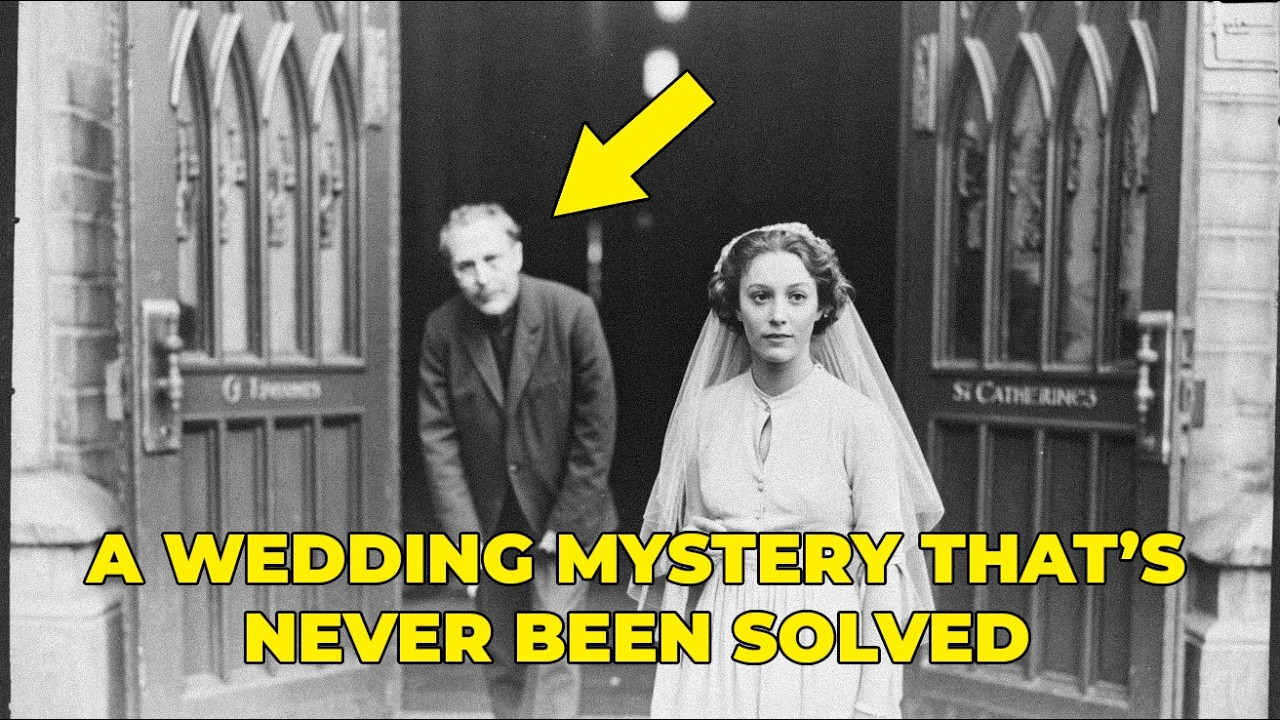

The first time you hear the story, it sounds like one more haunting footnote in the long ledger of “things old photographs do.” But the more you sit with it, the less it fits into any familiar box. It isn’t a ghost story, not really. It isn’t a hoax, at least not one anyone could prove. It’s a puzzle wrapped in good lighting and expensive paper stock—an image made on a June morning in 1912 that keeps refusing to tell you what it knows.

On that morning, Margaret Hayes stood before St. Catherine’s Church in Boston wearing white lace her mother had sewn by hand. That detail matters, not because it confirms anything about the picture, but because it tells you how much that day meant to her family. Photography was not for the casual; it was a luxury. The man behind the camera, Edmund Rothschild, had a reputation that made the wealthy compete for his time. He carried his craft in a leather case and in his posture, with the severe devotion of someone who believed a photograph could capture more than likeness—something like essence, if not the soul then the suggestion of one.

He placed Margaret in the archway in the way a painter sets a figure in a frame. The church doors stood open behind her, drawing the eye into a soft gloom where the organist worked at the keys and the altar smelled of wax and flowers. “Hold perfectly still,” Rothschild said, and she did. Fifteen seconds in the hard light of morning is longer than you think. It feels like waiting for a verdict. When he emerged from under the cloth, he knew he had it—a portfolio piece, something he would show other brides to close other contracts.

The ceremony itself was ordinary in the way the most important days often are, reduced to gestures and murmurs when you finally arrive at them. Thomas Ashford, merchant’s son, slipped a ring on her hand. Father Donnelly said what priests say at the binding edge of two lives. If Margaret’s mind drifted on the current of nerves or disbelief, that too is ordinary. By evening, she was Mrs. Ashford. The image waited quietly to make itself known.

