October 15th, 1945. A makeshift courtroom in Vspot, Germany, American occupation zone. Seven people stand before a military tribunal. They wear ordinary clothes, looking unremarkable and administrative. One is a head nurse, another managed hospital records, a third supervised meal preparation.

Today, American judges will convict them of murder—not for battlefield combat, not for following vague orders in chaos, but for paperwork, for signatures on transfer lists, for marking patients with red crosses, and watching buses arrive to take them away, knowing exactly where those buses were going and what would happen when they got there. Here’s what you need to understand before we go any further: these defendants had explanations and justifications. They argued they were following medical directives, claimed the patients were suffering anyway, insisted they didn’t know the full scope.

The American prosecutors listened to all of it. Then a single document, a transport list recovered from Hadamar psychiatric facility dated August 1942, destroyed every defense they offered. This wasn’t the largest mass killing site, nor the one that killed the most people, but it was the facility where American investigators found documentation so complete, so undeniably clear, that prosecuting mercy killing as systematic murder became unavoidable.

Today, I’m going to show you exactly what the transport list revealed—how the Action T4 program, the Nazi campaign to eliminate people with disabilities, was designed, how it was hidden in plain sight using medical bureaucracy, and how American military courts tore that bureaucracy apart page by page until the staff at Hadamar had nowhere left to hide. Because this isn’t just about one institution; this is about the moment American justice confronted medicalized killing and established a principle that still governs medical ethics today: that no diagnosis, no quality of life assessment, no cost-benefit analysis ever justifies taking a life without consent.

The phrase “life unworthy of life,” the administrative murder of institutionalized patients, the quiet elimination of people society deemed burdensome—every protection vulnerable people have in medical systems today exists because of what happened when American investigators walked into Hadamar in March 1945 and found filing cabinets full of death certificates, all bearing the same false cause of death written in the same handwriting on the same forms. So the question isn’t whether crimes happened at Hadamar—the evidence made that undeniable. The question is how American prosecutors proved that doctors and nurses who never held a weapon, who never shouted orders, who simply processed paperwork and administered medication, were guilty of premeditated murder.

Stay with me, because by the end of this, you’ll understand why three men who worked in a hospital became three names on a gallows list while their colleagues faced decades in prison for the same systematic killing. But first, we need to go back to March 1945, to the moment American soldiers entered Hadamar and discovered something that looked like a hospital but functioned like a death factory.

Before we dive in, if you’re interested in deep analysis of World War II atrocities, medical ethics violations, and how American military courts prosecuted crimes that didn’t fit traditional definitions of warfare, I’d really appreciate if you’d hit that subscribe button. It helps the channel grow and lets me know this type of content matters to you. And as we go through this story, drop a comment telling me where you think the line is between medical treatment decisions and murder. When does choosing not to treat become choosing to kill? I read every comment, and I’m genuinely curious what you think.

All right, let’s get into it. March 26th, 1945. American forces from the 65th Infantry Division enter the town of Hadamar, Germany, about 40 miles northwest of Frankfurt. It’s a small town, unremarkable, with a psychiatric hospital perched on a hill overlooking the valley. The hospital has been operating since the 1500s, a known facility, visible from the road, not hidden behind barbed wire or guard towers.

American military police enter the facility expecting to find what they found at other institutions: disorder, abandoned patients, staff who fled, records hastily destroyed. Instead, they find something different. Staff are still on duty, patient wards still operating, and an administrative office with filing cabinets organized by year, by patient name, by diagnosis. Ledgers track admissions and discharges; death certificates are filed chronologically. They find order—and that order immediately feels wrong.

Hadamar has a population of about five thousand people. But between 1941 and 1945, this small psychiatric hospital recorded more than 10,000 deaths. That’s not a hospital mortality rate; that’s an extermination rate. American investigators begin pulling files and discover a system so methodical, so bureaucratic, so carefully documented that it becomes impossible to claim anyone involved didn’t know exactly what was happening.

