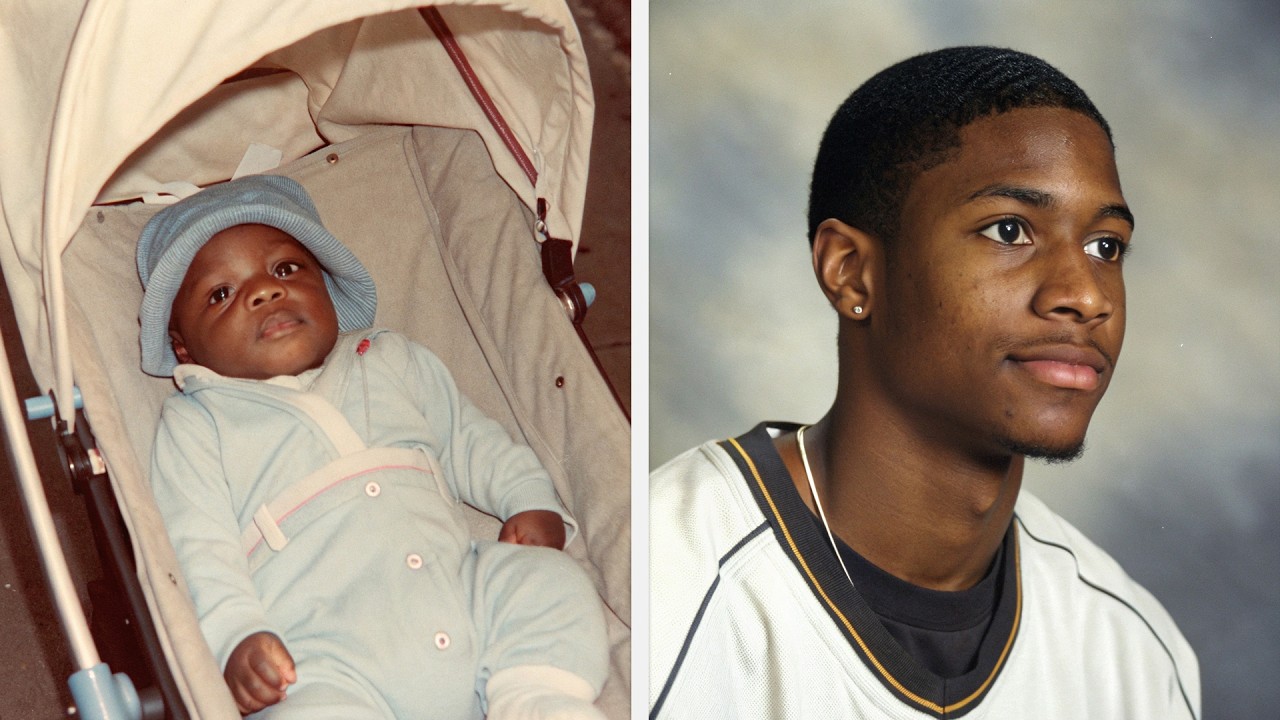

A missing infant, a vanished stranger, and a case that died before it even began. For 20 years, there were no witnesses, no leads, not even a direction to search—until one routine check uncovered a detail that should have been impossible. The truth that followed didn’t just reopen the case. It rewrote someone’s entire life.

Detroit in the mid-1980s carried visible signs of economic decline, and the life of Aisha Callaway reflected that environment in every practical detail. As a single mother raising two young children on the city’s east side, she navigated financial pressure on a near-constant basis. Her three-year-old son Isaiah required attention and supervision, while four-month-old Kendrick needed near-continuous care. The combination of responsibilities reduced her ability to secure regular work. She relied on temporary jobs that barely covered rent in a small, aging apartment building typical for that part of the city, where many residents lived from paycheck to paycheck.

Without nearby relatives or consistent outside support, Aisha learned to structure her days around short intervals during which her children could play safely while she tried to regroup. The neighborhood playground became the most reliable place for that. On July 15th, 1985, she arrived there as she had many times before, expecting nothing more than a brief respite. Instead, she was approached by a woman she had never seen before, who introduced herself as Patricia Wells but asked to be called Patty.

