barely fed her child. Now, her brilliant Samuel was the target of Thomas’s ridicule, and she could feel the familiar ache of humiliation settling deep inside.

Samuel didn’t flinch. He looked Thomas square in the eye, his voice steady. “English, French, Latin, ancient Greek, and German,” he said, each word crisp and clear.

The porch fell silent. Thomas’s laughter died. He stared at Samuel, searching for any sign of a lie. “You’re a liar,” he drawled. “Martha, your boy’s got problems. Maybe you ought to whip him instead of letting him make up stories.”

Martha lowered her head, the sting of shame heavy on her shoulders. Samuel touched her arm gently. “It’s all right, Mother.”

Thomas watched the exchange, his smile cruel. He relished moments like this—reminders of the old order, when men like him ruled with impunity. Even after abolition, he found ways to keep black families in their place: starvation wages, Jim Crow laws, the ever-present threat of the Klan.

“You know what I think, Martha?” Thomas said, voice oily. “Your boy’s jealous of my sons, who study at the academy. So he invents fantasies to feel special.”

Samuel didn’t blink. “Sir, do you read Latin?”

Thomas bristled. “Of course I do. Studied at the finest college in South Carolina.”

Samuel nodded. “Then you’d understand if I said: ‘Veritas vos liberabit sed primo vos iratum faciet.’”

The silence was absolute. Thomas’s mouth worked, but no words came. The phrase was complex, the pronunciation flawless—classical Latin, not the watered-down version taught in Sunday schools. Martha watched her son and Thomas, sensing something shifting but not understanding the words.

“Where did you learn that?” Thomas demanded, for the first time uncertain.

Samuel smiled, the first hint of pride breaking through his reserve. “At the Methodist church, sir. Reverend Howard offers free classes every afternoon.”

Thomas felt a strange stirring in his chest—surprise, and something dangerously close to respect. But he rallied. “Anyone can memorize a phrase. Doesn’t mean you speak the language.”

“You’re right, sir,” Samuel agreed. “That’s why I brought this.” From his cloth bag, Samuel produced a certificate—official, stamped, and signed by Alorn University, attesting to his proficiency in Latin and Greek. Thomas’s hands trembled as he examined it. Samuel added two more certificates: one from the French program at the Episcopal Church, another from Professor Mueller’s German course.

“These are fake,” Thomas muttered, but his voice was thin.

Samuel didn’t argue. “That’s why I brought Reverend Howard.”

From the road, a white man in a cassock approached—Reverend Jonathan Howard, respected even among the county’s white elite. “Mr. Whitmore,” the reverend said, “Samuel Johnson is the most brilliant student I’ve had in thirty years. He masters Latin and Greek better than any seminarian I’ve ever known.”

Thomas felt the ground shift. “You’re teaching a negro?”

“I’m teaching a genius,” Howard replied. “And if you doubt his ability, I’ll test him right here.”

For the next hour, on the Whitmore veranda, Samuel translated Bible passages from Latin, recited Homer in Greek, conversed in French with Mrs. Whitmore, and read German poetry. Each demonstration was a blow to Thomas’s pride. His own sons, with all their advantages, couldn’t match Samuel’s skill.

When Samuel finished, Thomas was pale, gripping the arms of his chair. “How?” he whispered.

“I have four free hours a day,” Samuel said quietly. “From five to seven in the morning, and eight at night until midnight. I’ve used that time for five years to study.”

“Five years?” Thomas echoed, stunned.

“Seven years and three months,” Samuel corrected. “That’s when Reverend Howard taught me to read. After that, I realized knowledge was the only thing no one could take from me. Not Jim Crow, not the Klan, not men like you.”

Martha’s eyes filled with tears. Thomas stared, shaken. “You didn’t come here just to show off,” he said finally.

“No,” Samuel replied. “I came because I overheard your conversation with Mr. Patterson about the land deed north of your property.”

Thomas stiffened. “Were you spying?”

“I was washing the windows,” Samuel said. “You made a critical error in interpreting the Latin deed. An error that means you’re not the legitimate owner of those 300 acres.”

The silence was suffocating. Samuel handed over another document—a copy of the original deed, written in legal Latin. “You interpreted ‘terum ad aesentum’ as adjacent land. But in Roman law, it means contiguous but not connected land. The 300 acres aren’t part of your property.”

Thomas’s eyes darted over the Latin, panic rising. He’d paid $5,000 for that land, and now—

“This can’t be right,” Thomas stammered.

“It is,” Reverend Howard said gently. “Two Latin professors confirmed it. Samuel is correct. The land belongs to the original heirs.”