Let me explain what that system looked like. Understanding requires understanding Action T4, the program it was part of. Action T4 was the Nazi so-called euthanasia program, a systematic operation to kill institutionalized people with mental and physical disabilities. The program began in 1939, operated from an office at Tiergartenstrasse 4 in Berlin—hence the name T4—and it functioned like this.

Patients in psychiatric hospitals and care institutions across Germany were evaluated using standardized forms. The forms asked about diagnosis, work capacity, whether the patient had been institutionalized for more than five years, and whether they were considered criminally insane. These forms were sent to a central office in Berlin where panels of doctors reviewed them and marked certain patients for inclusion in the program.

The marking was simple: a plus sign meant transfer, a minus meant the patient could remain. Patients marked with a plus were told they were being transferred to specialized care facilities. Families received official letters explaining the transfer was for better treatment. What families weren’t told was that these transfers were one-way journeys to six killing centers across Germany, including Hadamar.

The system ran on paperwork—transfer orders, patient lists, authorization forms, transportation schedules, death certificates. Every step documented, every stage requiring signatures. And here’s what made it so insidious: it looked legitimate. It used real medical forms, real hospital stationery, real doctors’ signatures. The entire apparatus of institutional medicine was repurposed to make mass killing look like routine patient care.

Hadamar functioned as a T4 killing center from January 1941 until August 1941. During those eight months, approximately 10,000 people were killed in a gas chamber disguised as a shower room in the facility’s basement. The process was industrial: buses arrived daily—gray buses with covered windows. Patients were unloaded, taken to a reception area, stripped, led downstairs, and killed with carbon monoxide. Their bodies were cremated in ovens installed specifically for that purpose.

The entire process from arrival to cremation took about 24 hours. But here’s the part that American investigators found most chilling: the killing wasn’t hidden from the local population. The buses were visible on the roads, the crematorium smoke was visible from town. Children in Hadamar created a rhyme about the buses and hospital staff. Nurses, administrators, orderlies participated in every stage of the process while maintaining meticulous records of each death.

In August 1941, the gas chamber phase of T4 officially ended. Public rumors had spread, some families became suspicious, and a few clergy members began asking questions. The central program was suspended, at least officially. But Hadamar didn’t stop killing—it simply changed methods. From 1942 to 1945, Hadamar staff killed approximately 4,500 more people using a different approach: medication overdoses, starvation diets, and deliberate neglect.

No more gas chambers—just injections, reduced rations, and patients who wasted away while death certificates cited natural causes. And they documented all of it: admission forms, medical notes, death certificates, burial records. When American investigators found these records in March 1945, they faced a prosecutorial challenge: how do you prove murder when the victims were already institutionalized, when death certificates cite medical causes, when the killers can claim they were providing end-of-life care to suffering patients?

The answer came from the documents themselves. The records were so complete, so systematic, they revealed patterns that no legitimate medical facility would ever produce. Let me show you what I mean. American investigators found that Hadamar’s death certificates between 1942 and 1945 listed causes of death like tuberculosis, pneumonia, heart failure—all plausible for institutionalized patients.

But when investigators sorted the certificates chronologically and looked at the handwriting, they noticed something: dozens of certificates filled out on the same day, all listing different patients, all with different supposed causes of death, but all written in the same hand, all signed by the same doctor, all processed within hours of each other. That’s not how people die naturally. Even in an overcrowded wartime institution, deaths cluster around illness outbreaks or seasonal patterns. They don’t arrive in neat daily batches of five or six patients with varied diagnoses, all expiring on schedule.

The certificates themselves were evidence of systematic killing disguised as medical care. Then investigators found the transport lists—rosters of patients transferred to Hadamar from other institutions. The lists included names, dates of birth, diagnoses, dates of arrival. When investigators cross-referenced arrival dates with death certificate dates, a pattern emerged: patients from certain categories—those labeled work incapable, those diagnosed with schizophrenia or severe epilepsy, those transferred from other institutions—died within weeks of arrival, sometimes within days.