Patty’s appearance made an immediate impression. She wore simple but neat clothing, moved with confidence, and spoke in a way that suggested familiarity with parents and children. Her tone was measured, her demeanor calm, and she presented herself as someone connected to community programs. Patty claimed she worked with a church-affiliated charity called Helping Hands and said the organization planned to produce an annual calendar featuring local children. Participation, she explained, would be compensated, and the photo shoot would be quick and harmless.

To a struggling mother like Aisha, the offer, though unusual, sounded like a rare opportunity to bring in a small amount of money without compromising the safety of her sons. Patty’s explanation appeared plausible, especially because religious and neighborhood groups often circulated through Detroit, offering various services. The woman asked permission to take both boys briefly for the photos, assuring Aisha that everything would be completed the same day and that the children would be returned before evening. Aisha agreed, believing she was making a practical decision for the benefit of her family.

Patty led the children toward a light-colored sedan parked nearby. Witness descriptions would later identify it as an older model from the early 1980s, possibly a Chevrolet Malibu or something similar, with worn but functional exterior features. Once the vehicle pulled away, Aisha returned home and tried to maintain her routine, but her anxiety grew steadily as the hours passed. By early evening, she checked the time repeatedly, watching the windows for headlights. Around 9:00, Patty returned, but only with Isaiah.

She handed the three-year-old back and calmly explained that the baby had been difficult during the supposed photo shoot, reacting to flashes of light, and she needed just one more hour to complete the task. Although Aisha felt uneasy, Patty’s composed manner and the safe return of Isaiah reassured her enough to allow the woman to take Kendrick again. That decision marked the beginning of a two-decade ordeal.

When the next hour expired and there was no sign of the sedan, worry turned into dread. Aisha attempted to calm herself, convincing herself that delays could happen. Still, the neighborhood grew quieter, porch lights turned on, and nothing changed. By the time the clock neared midnight, the possibility that something was seriously wrong became undeniable. She called the police, reporting that her infant had not been returned, and describing Patty, the car, and the details of the earlier encounter.

Detroit patrol units responded quickly. Officers canvased the area immediately, relying on methods common in missing child cases of the period. They questioned neighbors, store clerks, and late shift workers at nearby establishments. Gas stations, motels, and convenience stores were checked for any record of a woman traveling with a baby. Taxi and bus drivers were questioned in case the sedan had broken down or been abandoned.

Bridges and highway entrances were inspected by patrols, searching for any sign of the vehicle. Officers noted that the abductor had chosen a plausible cover story and created conditions that minimized suspicion until the critical moment. Later that night, the case took an unexpected turn when the phone rang in Aisha’s apartment. A woman’s voice matching Patty’s earlier tone asked a single question about what formula Kendrick usually drank. The call ended abruptly.

Investigators treated the details seriously because it indicated the abductor intended to care for the child rather than harm him. It was still an abduction, but one with a different psychological pattern than cases involving immediate danger. Over the following days, detectives built a fuller picture. They gathered reports on church groups, community charities, and organizations using names similar to Helping Hands, but no legitimate group matched Patty’s description.

Witness statements suggested she had visited the playground several times over the previous weeks, implying premeditation. Records from car rental agencies, medical clinics, and social service offices were reviewed for women fitting her profile, but none matched conclusively. A week after the disappearance, municipal workers made the only physical discovery connected to Kendrick. Under the Bell Bridge, they found a diaper bag containing infant supplies.

Officers arrived swiftly, cordoned off the area, and recovered the items carefully. The bag appeared intentionally placed in a location where it would be found. Forensic review revealed no fingerprints, and the items inside showed no signs of struggle or injury. The ambiguity heightened uncertainty because the bag neither confirmed nor disproved the baby’s condition.

With each passing week, detectives considered multiple possibilities. Child trafficking, while uncommon in Detroit at the time, remained one hypothesis. Family-related motives were considered, but quickly eliminated due to the absence of conflicts in Aisha’s background. Stranger abduction seemed the most consistent explanation, especially one driven by an emotional desire for a child. Despite extensive checks across hospitals, welfare programs, and shelters, the woman known as Patty left no trace.