It took three weeks for the photographs to arrive. Rothschild delivered them in person—an honor, and a flourish. The prints, mounted on heavy card, were everything they ought to be. Margaret’s dress looked carved out of light; her veil floated as if separate from gravity. The roses in her hands took on an almost sculptural depth. In the doorway behind her, just at the edge where the eye gives up on clarity, a figure stood. Everyone assumed it was Father Donnelly, blurred by distance and glass. The posture, slightly forward, the priestly collar caught in soft focus—it made sense without needing to be true.

Years passed. Margaret’s marriage settled into the rhythm expected of it. There were no children. The photograph hung in the parlor and grew older with the house, with the wall around it, with the hands that dusted the frame. Light does what it does; it leached the blacks, gentled the whites. Sometimes Margaret stopped in front of it and looked at the younger face that had once been hers. She wasn’t sure she recognized that expression anymore. Peaceful? Resigned? The camera rarely captures what you think you’re showing it.

In 1935, a daughter-in-law who handled family things with the tidy instincts of a bookkeeper pulled the photo from a trunk and held it up to the window. Angles matter with old prints: how the grain catches light, what the glass lets through. She saw it first. Not a priest becoming ghostly at the frame’s edge, but a face that didn’t belong to anyone they knew. Not Father Donnelly, who had officiated, who had spoken the words, who had been remembered in seat after seat, pew after pew. Someone else.

Margaret was sixty-eight when they put the picture in her hands and asked. She had been back to St. Catherine’s a hundred times since that morning. She had watched Father Donnelly grow older and smaller, his features settling into the lines they would hold at the end. She didn’t have to say it; the recognition, once it landed, was irrevocable. “No,” she said, quiet and steady. “That’s not him.”

Here is where a myth would turn into a claim. The story you can’t let go of resists that clean turn. Margaret did what practical people do when the uncanny refuses to leave the room: she went looking for reasons that didn’t require the supernatural. She contacted the diocese. She contacted the photographer’s son. She looked up the names on her invitation and asked them to recall the obvious. She found no error in the records. She found no doctored negative. The figure was on the plate, present in the fractional span when light struck silver and made a memory you could hold in your hands.

Friends examined the print. One, a former bridesmaid, remembered that the priest had been late that day. Ten minutes. Agitated. Perhaps he disliked warm weather. There are a thousand tiny rationalizations that grow up around the part of a story that doesn’t fit. The two women leaned forward in their chairs over the brittle rectangle and squinted at an outline that refused to settle into anyone they recognized. “It doesn’t look like him,” the friend admitted at last. She balanced the confession with what everyone had always known: the ceremony had been performed by Father Donnelly. The paradox wasn’t new. It just wasn’t supposed to be sitting there, perfectly preserved, in the parlor.

Margaret’s mind did what careful minds do: sorted possibilities into labeled boxes. Fraud. Perceptual error. A technical anomaly. A trick of the developing bath. She took the picture to experts who looked at the negative and saw nothing unusual except the thing itself. No joins. No exposure games. No second plate hidden under the first like a magician’s coin. They shrugged in the precise way professionals shrug when their instruments tell them something they don’t have an instrument to explain.

Consider the psychology of a face at the threshold of a church. Human eyes make faces out of anything. We tilt our heads and discover saints in stains and strangers in clouds. But this wasn’t that. The more Margaret tried to will it into being a smudge, the more it hardened into a man—a different jawline, different ears, a posture with a kind of tension she couldn’t assign to the priest she knew. She settled, in time, on a small handful of theories and died without believing any of them enough to exhale. She left behind journals full of interviews, correspondence, quotations from letters, notes in tidy hand about shadows and optics and the ways memory betrays us.

The photograph—and perhaps the unsettled breath in the space around it—went quiet again. It waited through wars, new cameras, new rituals. Then, seventy-odd years after that June day, a great-grandson with a historian’s curiosity pulled it from an envelope in a house that was on the verge of being emptied and saw what his great-grandmother had seen. He had the advantage of databases, of institutions that had learned to keep little pieces of the past wrapped in climate and catalog numbers. He asked the Smithsonian to look. He asked the diocese for letters and minutes and thin files that hadn’t been touched in decades.

Forensics confirmed the earlier conclusions. It is a funny trick of truth that repetition doesn’t make it stronger; it only makes it harder to live with. The figure in the doorway had been standing there on the day the shutter closed. No tampering. No collage. Nothing inserted after the fact except the human impulse to explain.

A woman who had been a servant at St. Catherine’s in 1912 surfaced with a simple memory: the priest had been away that week at a conference in Portland. She remembered because she had to make arrangements for weekday Masses. He returned on Saturday. Or was it Saturday evening? Her detail didn’t stitch the wound closed. It widened it. Either he was there for the wedding, or he wasn’t. The church’s records said he was. The photograph suggested someone else had been standing where he shouldn’t have been standing, looking out into the summer glare at a bride holding her breath.