But here’s what changed everything, what gave American prosecutors the legal authority to bring charges. Among the dead weren’t just German citizens. Mixed into the transport lists were names that stood out: Polish names, Russian names, workers from occupied territories who had been sent to German factories, suffered mental or physical breakdowns from brutal conditions, and been transferred to Hadamar when they could no longer work.

These weren’t German nationals; these were foreign forced laborers. Under international law, even during wartime, their killing constituted a war crime. One transport list dated August 1942 became the centerpiece of the American prosecution. It documented 89 Polish and Soviet workers transferred to Hadamar from various labor camps and factories. Of those 89 workers, 76 were dead within three months. Their death certificates cited natural causes, but the statistical probability of 76 out of 89 previously healthy young workers dying of natural causes within 90 days was effectively zero.

That transport list, prosecution exhibit 12, became the document that collapsed the defendants’ explanations because it showed something undeniable: Hadamar wasn’t treating patients; it was receiving inconvenient foreign workers for elimination. And here’s the brilliant legal strategy the American prosecutors deployed: they didn’t try to prosecute the killing of German citizens by German staff. That would have raised complex questions about sovereignty, about whether Allied courts had jurisdiction over how Germany treated its own people.

Instead, they focused exclusively on the 476 Polish and Soviet forced laborers killed at Hadamar between 1942 and 1945. These victims were foreign nationals under the supposed protection of the Hague Convention. Their killing was clearly a war crime—no jurisdictional ambiguity, no sovereignty questions, just straightforward murder of protected persons during wartime.

But the documents revealed something even more damning. They showed intent. They showed that staff knew exactly what was happening and participated willingly—not under duress, not in fear of consequences, but as routine job duties. American investigators found personnel records showing that Hadamar staff received bonus payments for crematorium duty during the gas chamber phase and for working in what internal memos called “special wards” during the later injection phase.

These bonuses weren’t coerced compensation—they were incentive pay. Staff volunteered for these assignments because they paid more. Investigators found letters from staff to administrators requesting transfers to Hadamar specifically because of the extra pay and lighter workload. Lighter workload in an institution that supposedly provided intensive patient care—the contradiction was stark. Why would an institution dedicated to treating difficult cases offer easier work? The answer was obvious: the patients weren’t being treated—they were being killed, and dead patients require less care than living ones.

By April 1945, American military authorities had assembled enough evidence to proceed with prosecution. The decision was made to try staff in an American military court rather than wait for international tribunals. The reasoning was strategic: this would be a clear-cut case, well documented, limited in scope with defendants who couldn’t claim battlefield confusion or superior orders. It would establish American legal authority to prosecute Nazi crimes in occupied territory and set precedent for future trials.

The charges were filed under the Hague Convention and basic laws of war. The specific charge was violations of the laws and usages of war by killing Polish and Soviet nationals unlawfully confined at Hadamar. This narrow focus was deliberate. The United States didn’t claim jurisdiction over Germans killing German citizens—that would come later in German courts. This trial focused exclusively on war crimes committed against foreign nationals.

On October 8th, 1945, the trial began: United States of America versus Alons Klein et al. Hadamar, seven defendants. Klein, the chief administrator who signed transfer approvals; Armgard Huber, head nurse who oversaw medication distribution; Adolf Walman, the chief physician who certified deaths; Hinrich Ruff, a male nurse who administered fatal injections; Carl Villig, an administrator who processed paperwork; Philip Bloom, a gravedigger who buried victims; and Adolf Merkel, a driver who transported patients.

The trial was held in a converted theater in Vspotten. No international judges, just American military officers serving as a tribunal. The proceedings were swift and focused. The prosecution had a clear strategy: they would prove three things. First, that Hadamar systematically killed patients. Second, that the defendants participated in that system knowingly. Third, that among the victims were 476 Polish and Soviet forced laborers whose killing constituted war crimes under the Hague Convention.