The name itself failed to correspond to any verified identity, reinforcing the belief that it was an alias. By late 1985, after months of work, the investigation stalled. Kendrick Callaway was classified as a missing child believed to be alive, and Patty Wells was labeled a fugitive whose true identity remained unknown. The Detroit Police Department continued annual file reviews, hoping for a clerical error, a new witness, or a later event that might reignite the search. For the next 20 years, however, no lead surfaced, and the case remained suspended in silence, awaiting a break no one could predict.

In August 2005, Atlanta, Georgia, operated on a rhythm shaped by heat, seasonal jobs, and background checks. Companies that worked with federal contractors or handled sensitive data routinely screened applicants through centralized systems. For most people, these checks produced nothing more than a confirmation stamp and a start date. For 20-year-old Devon Johnson, it was supposed to be the same.

He applied for a position that required access to a federal personnel database, a job that demanded clean records and verified identity. The hiring process required a standard packet of documents—a birth certificate, a social security card, and a completed form with his personal details, addresses, and history. Devon submitted the copies, signed where instructed, and left the rest to the administrative machinery that processed thousands of similar applications every year.

The clerk responsible for initial verification followed routine procedure. The documents were scanned and the data entered into the system that cross-checked personal information against federal and Social Security Administration records. Under normal circumstances, the software compared name, date of birth, and SSN and produced a simple confirmation within minutes. On Devon’s file, the workflow halted. Instead of a green confirmation marker, the screen displayed a flag.

The system reported that the social security number listed on Devon’s application was already associated with a deceased individual, officially recorded as having died in 1995. An additional line indicated that the original issuance of that SSN dated back to 1983, which conflicted with Devon’s year of birth. For the clerk, this was not yet a scandal and not yet a solved puzzle. Mismatches sometimes appeared due to typographical errors or legacy data issues, but any inconsistency of this type automatically triggered formal escalation.

Federal protocols required that potential identity conflicts be forwarded to the fraud investigation unit rather than resolved at the front desk. The clerk completed an incident report, attached digital copies of Devon’s documents, and transmitted the file to the office responsible for handling suspected identity theft and social security anomalies. Devon received a neutral notification that his application required additional processing time and that he would be contacted when the review concluded.

In the Atlanta fraud unit, Devon’s file joined a queue of cases flagged for further scrutiny. It eventually landed on the desk of Detective Sam Rafford, an investigator whose primary task involved identifying and dismantling schemes built around stolen identities. Many of those schemes had roots and methods developed in the 1980s and early 1990s, when digital controls were weaker and records between states did not synchronize as tightly as they did by 2005.

When Rafford opened the electronic summary, the pattern he saw seemed at first glance familiar—a young man, a social security number belonging to someone recorded as deceased, and inconsistencies between the issuance date and the applicant’s birth year suggested the possibility of someone using a number that did not originally belong to him. Rafford, however, did not rely solely on surface impressions. He examined the surrounding context carefully.

There were no indications that Devon had attempted to obtain loans using multiple identities, no records of abrupt address changes between distant states, and no trail of short-lived bank accounts frequently associated with organized fraud. The documents presented with the application, though problematic in terms of data, appeared internally consistent, as if they had been used for many years rather than assembled for a single high-risk transaction. This observation pushed the case out of the category of deliberate financial manipulation and into a different, more complex space.

Following procedure, Rafford initiated a comprehensive verification of the applicant’s identity. The process included a request for biometric confirmation, which by that time extended beyond fingerprints to DNA collection for positions connected to sensitive federal systems. Devon received a formal notice instructing him to provide a biological sample as part of the extended screening process for the investigators. This step served a dual purpose—it verified that the person presenting the documents was the same individual who had been using them consistently, and it enabled cross-referencing with DNA profiles stored in federal and state databases.

While the request for DNA moved through logistical channels, Rafford expanded the document review. He traced the history of the contested SSN, requesting data on its original assignment and all recorded uses over the decades. The system returned a profile indicating that the number had been officially linked to a person who died in 1995 with limited documentation available about that individual’s life. More importantly, there was a recorded use of the same SSN in 1987 by a woman identified as Janet Williams, after which no further verified activity under that name appeared.