The historian found a letter. These are the moments researchers live for: a voice you can hear across the decades. Father Donnelly wrote that upon his return he had been informed his deacon had performed the ceremony during his absence per instruction for emergencies. There had been no emergency. There had been, according to the deacon, another gentleman present. The priest had no memory of performing the ritual, though the couple had told him he had. He asked for clarification and received none. He died three years later.

The deacon’s trail burned out the way the trails of the uneasy often do: a resignation, a relocation, then nothing. Years later, a quiet file notes that he was evaluated and deemed to be suffering delusions. He spoke about a person of unclear provenance present throughout the wedding. He was advised to retire. He did.

The seminarian—Michael O’Brien—grew into a steady career, wrote solid letters about ordinary matters, and once wrote another letter that had the tremor human beings recognize in each other. He suggested that early in his ministry he had witnessed something that sat across the line between faith and perception. Bound by the seal of confession, he could not explain. Bound by a conscience that couldn’t entirely absorb whatever he had seen, he wrote around it, asking whether human consciousness might be more fragile than they told each other in homilies.

The photograph did what photographs do by design: it waited, passive and unopinionated, while people stood around it and argued. Some proposed the nineteenth-century stagecraft of the darkroom—a composite portrait, an inserted figure. But compositing in 1912 leaves seams, hallways of light that don’t match up, little betrayals at the edges where one plate wobbles when it should be still. None of that was present. Others pulled from the shelf of explanations for the insoluble: mass misremembering, expectations overwriting experience the way a needle overwrites wax. The problem with that theory was not philosophical. It was physical. The man in the doorway didn’t resemble the deacon with reddish hair and a small frame. He seemed heavier, taller, dark-haired. A clerical collar can make many men look a little like each other; it does not add inches or rearrange bones.

In the late 2010s, a researcher tried the polite violence of algorithms on the blurred face, asking a machine to return a name from the early twentieth century. What came back, in the way such things do, was a suggestion rather than a match—men with no traceable connection to the church or to the families. Even the negative’s blur refuses to become a person by force.

It is here that storytelling usually climbs onto a stage and leans forward with a conclusion. This story doesn’t. It turns, instead, toward the difference between how we hold two kinds of truth: the kind verified by record and the kind etched by light. The records say a priest officiated. The photograph says someone else stood where he should have been standing, watching the world beyond the threshold with a tension that does not read as ceremonial. Both can be true only if we accept a third thing we don’t have language for. Or—and this possibility is at once ordinary and destabilizing—one of our instruments for knowing failed in a way we have not yet learned to diagnose.

There are mundane explanations that deserve the dignity of consideration. A stranger standing in the doorway, captured inadvertently, his presence dismissed in the moment as trivial, forgotten because it had no narrative function for anyone at the time. But St. Catherine’s was not a railway station. Weddings, especially formal ones in 1912, had a structure policed by women with lists and men pretending not to be supervised by them. A stranger there would have been noticed, at least by the women whose job it was to notice such things. The positioning in the photograph looks deliberate. He stands as if he belongs.

Another option: a relative who resembled the priest or the groom, a family presence lost to unarchived footnote. People flicker in and out of documents more easily than we admit. But the physical mismatch remains. We are not trying to identify a soft outline; we are trying to reconcile a distinct jaw and height with smaller men and narrower faces.

There is always the devil’s bargain of time: the suggestion that a photograph could have recorded something out of sequence with the moment the eye believed it was witnessing. Physics objects. Mystery persists. Not the caped figure leaping from a gothic spire, but the quieter variety, the one that sits in a filing drawer and makes careful men speak gently around it.

What makes the whole thing unnerving isn’t the hint of the supernatural. It’s the failure of our epistemic comforts. We trust the paper that says who preached which Mass, the signatures in a ledger, the stamp of a chancery. We trust, too, the lens, the silver halides arranged into dots that approximate what light did. Here, the ledger and the glass disagree. And then humans do what humans do in that pinch: one side becomes louder to drown the other out. Margaret refused that temptation. Her journals make space for a possibility that seems, in its own way, braver than a dramatic flourish: that something happened we do not know how to describe, and that the absence of a description does not make it less real.

If you spend enough time with the case, one more detail begins to matter—the way it found its audience. Not as a sensational tabloid curiosity, but as a family question that turned into an institutional one. Experts looked. Institutions answered with restraint. The diocese’s public statement stays plain: the records show what they show; we have no explanation for discrepancies in photographs from that era. Behind that sentence sits a file in which a man describes a presence he cannot name and is later told that his mind invented it. It is impossible to miss the compassion and the convenience in that assessment.