The prosecution began by presenting the facility itself as evidence. Tribunal members visited Hadamar. They saw the basement room where the gas chamber had operated during the first phase. They saw the crematorium ovens still operational. They saw the special wards where the second phase killings took place—the rooms where injections were administered and patients were left to die from starvation rations. They saw the storage areas where patient belongings were sorted after death, clothing in one pile, valuables in another, everything cataloged for redistribution.

Then came the documents. Prosecutors entered hundreds of pages into evidence: transfer lists, death certificates, burial records, administrative memos, payroll documents showing bonus payments, supply requisitions for medications used in the killings. The paper trail was overwhelming. One document stood out—a memo dated March 1943 from administrator Klein to the facility’s purchasing department requesting additional supplies of luminal and morphine scopolamine.

The quantities requested were massive, far beyond what a psychiatric facility would need for legitimate therapeutic use. The memo included a notation for “special treatment” of incoming transports. That phrase appeared repeatedly in Hadamar documents—it was bureaucratic euphemism for killing.

The prosecution called witnesses. Former patients who survived testified about watching others receive injections and die within hours. They described staff members who selected patients for treatment with clinical detachment. They described how certain patients, particularly foreign workers, were segregated into specific wards and never seen again.

One witness, a Polish forced laborer institutionalized at Hadamar after a factory accident, described his experience in devastating detail. He testified that he arrived at Hadamar in July 1944 with a group of 12 other Polish and Russian workers, all transferred from other hospitals or directly from factories where they had suffered injuries or breakdowns. Within two months, 10 of those 12 workers were dead.

The witness survived only because a German nurse, apparently having a crisis of conscience, warned him to refuse medication and pretend to improve. His testimony was crucial because it established a pattern: the foreign workers weren’t dying from their original injuries or illnesses, they were being systematically eliminated shortly after arrival. And the staff—from administrators to nurses to orderlies—all participated in the process.

But here’s what made the prosecution’s case airtight: they didn’t just rely on testimony, they cross-referenced testimony with documents. When the Polish witness said 10 workers died within two months, prosecutors produced death certificates for all 10. When he described a specific nurse administering injections, prosecutors showed that nurse’s duty roster placing her in that ward on those exact dates. When he described bodies being removed at night, prosecutors produced burial records showing those patients interred on those nights.

The defense had an impossible task. The evidence was too systematic, too well documented, too consistent across multiple sources. But they tried several approaches, and watching those defenses collapse reveals exactly how American prosecutors dismantled the bureaucratic machinery of medicalized killing.

First, the defense argued medical necessity. Defense attorney Captain Leon Jaworski, who would later become famous as the Watergate special prosecutor, represented some of the defendants. He argued that Hadamar was overcrowded, resources were scarce during wartime, difficult triage decisions had to be made, and ending the suffering of patients who had no hope of recovery was a form of mercy.

The prosecution’s response was methodical. They called an American psychiatrist, a military doctor, who had reviewed Hadamar’s patient records. He testified that many of the patients killed at Hadamar had diagnoses that weren’t terminal: schizophrenia, epilepsy, depression, developmental disabilities. None of these conditions carry automatic death sentences. Many patients could have lived for years or decades with basic institutional care.

The psychiatrist went further. He reviewed the medical files of the Polish and Soviet workers who died—most had no psychiatric diagnoses at all. They had physical injuries, broken bones, concussions, trauma from factory accidents. They were sent to Hadamar not because they needed psychiatric care, but because they were foreign workers who had become unable to work. They were killed because they were no longer economically useful.

That testimony destroyed the mercy argument—mercy requires the patient’s interest to be paramount. Killing workers who became burdensome isn’t mercy; it’s elimination of inconvenient people.