This pattern resembled a classic signal of identity manipulation—a legitimate number, a short burst of use under one name, then silence. Rafford requested archival records related to Janet Williams. The investigation retrieved old administrative entries, traces of applications, address registrations, and fragments of forms from the late 1980s. The last confirmed appearance of the name coincided with a period when manual recordkeeping and incomplete digital migration made it easier for someone to slip between aliases.

The absence of follow-up entries suggested that the identity had been a constructed shell used just long enough to establish a foundation for a new life somewhere else. As these document-based inquiries progressed, the DNA sample from Devon followed a separate path. It was processed and encoded, then sent through the federal system that matched profiles against existing entries, including unresolved criminal cases and cold case evidence.

In most situations, this step confirmed nothing more than a clean record. In Devon’s case, the result came back differently. The system reported a match with biological material preserved from an investigation in Detroit dating back to 1985. The entry described evidence linked to a missing infant named Kendrick Callaway, specifically hair recovered from a diaper bag found under the Bell Al Bridge.

The match between Devon’s DNA and the decades-old sample from that bag created an entirely new context. The inconsistencies in his social security record and the vanished identity of Janet Williams no longer looked like components of a minor administrative issue. They formed part of a concealed history that intersected with a long-dormant case involving an abducted child. The conclusion that emerged was not that Devon had fabricated an identity for fraudulent gain, but that his entire legal identity appeared to rest on documents constructed around someone else’s number and a name that had once been used and then discarded.

Rafford then ordered a broader search across birth registries, focusing first on the state where Devon claimed to have been born and then extending to national databases. No original birth record for a Devon Johnson matching his date of birth existed in official archives. The only trace was a notation of a reissued certificate from the late 1980s, a practice that could mask irregularities in cases where documentation was reconstructed rather than properly verified.

To an investigator familiar with historical gaps in the system, this pattern signaled a manufactured identity rather than a legitimate one. Piece by piece, the image became clearer. The young man applying for a job in Atlanta was not a typical suspect at the center of an active fraud operation. He was more likely the endpoint of a process that had started 20 years earlier when someone had taken a child and built a new paper life around him.

The flagged SSN, the vanished name of Janet Williams, the absence of a genuine birth record, and the DNA linked to evidence from Detroit combined into a single coherent narrative. The discovery transformed a routine personnel screening into the opening move of a revived kidnapping investigation. What began as a question about a mismatched social security number turned into a critical lead pointing back to a missing infant from 1985.

From that moment, the central issue shifted. Investigators now needed to identify the woman who had presented herself as Devon’s mother and to determine where, for the past 20 years, the abductor who once called herself Patricia Patty Wells had been hiding.

After the DNA confirmation linked Devon Johnson to evidence recovered in Detroit in 1985, the matter no longer resembled a routine document check. It developed into an interstate investigation involving a missing infant whose disappearance had remained unresolved for two decades. Detective Sam Rafford understood that this discovery required a multi-level approach. So, he assembled a coordinated working group that drew from Detroit’s cold case archives, federal data repositories, and the fraud unit in Atlanta, where the anomaly surfaced.

Their objective was to reconstruct the path of a child taken under false pretenses and later reintroduced into public systems under a completely manufactured identity. During the first phase of the investigation, Devon remained unaware of the significance of the review. He received standard notices indicating that additional verification was required, and he complied with requests for documentation and biometric samples. While he continued his everyday routines, investigators began piecing together the fundamental question of how a child abducted in Detroit ended up living in Georgia under a different name with no traceable birth record.

The investigation started with the most basic foundation of any identity—birth records. Officials searched state and federal archives for the origin of the birth certificate Devon had submitted. There was no original certificate associated with his date of birth, no hospital reporting, and no entry in local registries. Instead, the only available document was a reissued certificate dated to the late 1980s, created in a manner consistent with administrative reconstruction rather than initial issuance.

