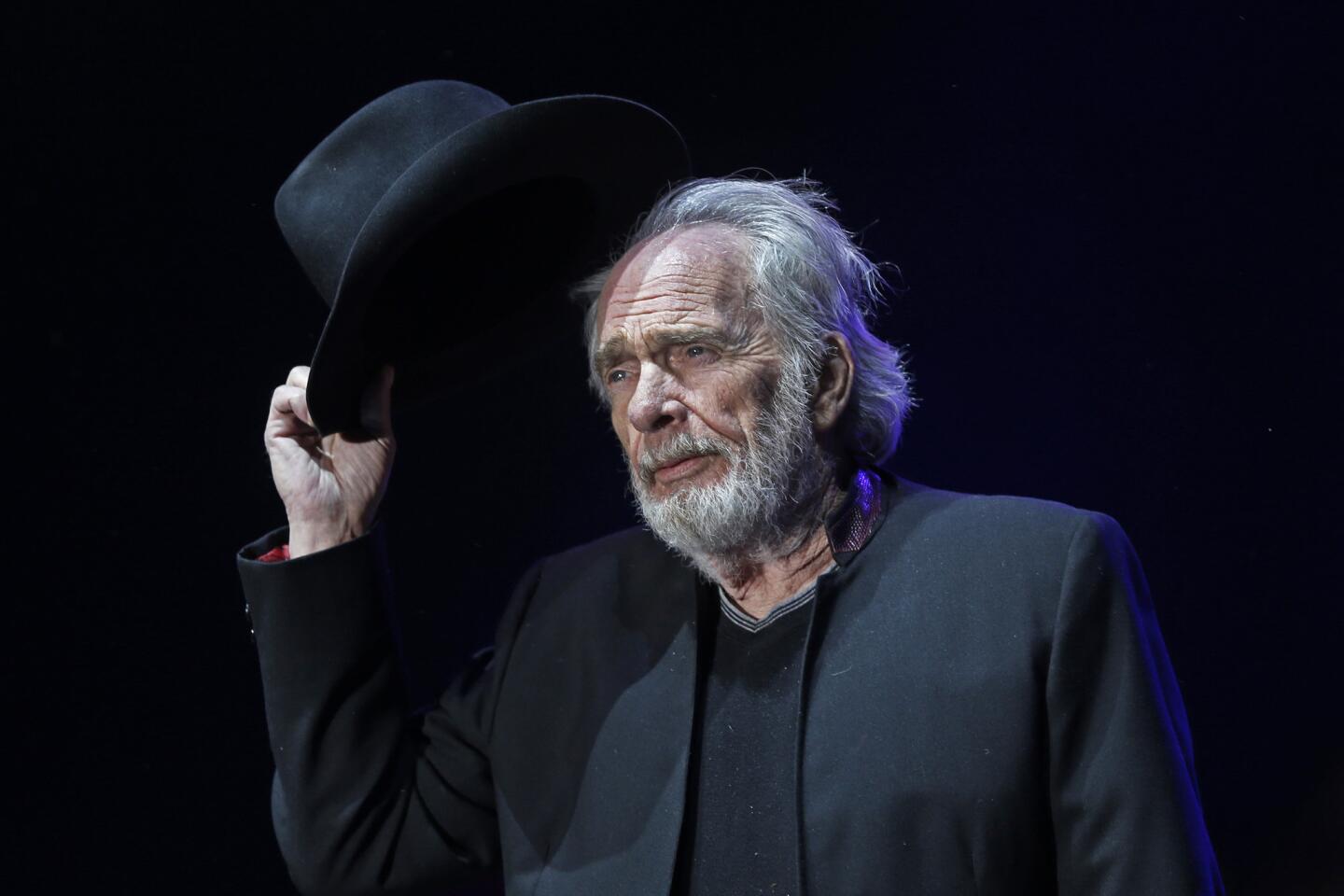

When Merle Haggard first heard the question—was it true that he had watched Johnny Cash perform as a prisoner in San Quentin?—he answered without hesitation: “That was true.” The story, already a piece of country music folklore, is not only true but more fascinating and layered than most fans realize. It’s a tale about transformation, music’s power behind bars, and how a rebellious young man on the wrong side of the law found his path to country legend.

On New Year’s Day, 1958, Johnny Cash arrived at San Quentin Prison, his voice nearly gone from a wild night in San Francisco. Haggard, then an inmate, was in the crowd of 5,000 men, each one hungry for something to break the monotony of prison life. “He just barely could talk,” Haggard remembered. “I thought this guy’s in trouble… he can’t talk, he can’t sing.” Country music wasn’t the cultural force it would later become, and Cash’s visit wasn’t met with universal excitement. But what unfolded on that stage would change Haggard—and the course of country music—forever.

Cash, ever the showman, asked for a glass of water before he began. He pointed to a guard standing in the doorway, chewing gum, and when the guard responded, Cash mimicked him. It was a small, rebellious act, but in a place where mocking a guard was unthinkable, it won over the entire audience. “He won the whole audience,” Haggard said. In that moment, Cash wasn’t just an entertainer—he was a symbol of defiance and hope.

After the show, guitars sprang up all over the prison yard. “There must have been 20 guitar players,” Haggard recalled. “All of a sudden we were more popular, we had more clout because we understood what that guy did.” Haggard, already known among inmates as a musician, became a mentor. Young prisoners approached him, asking how to play the intro to “Folsom Prison Blues.” The seeds of Haggard’s own musical career were being sown right there, behind bars.