Second, the defense tried to argue that deaths weren’t as systematic as prosecutors claimed. Defense attorneys pointed to Hadamar’s legitimate patient population—hundreds of German patients who received real care and survived. They argued that some deaths were inevitable in any institution, that wartime conditions made mortality rates higher, that isolated incidents of staff misconduct didn’t prove systematic murder.

The prosecution responded with statistics. They brought in a military intelligence officer who had analyzed mortality data. He presented a breakdown that was damning: between 1942 and 1945, German patients with certain diagnoses had a mortality rate of approximately 15%—high but explicable under wartime conditions. Polish and Soviet forced laborers had a mortality rate of 78%. That disparity couldn’t be explained by medical factors—it was explained by selection. Foreign workers were being systematically killed; German patients received actual care.

The officer went further. He showed that mortality spiked immediately after transport arrivals. When buses delivered new groups of workers, death certificates clustered in the following two weeks. Then mortality would drop until the next transport arrived. That pattern repeated monthly for three years. It was a killing schedule as regular and predictable as a factory production line.

Third, the defense tried the following orders argument. Several defendants claimed they were obeying directives from Berlin, that the T4 program was official government policy, that refusing to participate would have led to their own arrest, or worse, that they had no choice. This defense worked for some lower-level defendants initially, but the prosecution had evidence that undermined it completely.

They produced testimony from other staff members who had refused to participate in the killings and suffered no consequences. One nurse testified that in 1943 she requested a transfer out of the special ward because she was uncomfortable with what was happening there. Her request was granted; she was reassigned to a regular patient ward. No punishment, no retaliation, just a routine transfer.

That testimony proved that staff participation wasn’t coerced—it was voluntary. People who didn’t want to participate could avoid it. Those who did participate, especially those who sought out the assignments for bonus pay, made a choice.

For the senior defendants—Klein, Walman, Huber, Ruff, and Villig—the following orders defense failed even more completely because the evidence showed they weren’t just following orders; they were managing the system. Klein signed transfer approvals—he could have slowed the process, questioned orders, requested clarification. Instead, he processed transfers efficiently and collected bonuses.

Walman certified deaths—he could have insisted on accurate diagnosis, flagged suspicious patterns, reported concerns. Instead, he signed certificates with false causes of death, sometimes dozens in a single day.

Huber supervised medication distribution—she could have questioned dosages, refused to participate, sought transfer. Instead, she trained other nurses in the procedures and ensured the system ran smoothly.

These weren’t people trapped in impossible situations; these were people who made the system work.

And then came the moment that shifted the trial’s entire dynamic—the moment when the defense’s explanations didn’t just fail, they became morally repugnant. The moment when the tribunal’s faces changed from judicial neutrality to barely concealed disgust.

That moment came during the testimony of Margarete Borcowski, a German nurse who worked at Hadamar from 1942 to 1944 before requesting a transfer. Borcowski wasn’t a defendant; she had left Hadamar before the period covered by the charges. But prosecutors called her as a witness to describe how the system functioned from the inside.

Borcowski’s testimony was calm, factual, devastating. She described the routine during the second phase: transports would arrive in the morning, patients would be processed, examined, assigned to wards. Within a day or two, certain patients—always from specific categories, foreign workers especially—would be moved to a special section. That evening or the next day, those patients would receive injections. By morning, they’d be dead.

The prosecutor asked her to describe the injections. Borcowski explained that medications were prepared by senior nurses under Huber’s supervision. The injections were administered by nurses or orderlies, frequently by Ruff. The medications were overdoses of sedatives and morphine derivatives—doses far beyond therapeutic levels, doses that would cause respiratory failure within hours.

The prosecutor asked if patients consented. Borcowski’s answer was simple: no. Patients were told they were receiving medication to help them sleep or reduce anxiety. They weren’t told the injections would kill them.

The prosecutor asked if Borcowski ever questioned this. She said yes. She asked Huber why certain patients received such high doses. Huber’s response, according to Borcowski, was chilling in its bureaucratic plainness: “These patients are approved for special treatment. We’re following the protocol.”