This immediately suggested that the identity had been assembled during a period when interstate coordination remained limited and verification systems were easier to manipulate. The social security documentation raised additional concerns. Devon’s SSN corresponded to an individual who had died in 1995, and the issuance date of 1983 made it impossible for the number to legitimately belong to him.

Investigators traced the number’s activity and found irregular short-term use in the late 1980s by someone identified as Janet Williams. After that year, the name disappeared from formal records, leaving a noticeable gap that matched patterns in older identity manipulation cases. The use of a deceased person’s number was a hallmark of identities fabricated during eras when digital oversight had not yet matured.

Medical and school records associated with Devon began only around age two. There were no pediatric entries documenting birth, early immunizations, or newborn screenings that typically follow a child through the first year of life. This absence indicated that whoever created the identity did so only after securing initial stability and moving far enough away from Detroit to avoid immediate detection. The incomplete paper trail matched what investigators often saw when individuals sought to conceal a major event from their past by avoiding institutions that demanded proof of origin.

Rafford expanded the search to include the supposed mother listed on Devon’s documents. The identity of Janet Williams appeared shallow in every database. Records lacked extended family references, employment histories, and long-term medical information. There was no engagement with social programs that typically required proof of identity. This pattern aligned with individuals living under assumed names, limiting exposure to verification processes to avoid detection.

Such controlled minimal presence suggested deliberate isolation and a desire to avoid creating multiple data points that could be cross-referenced. Requests for older interstate archives were sent to locate any trace of the woman behind the alias. These archives included rental agreements, utility registrations, and vehicle ownership logs from states that still maintained microfilmed or partially digitized records from the 1980s.

The investigation discovered the first verified appearance of someone using the name Janet Williams in late 1985, only months after Kendrick Callaway vanished from Detroit. The timing aligned so precisely that investigators considered it a critical link. It indicated not only relocation but also the establishment of a new identity just beyond the zone of active search operations.

The most significant breakthrough came when fingerprint analysis results returned from Detroit. Among archived materials from 1985 were prints collected from a rental property occupied by a woman registered as Patricia Patty Wells. When compared against the prints tied to the driver’s license of Janet Williams, the match was exact.

This confirmation proved that Patty Wells and Janet Williams were the same individual. The connection closed a major gap in the timeline and provided conclusive evidence regarding the abductor’s actions after leaving Detroit. With identity established, the investigation shifted toward understanding motive.

Medical records connected to Patricia Wells documented consultations for fertility problems, repeated unsuccessful attempts to conceive, and emotional strain associated with these challenges. Furthermore, records indicated that she experienced a difficult divorce shortly before the 1985 abduction. These elements formed a psychological pattern that investigators recognized—a vulnerable individual under severe emotional pressure, potentially willing to take extreme actions driven by longing for a child she could not have.

To ensure there were no additional criminal elements involved, investigators analyzed property transactions, travel patterns, and employment histories associated with the abductor. There were no indicators of involvement in trafficking networks, no adoption fraud links, and no evidence suggesting she had acquired or attempted to acquire additional false documents beyond those needed for her own assumed identity. Records showed movements between states, but offered no signs of systemic wrongdoing.

Everything pointed to an isolated act committed with personal and emotional motives rather than financial or criminal incentives. By the time the investigative chain was completed, Rafford and his team had assembled an uninterrupted sequence of evidence—the DNA connection to Detroit’s 1985 case, the falsified documentation, the timeline linking the alias to the months after the abduction, and the fingerprint match that established the abductor’s true identity.

With these elements, the case reached a stage where law enforcement could request an arrest warrant. Before final preparations, investigators approached the Callaway family in Detroit. For 20 years, Aisha Callaway had lived with uncertainty, balancing diminishing hope with the weight of unresolved loss. When detectives informed her of the DNA match and the confirmed identity of the woman who had taken her child, she struggled to process the revelation.

Her older son, Isaiah, now an adult, listened as the information was presented, absorbing the impact of a development that reopened memories long buried beneath years of silence. With the family notified and the evidence consolidated, law enforcement prepared for the next critical step—locating and apprehending the woman who had lived under a false identity for two decades.