But Haggard’s road to San Quentin had been long and troubled. A runaway by age 10, he stowed away on freight trains and cycled through juvenile detention centers, each stay followed by another escape. By 19, he’d landed in San Quentin, classified as a dangerous convict because of his history of running. For the first 18 months, he was locked down after 4 p.m., unable to participate in music or other activities. “With my reputation of escape, they wouldn’t let me out of the cell,” he explained.

Eventually, with help from fellow inmates who played on the prison’s “warden show,” Haggard’s classification was changed. He joined the show, earning two packs of Camels and a rare steak dinner—perks unheard of in the harsh world of San Quentin. Music became his lifeline, but prison life wasn’t just about survival; it was, in some ways, a strange adventure. Haggard found ways to make life inside more bearable: playing music, working in the laundry, sneaking onto the football field with his guitar, and even running a small business selling beer and cigarettes. “I had a loan company inside prison,” he admitted, half amused, half amazed at his own resourcefulness.

Still, reality caught up with him. At a parole hearing, an official remarked, “Looks like you’re having a real good time here.” Haggard hadn’t thought of it that way, but the comment was a wake-up call. He realized he couldn’t keep running from life—or from himself.

The root of Haggard’s troubles, he said, was the lack of separation between minor offenders and hardened criminals in the juvenile system. “It was kind of a crime school,” he said, explaining how he’d come to idolize notorious outlaws like Bonnie and Clyde and John Dillinger. “The possibility of having a career in music was way out of reason. I didn’t think that was possible, so I took the studying the bad way.”

Music, however, was always there, waiting. Inspired by Cash’s performance, Haggard began to see a new path. He poured his experiences into his songs, writing with a raw honesty that resonated with anyone who’d ever felt trapped or misunderstood. “Sing Me Back Home,” widely considered his greatest song, stands as a testament to this. “Even people that have never been to jail know somebody that’s been to jail, and they have an imagination of what it might be like,” he said. The song’s famous line—“the warden led a prisoner down the hallway to his doom, and I stood up to say goodbye like all the rest”—comes from a place of deep personal truth. Haggard’s music was never just about melody; it was about survival, redemption, and the faint hope of freedom.

As Haggard’s career took off, he watched the music industry change around him. The rise of digital platforms like iTunes and social media meant that artists no longer needed record companies to reach their fans. “There’s few people in the world that it has done as much for as it has me,” he said, noting that he could now cut deals directly with digital platforms and keep more of his earnings. His son managed his social media, but Haggard marveled at how technology had leveled the playing field for artists everywhere.

Reflecting on Johnny Cash, Haggard was quick to point out that Cash was no accident. “He was very, very intelligent,” Haggard said. “A lot of that stuff, it sounded like it might have just been something they stumbled onto, but they knew what they were doing.” Their friendship deepened over the years, and Haggard never lost his admiration for the man who, with a raspy voice and a rebellious heart, changed the lives of everyone who watched him play at San Quentin that day.

Haggard’s story is a reminder that redemption can come from the most unlikely places. For a young man who once saw music as an impossible dream, a single performance behind prison walls lit a spark that would burn for a lifetime. His songs, born from pain and perseverance, continue to resonate with listeners who see in Haggard’s journey a reflection of their own struggles and hopes.

In the end, Merle Haggard’s life is proof that even in the darkest places, music can lead the way out. And sometimes, all it takes is one man, one guitar, and the courage to tell the truth.

News

After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer walked into my office and smugly handed me divorce papers, saying, “She’ll be taking everything—the house, the cars, and full custody. Your kids don’t even want your last name anymore.” I didn’t react, just smiled and slid a sealed envelope across the desk and said, “Give this to your client.” By that evening, my phone was blowing up—her mother was screaming on the line, “How did you find out about that secret she’s been hiding for thirteen years?!”

Checkmate: The Architect of Vengeance After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer served me papers at work. “She gets…

We were at the restaurant when my sister announced, “Hailey, get another table. This one’s only for real family, not adopted girls.” Everyone at the table laughed. Then the waiter dropped a $3,270 bill in front of me—for their whole dinner. I just smiled, took a sip, and paid without a word. But then I heard someone say, “Hold on just a moment…”

Ariana was already talking about their upcoming vacation to Tuscany. Nobody asked if I wanted to come. They never did….

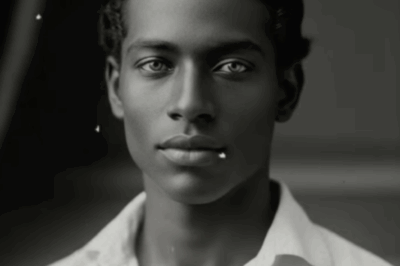

The Impossible Mystery Of The Most Beautiful Male Slave Ever Traded in Memphis – 1851

Memphis, Tennessee. December 1851. On a rain-soaked auction block near the Mississippi River, something happened that would haunt the city’s…

The Dalton Girls Were Found in 1963 — What They Admitted No One Believed

They found the Dalton girls on a Tuesday morning in late September 1963. The sun hadn’t yet burned away the…

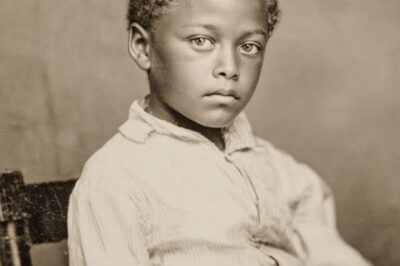

“Why Does the Master Look Like Me, Mother?” — The Slave Boy’s Question That Exposed Everything, 1850

In the blistering heat of Wilcox County, Alabama, 1850, the cotton fields stretched as far as the eye could see,…

As I raised the knife to cut the wedding cake, my sister hugged me tightly and whispered, “Do it. Now.”

On my wedding day, the past came knocking with a force I never expected. Olivia, my ex-wife, walked into the…

End of content

No more pages to load