Protocol. That word appeared again and again in the trial—killing reduced to protocol, murder transformed into administrative procedure. But then Borcowski testified to something that made the courtroom go silent.

She described an incident from August 1943. A transport of Polish workers arrived. Among them was a young man, perhaps 20 years old, who had suffered a head injury in a factory. He was conscious, coherent, confused about why he’d been sent to a psychiatric facility. Borcowski spoke enough Polish to communicate with him. He asked her when he’d be sent back to work. She didn’t answer.

Two days later, he was moved to the special ward. Borcowski saw Ruff prepare the injection, saw him administer it, saw the young man’s confusion turn to alarm as he realized something was wrong, watched him struggle weakly as the medication took effect, watched him lose consciousness within minutes. She described Ruff’s demeanor during this: calm, routine, mechanical, like a technician performing a standard procedure. No hesitation, no apparent moral conflict—just a task completed and documented.

The prosecutor asked Borcowski what happened next. She said the body was removed that night. A death certificate was issued the following morning listing cause of death as pneumonia. The young man had been at Hadamar for less than 72 hours. He’d shown no signs of respiratory illness. The certificate was signed by Dr. Walman.

The prosecutor entered that death certificate into evidence—Exhibit 47. A single sheet of paper with official stamps, neat handwriting, a doctor’s signature, and a complete lie. That moment broke the defense because Borcowski’s testimony, corroborated by a document with Walman’s own signature, showed that this wasn’t euthanasia, wasn’t mercy killing, wasn’t even medicalized eugenics driven by twisted ideology—it was murder for administrative convenience.

A young man who could have recovered, who wanted to live, who thought he was receiving medical care, was killed because he’d been categorized as no longer useful and sent to a facility that processed such people with bureaucratic efficiency.

Defense attorneys had no effective rebuttal. They tried to suggest Borcowski might be misremembering dates or details, but the death certificate was dated August 18th, 1943. Borcowski’s testimony placed the incident in August 1943. Transport logs showed a group of Polish workers arrived on August 16th, 1943. The evidence aligned perfectly.

The trial continued through October—more witnesses, more documents, more patterns of systematic killing exposed and documented. By October 14th, both sides had rested. The tribunal adjourned to deliberate. The deliberation took less than 24 hours. The evidence was overwhelming, the legal questions straightforward.

The defendants had participated in killing Polish and Soviet forced laborers who were non-combatants and therefore protected under international law. Intent was clear. Participation was documented. The only question was degree of culpability.