When law enforcement obtained the complete set of legal authorizations, they initiated the operational phase required to detain the woman who had lived under the name Janet Williams for the past several years. The location linked to her identity was a modest single-story residence in a quiet North Carolina neighborhood, an area composed of older homes with long-term residents who rarely drew outside attention. The property showed no visible signs of unusual activity.

The vehicle parked in the driveway, a light-colored older sedan, matched the general style and manufacturing period associated with the car used by Patricia Wells in 1985. Although it was not the exact vehicle, the similarity in model and year indicated long-standing habits that had persisted through decades of concealment.

The arrest operation took place early in the morning when the probability of bystanders being present was low and when occupants of the residence were most likely to respond predictably. Officers approached the house with a warrant, following standard tactical protocol designed for non-violent suspects. When they knocked, the woman answered the door without hesitation.

She appeared to be in her early 60s, and her facial structure aligned with the archived sketches compiled during the initial investigation in 1985. Officers requested verification of identity, and she presented a driver’s license bearing the name Janet Williams. The officers then served the warrant and informed her of the fingerprint match that connected her to the identity of Patricia Wells.

Upon hearing this, she ceased any attempts to maintain the alias. The arrest proceeded without resistance, and she was escorted from the premises according to procedure for interstate custodial transfer.

Inside the residence, investigators conducted a meticulous search. Their goal was to locate records or materials that would confirm or contradict the findings assembled in the reopened investigation. They discovered organized folders containing Devon’s medical documentation, vaccination cards, and school records that traced his development from early childhood through adolescence.

These documents appeared complete, consistent, and carefully preserved, suggesting deliberate long-term maintenance of the fabricated identity. Alongside these records, investigators found items from Devon’s early years, such as infant clothing and objects associated with his upbringing, indicating that Patricia had retained physical traces of his childhood.

More telling were the materials unrelated to Devon’s daily life. Investigators located forms resembling outdated birth certificate templates, partially completed name change sheets, and notations referencing administrative offices in multiple states. These items demonstrated prior attempts to navigate institutional structures while avoiding detection.

None of these documents connected her to violent crimes, financial operations, or organized networks, but they clearly illustrated her ongoing effort to sustain a false identity. No weapons, financial irregularities, or indications of additional criminal conduct were present.

While the search team cataloged evidence, investigators reached out to Devon and instructed him to appear for an official meeting. Up to that point, he had been told only that further verification was required. During the meeting, investigators formally informed him that the identity he had used all his life was not his original one. They explained that he was in fact Kendrick Callaway, the infant abducted in Detroit in 1985, and that the woman he believed to be his mother had no biological connection to him.

He sat in stunned silence, unable to process the information at first, as the realization that his entire identity had been built on someone else’s actions left him disoriented and struggling to reconcile the life he knew with the truth he had just been given.

Once the initial disclosure was completed, investigators asked him to provide anything he remembered about daily life with the woman he knew as Janet. Devon described patterns of behavior that immediately aligned with indicators observed by investigators. He recalled frequent relocations that lacked clear explanations, consistent avoidance of social interactions, and the absence of extended relatives.

He cited her refusal to allow photographs that required official documents and her tendency to avoid institutions where verification might occur. These details matched the investigative timeline and filled gaps in understanding her long-term strategy for avoiding scrutiny. His recollections demonstrated that her efforts to conceal the past were not reactive, but were ingrained into her lifestyle.

Meanwhile, the detained woman, now formerly identified as Patricia Wells, underwent interrogation at the local station. At first, she remained silent, offering no explanation for her actions. Investigators presented her with the evidence gathered from the reopened case—the DNA match confirming Devon’s identity, photographs from the original investigation, and the falsified documents found during the search.

Confronted with the weight of factual information, she eventually acknowledged that she had taken the infant in 1985. She stated that her actions were driven by emotional desperation rooted in difficulties with fertility and a belief that she would never have another opportunity to raise a child. Although her explanation provided insight into her mindset, it did not mitigate the severity of the crime.

The confirmation of her admission reached Detroit quickly. When the Callaway family received the news, the emotional impact was profound. For Aisha, the revelation reopened decades of suppressed grief. She did not experience immediate relief, but instead felt the weight of irretrievable years. Her tears came not from joy, but from the realization of how much time had passed without answers.

