If you ever wondered what happens when you put Morgan Freeman—the voice of God, the calm in every cinematic storm, and arguably the most universally respected man in Hollywood—on daytime television and try to box him into a political narrative, let’s just say: sparks fly, dignity is tested, and viewers get a masterclass in how to own your story without letting anyone else write it for you.

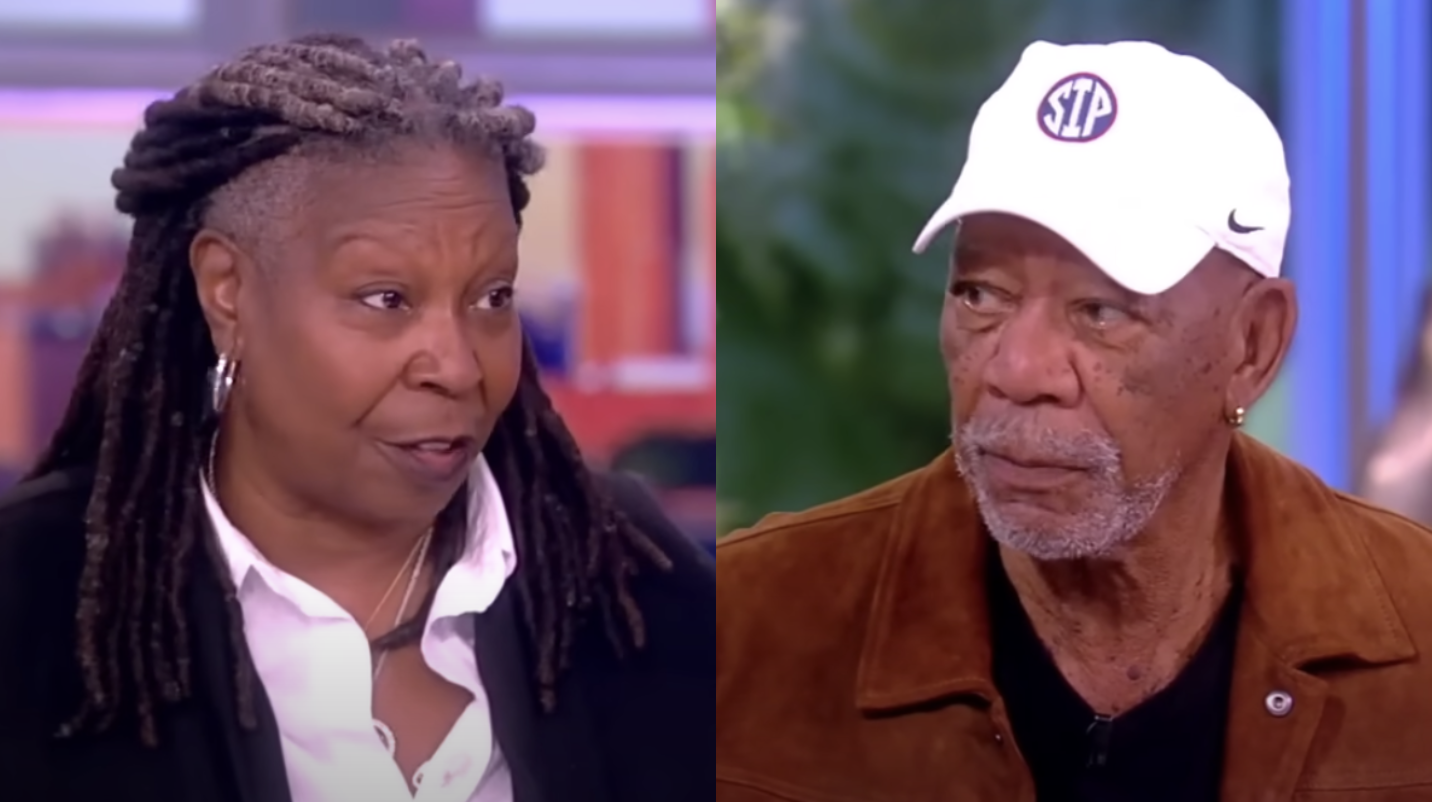

That’s exactly what unfolded on a recent episode of The View, where Freeman, invited to discuss his new documentary Life on Our Planet, found himself caught in the crosshairs of a panel more interested in steering the conversation into the choppy waters of climate doom and race politics than letting the man speak on his own terms. Five minutes. That’s all they gave him. Less time than it takes to microwave a frozen lasagna, and far less than any fan of Freeman would ever need to soak up his wisdom. It was a TV hit-and-run on a living legend’s dignity.

The segment started innocently enough. Freeman, with his signature velvet voice, began discussing the history of extinction-level events on Earth. “There have been, if I remember correctly, six extinction level events on the planet since life began. Large portions of life, not human life, just life—gone, destroyed. We’re headed for another one,” he warned, echoing the urgency scientists have expressed about climate change.