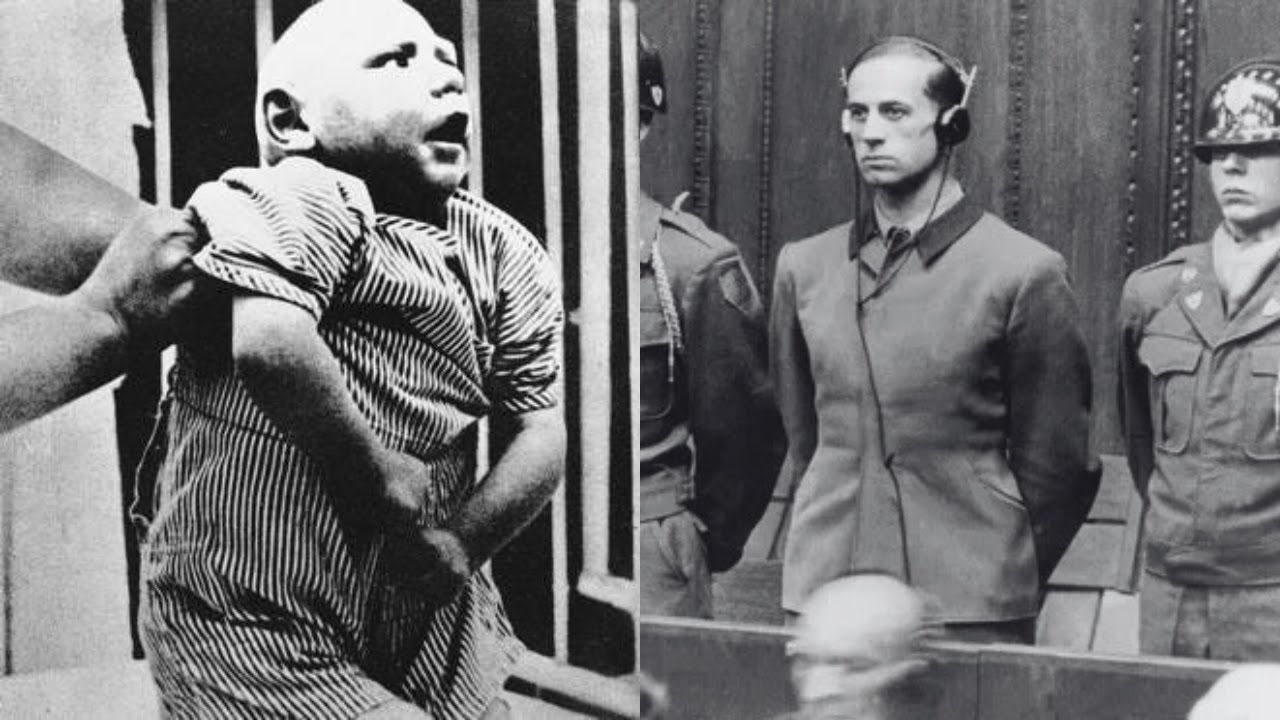

October 15th, 1945, the tribunal reconvened. The courtroom was packed with press, military observers, and German civilians curious about what American justice would look like. The verdict was read defendant by defendant.

Alons Klein—guilty. Chief administrator who signed transfer approvals and managed the facility’s killing operations. Evidence showed he signed documents authorizing admission of foreign workers, approved bonus pay for staff working in special wards, and personally supervised operations during both the gas chamber phase and the later injection phase.

Armgard Huber—guilty. Head nurse who supervised medication preparation and distribution. Evidence showed she trained other nurses in administering fatal injections, maintained logs of which patients received special treatment, personally oversaw the preparation of overdose medications that killed hundreds.

Adolf Walman—guilty. The chief physician who certified deaths and provided medical authority for the killing operations. Evidence showed he signed hundreds of false death certificates, approved patient selections for killing, and provided the medical legitimacy that allowed the program to function. At nearly 70 years old, Walman was the senior medical authority at Hadamar and bore ultimate responsibility for transforming medicine into murder.

Heinrich Ruff—guilty. Male nurse who administered injections. Evidence showed he was responsible for hundreds of deaths, received bonus payments for this work, and never expressed moral objection or attempted to refuse.

Carl Willig—guilty. Administrator who processed transfer paperwork and maintained patient records. Evidence showed he altered records to conceal patterns, fabricated discharge documentation for patients who had actually died, and helped create false paper trails that disguised systematic killing as routine patient care.

Philip Bloom—guilty. Gravedigger who buried victims. Evidence showed he processed hundreds of burials in short time frames, maintained logs that documented the systematic nature of the killings, and accepted payment for his work without reporting what was obviously mass murder.

Adolf Merkel—guilty. Driver who transported patients. Evidence showed he drove buses that collected patients from other institutions, transported them to Hadamar, and made these runs on regular schedules coordinated with killing operations.

The tribunal’s written judgment addressed the core legal questions directly. It established that the defendants had violated international law by killing Polish and Soviet nationals who were protected under the Hague Convention. It rejected the medical necessity defense by showing that victims weren’t terminal patients but economically unproductive workers selected for elimination. It rejected the following orders defense by demonstrating that participation was voluntary and that staff who refused assignment to killing duties faced no punishment.

