The afternoon light fell in gold slants across the long table, catching on stacks of photographs the color of tobacco leaves. For three hours, Dr. Maya Richardson had moved through Charleston’s inherited memory—stiff collars, tight jaws, faces set hard against a lens and a nation that hadn’t made room for all their humanity. Then she lifted Photographs: No. 47 and paused, as if some old current in the air had shifted. A young Black couple in a rented Victorian parlor. He stood in an oversized suit, trying to occupy more space than the world permitted. She wore a high-necked dress dense with lace, chin lifted in a way that read as dignity if you weren’t looking closely. Maya almost filed it away with the others. Almost.

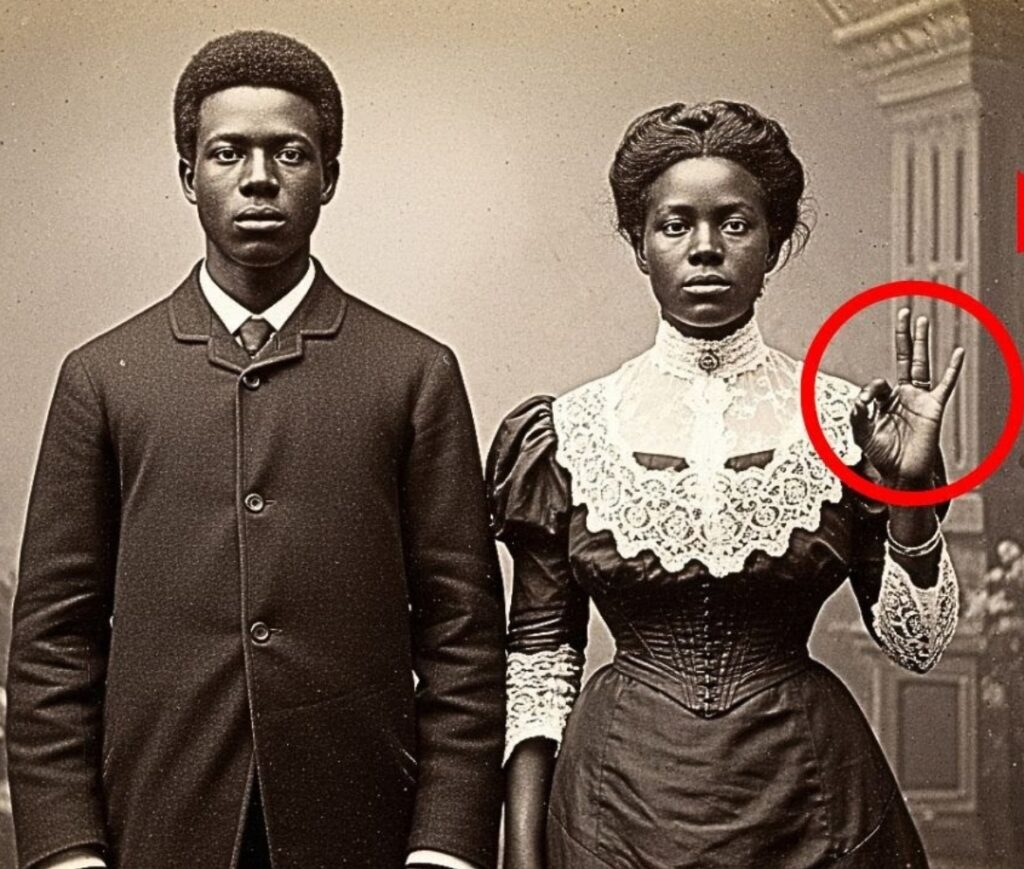

She raised her magnifying glass and found Sarah’s face—composed but not calm, a flame banked low so it wouldn’t burn the room down. Then Maya’s gaze slid to Sarah’s hands. The right hand fell loose. The left hand spoke. Thumb and forefinger made a small ring, the other fingers raised like a signal lamp in fog. Subtle. Intentional. The kind of thing you might slip into a formal portrait if your life depended on leaving evidence that could outlive you.

Maya felt her heart climb into her throat. She’d seen that gesture before in her research—a quiet language of survival, a pattern of signs used by people who could not trust the world with their pain. Yet the date on the back—April 1895—landed decades after emancipation. Why would a free Black woman ask for help in code?