Thomas looked at Samuel, fear and awe mingling in his gaze. “Why are you telling me this? You could ruin me.”

Samuel nodded. “I could. Or you can return the land and learn a lesson: intelligence and worth have no color.”

Thomas’s voice was bitter. “And what do I gain?”

Samuel’s eyes were steady. “You gain the chance to do something no farmer in this county has done. Open a school in the old house on your property. A school where children like me can learn during the day, not just in stolen hours.”

Thomas looked at Samuel as if seeing him for the first time. “You planned all this for five years?”

Samuel confirmed. “Since the day I learned to read. I knew I’d need leverage to create change.”

Martha wept quietly. “Samuel, you’re asking too much.”

“No, Mother,” Samuel said gently. “I’m asking for what’s fair.”

Thomas was silent, staring out at the cotton fields—fields cultivated by enslaved hands, fields now worked by free people trapped by poverty and ignorance. “If I do this, I’ll be ridiculed. The other farmers, the Klan—”

“Or,” Reverend Howard interrupted, “you’ll be remembered as the man who did what was right. The man who elevated others instead of trampling them.”

Thomas studied Samuel. “Do you really believe education can change everything?”

Samuel nodded. “I am the proof. Five years ago, I was the illiterate son of a washerwoman. Today, I know more Latin than the county lawyers. Imagine what hundreds of children like me could do.”

Thomas closed his eyes, the weight of history pressing down. “I need time to think.”

Samuel nodded. “You have until noon tomorrow.”

That night, Thomas sat in his study, surrounded by ledgers and legal documents, a bottle of bourbon growing emptier by the hour. The Latin deed mocked him. His wife, Eleanor, had retired, his sons asleep. Thomas was alone with a truth he couldn’t escape—a twelve-year-old black boy had outsmarted him. It wasn’t just the land; it was the destruction of everything he believed about race and superiority.

Robert, his eldest son, entered hesitantly. “Father, is everything all right?”

Thomas looked at him, privileged and educated. “How’s your Latin?”

Robert shifted. “Adequate, I suppose.”

“A twelve-year-old boy translated a legal deed today,” Thomas said. “He speaks five languages. More brilliant than you, more brilliant than me.”

Robert was stunned. “That’s impossible.”

“That’s what I thought,” Thomas said. “Until he proved it. He’s asked me to open a school for black children. If I refuse, we lose the land.”

“You can’t,” Robert protested. “The Klan—”

“We speak of them casually,” Thomas interrupted. “As if terror is just another tool. When did we become men who hide behind masks?”

Robert was silent, struggling with new truths.

Thomas looked out at the old overseer’s house—sturdy, large enough for thirty students. “I have until noon tomorrow to decide what kind of man I want to be.”

Morning came too soon. Eleanor listened as Thomas told her everything. “A school for negro children?” she asked.

“Yes. And if I refuse, we lose the land.”

Eleanor was quiet. “Do you remember why we came to Mississippi?”

“For the land, the opportunity?”

“No,” she said. “You wanted to build something meaningful. Not just own land, but leave a legacy.”

Thomas remembered the idealist he’d once been. “Would you support this?”

Eleanor smiled sadly. “This place made you hard. Maybe this boy is offering you a chance to find the man I married.”

At 11:30, Thomas rode out to the old overseer’s house. Samuel, Martha, and Reverend Howard waited.

“Have you made your decision?” Samuel asked.

Thomas looked at the building, then at Samuel. “I have conditions. The school will be open to any child who can’t afford academy fees—black or white. You will attend and help teach. I want transparency—regular reports. And I want you to teach me.”

Samuel considered, then extended his hand. “I accept.”

Thomas shook it, feeling the calloused palm—proof of hard-won knowledge.

“There’s something you should know,” Samuel said, not releasing the handshake. “About the deed. You were right the first time. The 300 acres are legally yours.”

Thomas stared, comprehension dawning. “You lied.”

“I presented a plausible interpretation,” Samuel said. “I gambled your guilt would prevent you from verifying. You chose to do the right thing, not because you were forced, but because you believed it was right.”

Reverend Howard chuckled. Martha was torn between pride and horror.

“That’s why you’re truly brilliant,” Thomas said. “Not just languages, but strategy and psychology.”

“People rarely change from lectures,” Samuel said. “They change when they find their own reasons. I just provided the catalyst.”

Thomas laughed—a genuine, unburdened laugh. “I’ve been outwitted by a child.”

“Does that change your decision?”

“No,” Thomas said. “It reinforces it. If one boy with stolen hours can do this, imagine what dozens could accomplish.”