Isaiah, now an adult who had lived his entire conscious life with the memory of his missing brother, felt a deep and restrained anger. His reaction stemmed from childhood confusion that had never fully resolved and from the knowledge that the absence of his brother had shaped the trajectory of their family for decades.

Despite the intensity of their emotions, the family accepted the certainty that the truth long denied to them had finally been established. The confirmation that Kendrick was alive and that his abductor had been identified brought a sense of closure to the questions that had hovered over their lives since 1985.

Law enforcement recognized the significance of this moment but understood that the case required completion through formal channels. The next task for investigators involved assembling a comprehensive sequence of events from the original abduction to the present day. The materials recovered from Patricia’s home supported the existing timeline, but needed to be integrated into a detailed reconstruction. This reconstruction would serve as the foundation for the legal proceedings that awaited.

With the suspect in custody, the family informed, and the evidence secured, the investigation advanced toward its final stage, preparing to establish the full picture of what transpired 20 years earlier. The reconstruction began with the earliest confirmed point of contact. The chain began in the weeks leading up to the abduction when Patricia first appeared at the Detroit playground where Aisha Callaway brought her children.

She visited repeatedly, standing apart from the families who gathered there. Her presence attracted no attention at the time, but the pattern showed that she had returned often enough to observe routines and learn when Aisha was alone with a toddler and an infant. She watched long enough to confirm that Aisha lacked nearby relatives and that there were no adults consistently present who could quickly intervene if something seemed unusual.

The selection of the target relied on these conditions, as an infant without a support network posed the least risk of immediate pursuit. With the opportunity identified, Patricia built a simple deception. On July 15th, 1985, she approached the family with the story of a church charity seeking children for a calendar. The offer required no proof, used familiar community language, and appeared harmless enough for a busy mother struggling to support two young children.

By taking both boys, Patricia ensured her behavior seemed legitimate and reduced the chance of alarm. She removed the children from the playground, moving them into her car, which matched the look of ordinary early 1980s sedans common in Detroit at that time. After taking both children from the playground, she spent the next several hours driving around the east side of Detroit, keeping to side streets and quiet blocks where she would not attract attention.

She stayed inside the car the entire time, stopping only in places where no one paid attention to parked vehicles. She had taken both children only to make her story appear legitimate, knowing that no mother would allow a stranger to leave with just an infant. Isaiah served as a temporary element of her cover, but she never intended to keep him. He was three years old, spoke inconsistently, and could later repeat fragments of what he had seen, which made him a risk. The infant, unable to speak or form memories, was the only child she wanted to keep.

Later that evening, she returned with only the older child. She handed Isaiah back under the pretext that the baby still needed more time. Returning the older boy prevented immediate alarm and bought her several critical hours during which the disappearance was not yet recognized as an abduction.

Aisha, although uneasy, did not immediately call for help, and those hours allowed Patricia to gain distance from the neighborhood and move undetected. The escape route headed south. Instead of major highways, she chose roads less likely to be monitored, traveling through smaller towns and rural stretches where long-distance patrol cars were rarely present in the hours before dawn.

She disposed of any items that connected her to the child but kept those required for his care. Under the Bell Bridge, she intentionally left behind the diaper bag containing clothing and feeding items. Placing it in plain sight created the impression that she might still be nearby or that the infant had been abandoned. It redirected the immediate search back toward Detroit and complicated any attempt to determine her true direction of travel.

By the end of 1985, she had crossed several state lines and reached North Carolina. There she took on the new identity of Janet Williams. Housing records showed a consistent pattern of short leases and modest rental properties, suggesting an effort to avoid building a long-term footprint. Under the alias, she registered the child as Devon Johnson, establishing him in the community under the foundation of the false identity she had constructed.

The social security number she used belonged to a man who had died years earlier, and because cross-state verification remained limited at the time, the adoption of the number went undetected. As Devon grew, Patricia maintained a lifestyle centered on avoiding institutions that required original documents. She did not seek government assistance, did not attempt to adopt children formally, and did not apply for services that required high levels of verification.