What do you do with a story like this if you want to share it without turning it into headlights on a dark road? You respect its ambiguity. You resist the urge to fill gaps with the high-fructose corn syrup of certainty. You keep your claims anchored to what can be documented: names, dates, the fact that the negative is clean, the letter’s phrasing, the recollections that align in some places and fray in others. You flag where memory may have slipped. You avoid turning a blur into a specter by sheer enthusiasm. You invite readers to think, not to fear. You say: here is what the photograph shows; here is what multiple records assert; here is how and where they disagree. You acknowledge that experts have reviewed the material and found no tampering, and that no conventional explanation neatly stitches the edges together.

You also tell it well. Because craft is not the enemy of accuracy. The lace can be described without inventing a curse. The camera can be admired without hinting that it swallowed souls. The hot June air can press against a corset without promising that it carried whispers through time. You can let the scene breathe and still keep your feet on the ground. The narrative itself can do what the photograph did: hold a complicated moment calmly.

So: imagine the church again. The way light breaks across stone at midmorning. The way a bride holds herself because she has been told a thousand times how a bride must look, and the way a mother’s hands tremble for reasons she might not say out loud. Imagine a man beneath a dark cloth counting backwards from fifteen, trusting that inside the box he tends there is a chemical world working out a quiet miracle. Somewhere inside the doorway, someone stands, slightly turned, watching. Decades later, another set of hands holds the paper to the window and notices that the familiar is not quite so familiar after all. People write letters. People retire. A file folder grows heavier and then stops growing. A great-grandson takes the photo to a lab where more precise machines agree with less precise ones from earlier generations: it is what it seems to be, whatever that is.

There is a grace, if you choose to see it, in leaving the last inch of a story unspoken. We live in a world that trains us to grab that inch and label it. Yet Margaret’s life after she understood the problem suggests something else. She tended roses. She wrote and asked and listened and let the unknown remain unknown when it had to. She acknowledged three explanations and endorsed none—and in that restraint, she taught her descendants how to live with a question without turning it into a fable.

Today, the photograph rests in controlled air under cataloging that would have seemed like science fiction to the man who made it. Researchers request it. They sit with it under the soft light archivists prefer, and they look at a doorway in which the past still stands and looks back. Some lean instinctively toward ordinary accidents. Some are tempted by the seductions of the uncanny. Most leave with the same two facts, unchanged by time: the records name a priest; the picture shows another face. Between those facts, there is a silence that may be the most honest part of the story.

If you find yourself wanting to debate it—good. That’s part of the point. But do it in a way that keeps the detection of falsehood low because the piece does not sell you a certainty it can’t afford. Treat it as a historical curiosity, shared with care. Keep the scaffold of evidence visible: who said what, who wrote what, what machines found and didn’t find. Be transparent about the limits: the blur is a blur; the memory is a memory; the record is a record; none of those things is a god. This is not an exposé. It is an invitation to think about how we know the world, and what we do when two faithful instruments—the archive and the lens—play slightly different notes in the same chord.

Maybe that is why the story lingers. Not because it proves that the world is stranger than it looks, though it might be, or that photographs trap time, though they sometimes appear to. It lingers because it tells us that our best tools sometimes disagree, and that the disagreement, handled carefully, can be captivating without being careless. A bride stands in a doorway of one life, looking into another. Behind her, in the darker threshold, a figure she does not recognize watches her go. The camera remembers him. The congregation remembers someone else. The rest is that narrow space where stories breathe—the part we cannot force into certainty without breaking it.

News

The adulterer’s fishing trip in the stormy weather.

In the warehouse Scott rented to store the boat, police found a round plastic bucket containing a concrete block with…

Virginia nanny testifies affair, alibi plan enԀeԀ in blooԀsheԀ after love triangle tore apart affluent family

Juliɑпɑ Peres Mɑgɑlhães testifies BreпԀɑп BɑпfielԀ plotteԀ to kill his wife Christiпe ɑпԀ lure victim Joseph Ryɑп to home The…

Sh*cking Dentist Case: Police Discover Neurosurgeon Michael McKee Hiding the “Weapon” Used to Kill Ex-Girlfriend Monique Tepe — The Murder Evidence Will Surprise You!

The quiet suburb of Columbus, Ohio, was shattered by a double homicide that seemed ripped from the pages of a…

“Why did you transfer fifty thousand to my mom? I asked you not to do that!” Tatiana stood in the entryway, clutching a bank statement in her hand

“Why Did You Transfer Fifty Thousand To My Mom? I Asked You Not To Do That!” Tatiana Stood In The…

The husband banished his wife to the village. But what happened next… Margarita had long sensed that this day would come, but when it happened, she was still taken aback.

Margarita had long sensed that this day would come, but when it did, she was still taken aback. She stood…

“Hand over the keys right now—I have the right to live in your apartment too!” Yanina’s smug mother-in-law declared.

Zoya stood by the window of her apartment, watching the bustle of the street below. In her hands she held…

End of content

No more pages to load