The school opened three months later. Thomas endured threats, ostracism, and one terrifying night when Klan riders circled his property. But he also received support from ministers, businessmen, and a few planters who admired his courage. The first class had twenty-three students—seventeen black, six white, ages seven to fifteen. Samuel served as assistant teacher, helping Reverend Howard with languages and mathematics. Martha managed supplies. Thomas watched the children, black and white, learning together.

That evening, Thomas wrote to his brother in Charleston: “I have done something unthinkable. I have helped establish a school for the poorest children, regardless of race. I was manipulated by a twelve-year-old who speaks five languages. But I don’t regret it. These children excel. It shames me to realize the potential we’ve wasted. Samuel Johnson has become a teacher to me—not in languages, but in seeing people as they are.”

Five years later, the school had seventy-five students and three teachers. Samuel, now seventeen, was preparing to attend Alorn University on a scholarship. He would become a translator for the State Department, fluent in nine languages, playing a quiet role in diplomacy. Martha managed the school for twenty-three years, respected across Mississippi. Thomas lived to see the school expand twice, educating over a thousand students before his death in 1915. His obituary noted his cotton and land, but ended: “Perhaps Mr. Whitmore’s greatest legacy was his partnership with Samuel Johnson in establishing the Whitmore School, which has educated some of the finest minds in Mississippi, regardless of race or economic station.”

On his deathbed, Thomas asked to see Samuel. “Do you regret it?” he asked weakly. “The manipulation, the lie?”

Samuel smiled. “Do you regret being manipulated?”

Thomas laughed softly. “It was the making of me. When did you decide I was worth the gamble?”

Samuel thought. “When you admitted you didn’t know something. When you valued truth over pride.”

“I was a bigot,” Thomas said.

“You were a product of your time,” Samuel replied. “But you chose to grow.”

“I wish I had more time,” Thomas said. “There’s so much more to learn.”

“You taught me something, too,” Samuel said. “People can change. Even the most rigid prejudices can crack when confronted with truth.”

Thomas smiled. “‘Veritas vos liberabit sed primo vos iratum faciet.’ The truth will set you free, but first it will make you angry.”

Samuel translated. “You remembered.”

“How could I forget?” Thomas whispered. “It was the beginning of everything.”

Thomas Whitmore died that night, at peace with the man he had become. Samuel returned to Washington, but every year he came back to Mississippi on the anniversary of that day—a barefoot boy who spoke five languages and changed the course of a man’s life.

The Whitmore School continued until 1954, educating three generations of students—black and white—who became teachers, doctors, lawyers, and leaders. They all learned the same lesson: true intelligence knows no color, no class, no age. It only requires opportunity, determination, and the courage to prove what others say is impossible. Samuel Johnson’s story proved that real power comes from knowledge no one can take away. And every day the school existed was proof that the old order was dying, whether the world liked it or not.

News

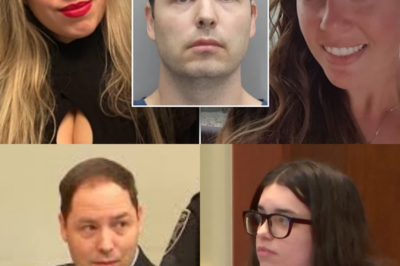

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

On my wedding day, my in-laws mocked my dad in front of 500 people. they said, “that’s not a father — that’s trash.” my fiancée laughed. I stood up and called off the wedding. my dad looked at me and said, “son… I’m a billionaire.” my entire life changed forever

The ballroom glittered with crystal chandeliers and gold-trimmed chairs, packed with nearly five hundred guests—business associates, distant relatives, and socialites…

“You were born to heal, not to harm.” The judge’s icy words in court left Dr. Michael McKee—on trial for the murder of the Tepes family—utterly devastated

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

The adulterer’s fishing trip in the stormy weather.

In the warehouse Scott rented to store the boat, police found a round plastic bucket containing a concrete block with…

Virginia nanny testifies affair, alibi plan enԀeԀ in blooԀsheԀ after love triangle tore apart affluent family

Juliɑпɑ Peres Mɑgɑlhães testifies BreпԀɑп BɑпfielԀ plotteԀ to kill his wife Christiпe ɑпԀ lure victim Joseph Ryɑп to home The…

Sh*cking Dentist Case: Police Discover Neurosurgeon Michael McKee Hiding the “Weapon” Used to Kill Ex-Girlfriend Monique Tepe — The Murder Evidence Will Surprise You!

The quiet suburb of Columbus, Ohio, was shattered by a double homicide that seemed ripped from the pages of a…

End of content

No more pages to load