But the panel couldn’t resist. Rather than exploring the fascinating science and storytelling behind Freeman’s documentary, they veered into doomsday rhetoric, selling tickets to the end of the world with a side of guilt-tripping. The conversation quickly shifted from the resilience of life to the supposed villainy of humanity. Suddenly, it felt less like a celebration of Freeman’s work and more like an audition for the next Marvel supervillain—where humans play the role of mustache-twirling evil-doers, and the planet is the tragic hero.

Joy Behar, never one to shy away from a hot take, parroted lines straight from the far-left environmentalist playbook. “It’s tenacious if we would just leave it alone. And the human interruption of all that is what’s causing all the problems. I hope that it’s not too late.” You could practically see Freeman’s soul sigh. This wasn’t the detour he wanted. It was not the interpretation of his documentary he signed up for.

Here’s the thing: Freeman knows that over 99% of all species that have ever lived on Earth are already extinct. Dinosaurs, trilobites, giant sloths—gone. Life pops in and out like a cosmic game of whack-a-mole. But the planet itself? Tougher than a stale bagel. It has survived ice ages, meteors, and even the questionable fashion choices of the 1980s. And get this—there’s actually a fringe group online advocating for the voluntary extinction of the human race to save the planet. Freeman clearly wants no part of that extremism. He’s all for saving the earth, but he’d prefer to be around afterwards to enjoy it.

But the panel wasn’t finished. They pivoted to race relations, asking Freeman about another documentary he executive produced: 761st, about the first Black armored battalion to fight in World War II—the original Black Panthers. Again, instead of letting Freeman unpack the history and heroism of these soldiers, the panel tried to make him the reluctant mascot of a social message. Sunny Hostin, in particular, tried to frame the film as a political statement, but Freeman politely and firmly resisted. It was like inviting Gordon Ramsay to cook and then handing him a microwave burrito. You just don’t do that.

The tension was palpable. Freeman, with more gravitas in his pinky finger than the whole studio combined, gently corrected the panel. The five minutes they gave him felt less like an interview and more like speed dating with Morgan Freeman—except instead of romance, you got unsolicited political framing. The miscalculation was obvious. Freeman doesn’t need their narrative. He is the narrative.

As the conversation turned to Black representation in film, Freeman reflected on his own experience. “You start in the 40s and move up. And how many times did I see Black people in the movies? And if I did see them, what were they doing? They were servants. Always. It’s appalling.” He continued, “It shouldn’t be that way because somebody did make money. And there it was. That’s the time.” Freeman’s quiet confidence shone through. You can’t make someone feel like a victim if they’ve already decided they’re not going to play that role.

This is exactly what makes Morgan Freeman so compelling. He refuses to carry baggage that isn’t his. If you think this is overselling it, go back and watch his classic 60 Minutes interview. It’s a masterclass in how to shut down the victim narrative with nothing more than calm common sense and a voice that could convince you to refinance your mortgage. “How are we going to get rid of racism?” he asked. “Stop talking about it. I’m going to stop calling you a white man. And I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a Black man.”

The panel couldn’t muster a real disagreement. How could they? Freeman has lived it all. Born in 1937, now 84, he’s seen the arc of American culture bend and twist over decades. That kind of lived history isn’t something you can fact-check on Google. It’s carved into his perspective, which is why everything he says carries so much weight.

Art is a mirror of its culture, and culture is always shifting. What feels groundbreaking today might look outdated tomorrow, and that’s part of the beauty. To drag the past into the courtroom of modern morality is not only short-sighted, it’s disrespectful to the artists who paved the way. You don’t honor history by rewriting it with today’s hashtags. And you can bet good money Morgan Freeman doesn’t want that fate for himself either. When history remembers him—and it will—he’d want to be seen in the fullness of his time, not as some poor soul filtered through tomorrow’s outrage.

So, what’s the lesson here? If you invite Morgan Freeman onto your show, let him speak. Don’t try to box him into your narrative. Don’t hand him your political baggage and expect him to carry it. Freeman is not your spokesperson, therapist, or sociology professor. He’s Morgan Freeman—an artist, a storyteller, and a man who’s earned the right to define his own legacy.

Fans watching at home saw something rare: a celebrity who refused to be a symbol for someone else’s agenda. Freeman’s performance on The View was a gentle but firm reminder that dignity is best preserved when you refuse to play someone else’s role. And that’s why, even in five minutes, he made more of an impact than most guests do in an hour.

If you want to honor Morgan Freeman, listen to him. Let the man speak for himself. Because when he does, the world listens. And that’s something no panel, no hashtag, and no political framing can ever take away.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load