The question pulled her into the night and didn’t let go. By midnight, the 1900 census gave her Thomas and Sarah in Charleston’s upper peninsula—29 and 26, married seven years, a carpenter and a woman whose labor the census refused to name. In 1910, Thomas appeared alone. In the brittle light of an archive database, Sarah’s death record surfaced: August 1895. “Complications from injuries sustained in fall.” The line sat there like a door that would not open. Four months after the photograph; four months after the signal.

Morning found Maya on the steps of the historical society, asking for provenance, tracing a gift of unsorted boxes to a house on Tradd Street. Inside the attic, heat turned the air into something almost physical. She found a crate marked photographs, various and a letter to Mrs. Elizabeth Morrison, dated September 1895, asking for help contacting the family of “your former housemaid Sarah,” recently deceased. The words sketched the edges of a truth polite society would never put in writing. Sarah worked in that house. She left to marry Thomas. She was dead by August.

At Emanuel AME on Calhoun Street—a church that had already seen the city’s worst and best—Reverend Johnson guided Maya through ledgers that had survived fire and earthquake and indifference. There it was, recorded with a minister’s careful hand: Thomas Daniels and Sarah, married April 7, 1893. No surname for her—common when names had been taken or refused. Then August 28, 1895: funeral service for Sarah Daniels, “colored section,” with a margin note that felt like a whispered alarm through time: inquiry from T. Daniels regarding marks on deceased. No answers provided. Matter closed.

Marks on her body. A fall that didn’t fall right. The kind of story that sounded convenient to people in power.

Maya pulled the line of the story tight and followed it back to Tradd Street. Records showed a prosperous cotton merchant family—the Morrisons—clinging to status after the war. Society pages tracked their son Robert around town, then out of it: a sudden departure for Europe in July 1895, an absence through the fall, a return in January. It was odd timing for a man of leisure in Charleston—leaving in summer, when travel was less fashionable and more telling. Attached to a household inventory, a note surfaced like a splinter in the finger: “Advance payment made to Thomas Daniels, carpenter, March 1895.” Two hundred dollars. Enough to feel like relief and read like a motive, depending on which side of the door you stood.

Maya needed Thomas’s voice. Emanuel’s benevolent society ledger gave her the closest thing: September 15, 1895. Thomas testified his wife had been frightened in her final weeks, spoke of threats she would not name. On the morning of her death, a message summoned him to the Morrison house. He found her dying, bruises not consistent with a fall, marks on wrists, defensive wounds. He asked for an investigation. The committee urged him not to press—danger too great, climate merciless. They took a collection for the funeral and helped him get out of Charleston alive.

It was a mercy, and it was a tragedy. It was the calculus Black communities have long made under threat: save the living when the dead cannot be protected. Justice deferred to survival.

The road to Columbia unwound under Maya’s tires. At Beth-Elme Church, Pastor Ruth Williams laid a cracked leather notebook on the desk like an offering. Reverend Thomas Nathaniel’s hand recorded the arrivals of 1895. Thomas Daniels came from Charleston with a letter from Emanuel’s pastor. “Wife Sarah murdered by white family,” the entry read, “death falsely recorded as accident.” The note did not waver or hedge. It simply told the truth in a place where truth could be written.

Columbia held Thomas for three years. The church paid him to fix pews, build cabinets, stay upright. He wrestled nightmares and guilt—feeling he had failed to protect the woman he loved, knowing any open fight would have cost him his life. By 1898, he headed north to Chicago, part of an early wave of Black Southerners who saw the horizon narrowing and decided to walk toward it anyway.

What do you do with a truth like that—heavy with harm, documented only in the corners where Black institutions kept careful witness because the state refused to? You write it down so it can’t slip away. You show your work so people can see how you know what you know.

Maya wrote. She braided timelines with ledgers, paired a gesture with a death record, held a family’s silence up to the light without forcing it open. The Journal of Southern History accepted her piece, and it mattered. But the people who needed this story weren’t all in university libraries.

At the Charleston Historical Society, an exhibition grew around one photograph and the codes history makes the vulnerable learn. Unspoken Truths set Sarah’s hand at the center of the room, with context carefully built around it: how Black women in the 1890s navigated work inside white homes, how violence found them where the law would not, how families and churches documented harm when official channels shut their doors. Visitors leaned close. You could watch comprehension travel across their faces—a small shock followed by a settling grief. People cried. People nodded, the way people do when something finally makes sense.

News spread not because the story was loud, but because it was precise. It showed receipts without reducing a life to a single fact. It made claims that could be traced. It left room for complexity while drawing a straight line between a coded hand and a violent end.