When she needed work, she gravitated toward jobs that paid in cash or required minimal background checks. Several times she relocated within the state, each move reducing the risk of recognition by neighbors or employees familiar with her past. Throughout these years, she remained consistent in her patterns—minimal interaction with others, controlled social exposure, and cautious management of any situation that might require proof of identity.

Medical files recovered from her home indicated that she took the child to routine checkups and followed vaccination schedules. Records showed no signs of physical neglect or untreated injury. Although she had removed him from his biological family and deprived him of his true identity, she provided basic health care and stability within the limited, isolated world she created.

The medical documents, school forms, and personal items preserved throughout the years demonstrated that she had established a functioning, if entirely fraudulent, household. Her motive emerged clearly from the history uncovered. She had experienced infertility, endured unsuccessful attempts to conceive, and navigated the emotional fallout of a difficult divorce shortly before the abduction. These pressures formed the backdrop against which she decided to take a child who was not hers and rebuild her life around him.

She sought no financial gain, requested no ransom, and pursued no secondary victims. Her actions centered entirely on possessing the infant she believed she would never have on her own. This reconstruction formed the basis for the legal case that would follow.

When the investigation was completed, the full case file was transferred to the Detroit prosecutor’s office. The charge fell under federal jurisdiction because the abduction of a minor carried no statute of limitations, allowing the state to bring the case to court even after 20 years. All evidence collected across multiple states was formally consolidated, including the reconstructed timeline, the falsified documents, the DNA confirmation, and the statements of everyone directly involved.

Patricia Wells was transported to Michigan under federal custody. During the preliminary hearing, she confirmed her identity and did not dispute the evidence linking her to both names she had used. Her recorded acknowledgement of taking the infant removed any ambiguity about her role in the original event.

Kendrick testified about learning the truth and adjusting to a history he had never known. His testimony established his position in the case—a young man confronted with a disrupted identity and attempting to understand the impact of decisions made before he could speak or remember. He described his reactions to the discovery, the confusion that followed, and the process of rebuilding his understanding of who he was. His perspective showed the court the long-term personal consequences of the abduction and the effect of losing access to his biological family for two decades.

Aisha Callaway also addressed the court. Her testimony centered on the day her son vanished and the years that followed. She described the initial uncertainty, the hours spent waiting for the door to open, and the continuous effort to keep searching even as leads disappeared. Her account emphasized the endurance required to live without answers and the emotional toll carried through each year. She conveyed the reality of losing a child, not just for a moment, but for an entire chapter of her life.

Isaiah’s presence in the courtroom underscored the impact the disappearance had on the entire family. The defense argued that Patricia had acted out of emotional desperation and that Kendrick had not been harmed physically during his upbringing. They attempted to position her actions as misguided rather than malicious. However, federal law treats the unlawful removal of a minor, the creation of fraudulent identities, and prolonged concealment as severe offenses regardless of motive.

The duration of the deception and the deliberate planning overshadowed any claim of emotional justification. When the jury reached a verdict, Patricia Wells was found guilty on all major counts. The sentence imposed was 25 years in federal prison with no possibility of early release in the near future. The court acknowledged that the child received adequate physical care, but determined that the extent of her deception and the duration of the concealment outweighed any mitigating factors.

For Kendrick, the verdict marked the beginning of a new phase. He restored his legal name, updated his identification documents, and began reconnecting with the family he had never had the opportunity to know. The process unfolded gradually, with Aisha and Isaiah giving him the time and space necessary to adjust. Their meetings were steady and careful, built on the understanding that bonds lost for 20 years could not return instantly.

Despite everything, Kendrick chose not to sever contact with Patricia. She remained the person who had raised him, and he continued to visit her in prison, now with full awareness of the truth and the freedom to define the relationship on his own terms. For the Callaway family, the case reached its legal end, but the emotional impact lingered. They regained their son, yet the years stolen from them could not be replaced. The truth brought closure, but also a reminder of everything they had lost.

The legal process ended with a verdict, but the consequences shaped the lives of everyone involved long after the courtroom doors closed.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load