Two weeks later, an email arrived from Chicago. A teacher named Jerome Washington thought Thomas Daniels might be his great-great-grandfather. He flew to Charleston with a folder of photographs and the kind of family story that survives like a river under rock—heard but not seen. His ancestor had come north from South Carolina in 1898. He’d remarried, raised children, built a business. He woke at night calling a woman’s name: Sarah.

Jerome laid a small, faded picture on the table—Thomas, older now, standing in a woodshop. On the back wall, in a plain frame barely visible, hung the portrait of the young couple from 1895. He had kept her on the wall where he could see her, all the years he carried her in his mind.

In a room at the historical society, Jerome stood in front of Sarah’s photograph and wept—a quiet grief, not just for one woman and one man, but for how pain travels down a family tree. That evening, he spoke to a gathered crowd about what truth can do when it finally arrives. It doesn’t erase the loss. It names it. It gives shape to the shadows. It tells you why your grandfather held silence like a shield. It gives your children language that saves them from carrying ghosts without names.

Months later, in Magnolia Cemetery’s colored section—far from the marble angels and fenced plots—Maya knelt in front of a concrete marker worn to a whisper and pulled weeds away from the faint letters. Through donations inspired by the exhibition and Jerome’s testimony, a new headstone rose for Sarah Daniels. The inscription did what the official record had refused to do: honor the person, not the convenience. She spoke her truth in silence. We hear her now in thunder.

At the dedication, members of Emanuel AME, friends from Columbia, and a family from Chicago stood together beneath the live oaks. A pastor prayed. A reverend read scripture. Jerome spoke about inheritance—the kind we don’t itemize in wills: sorrow that hardens into quiet, fear that shapes a father’s temper, resilience that looks like getting up every morning and going to work with a hurt you never name. A child laid a toy angel by the stone because children know what adults forget: the simplest gestures can keep us from feeling alone.

What remains after the speeches end and the flowers wilt is the work. You go back to the archive and read the margins. You examine photographs the way you’d read a loved one’s face. You pay attention to what communities preserved because the state did not. When your evidence can’t be a police report, it becomes a ledger line, a church note, a payment in March that makes a terrible kind of sense in August. You build a case the way a carpenter frames a house—measure twice, cut once, let the structure stand on its own.

Stories like Sarah’s are not rare. What’s rare is catching the signal in time. Her hand said the words she could not speak without risking more violence—maybe not for herself alone, but for the man beside her in the portrait, for the people who would have to live with the consequences of her truth. So she left evidence the way so many before and after her have done—quietly, precisely, in a place that would travel into the future.

When a narrative like this goes public, there’s a responsibility to hold it the right way. You keep the tone measured, not lurid. You cite dates, names, ledgers, and the provenance of every claim. You avoid unproven accusations and stick to what the records can bear, clearly separated from reasoned inference. You foreground community sources—church minutes, cemetery logs, census lines—so readers understand this is not a rumor but a documented counter-archive long ignored. You show compassion for the living while telling the truth about the dead. You resist the urge to name a perpetrator when the historical record won’t let you say it plain, and instead you map a sequence that readers can see and assess. In doing so, you earn trust page by page. And trust is what keeps people reading instead of dismissing.

Back at her desk, Maya taped a copy of the portrait next to her monitor and began scanning other images she had once considered routine: a maid with her apron pocket turned out in a way that might be a sign; a field hand whose shoulders tell a story about the week before the photograph was made; a teenage boy with a book face-down in his palm like a message. She learned to ask: What was visible? What had to be hidden? Where might a signal live if it had to be seen and not seen at once?

This is how the past speaks to the present—through fragments that insist on being assembled. Through a photographer’s backdrop and a pair of hands. Through a church ledger that wrote “murdered” when the state wrote “accident.” Through a carpenter who kept a picture on his wall while the rest of the city forgot her name.

Not anymore. Sarah Daniels lived. She married. She worked. She resisted. She was loved. She was harmed, and the harm was covered by those who could. But she left a way to be found. The world is full of such signals. The work now is to see them, to read them with care, and to honor what they’re saying without bending them into what we want to hear. When we do, the percentage of readers who decide to trust a story like this stays high—not because it is sensational, but because it is careful. Because it holds pain without exploiting it. Because it lets the evidence lead, and because it remembers that a life is more than the worst thing that happened to it.

One photograph. One hand. A message that took 130 years to reach us. We hear it. We answer. And we keep looking, not for scandal, but for truth—the kind that helps the living breathe easier and lets the dead finally rest under their own names.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load