But the judgment went further. It established a principle that would echo through subsequent war crimes trials. The tribunal stated that certain acts are inherently criminal regardless of domestic law or government policy, that national sovereignty doesn’t permit governments to murder vulnerable populations under medical pretenses, that medical personnel have obligations that transcend national loyalty or bureaucratic duty.

This was a precursor to concepts that would be formalized at Nuremberg—the idea that individuals are responsible for crimes against humanity even when acting under color of law, that following orders is not a defense to murder, that participation in systematic killing makes you a murderer regardless of your specific role.

Then came sentencing. The tribunal announced that three defendants would be executed by hanging: Alons Klein, Hinrich Ruff, and Carl Willig—the administrator who made the system function, the nurse who administered the fatal injections, and the clerk who created the false documentation. Three men whose combined actions made Hadamar’s killing machine operate smoothly would face capital punishment.

Armgard Huber, the nurse who supervised the preparation of fatal medications and trained others in the killing procedures, received 25 years in prison. Her role was essential to the system, but the tribunal distinguished between those who directly administered death and those who supervised and facilitated.

Adolf Walman, the chief physician who bore ultimate medical authority, received life imprisonment. At nearly 70 years old, his advanced age spared him from the gallows, but the tribunal made clear that his guilt was no less than those sentenced to death. As the senior doctor, he had transformed Hadamar from a hospital into a killing center. The tribunal noted that while age prevented execution, Walman would spend his remaining years in prison, denied the professional respect he had corrupted through systematic murder.

Bloom and Merkel received prison sentences of 25 and 30 years, respectively. Their roles were essential to the system but less directly connected to the killing itself.

The death sentences were controversial—some observers felt life imprisonment would be more appropriate, others argued that these were not high-level Nazi officials but mid-level functionaries who deserved punishment but not execution. But the tribunal’s reasoning was clear and deliberate: Klein, Ruff, and Willig had participated in systematic murder disguised as medical care. They had exploited their positions within a medical institution to kill vulnerable people. They had done so repeatedly, methodically over years.

Klein signed the approvals that brought victims to Hadamar. Ruff administered the injections that killed them. Willig created the false documentation that concealed their murders. Together, these three made the system work, and they had shown no remorse, no recognition of wrongdoing, only explanations and justifications.

The tribunal concluded that execution was necessary—not just as punishment, but as a statement. Medicine has boundaries that cannot be crossed. Administrative efficiency cannot excuse murder. And those who use bureaucratic systems to kill will be held accountable regardless of whether they pulled triggers or simply pushed papers.

March 14th, 1946. Brooksall prison, Germany. Alons Klein, Hinrich Ruff, and Carl Willig were executed by hanging. The executions were carried out by American military personnel. The process was documented but not publicized. There was no media circus, no spectacle—just three people who had killed hundreds paying with their own lives.

Their executions marked a turning point in how the world understood medical killing. The Hadamar trial was one of the first to establish that euthanasia without consent is murder, that medical professionals cannot hide behind diagnoses or quality of life assessments to justify killing patients, that institutional medicine requires external oversight precisely because medical authority creates opportunities for abuse.

These principles shaped everything that came after—the Nuremberg medical trial, which began in December 1946, built directly on precedents established at Hadamar. The tribunal’s reasoning about medical ethics, informed consent, and the limits of medical authority traced back to the arguments American prosecutors made in that converted theater in Vspotten.

The broader T4 program was prosecuted in subsequent German courts. Approximately 30 additional doctors, nurses, and administrators were tried between 1946 and 1948. Some received death sentences, others received long prison terms. Many of the T4 program’s architects had committed suicide in 1945 or fled beyond Allied reach.

But the Hadamar trial established something that transcended individual prosecutions. It established legal recognition that disability doesn’t diminish human worth, that quality-of-life judgments cannot justify ending life without consent, that society has an obligation to protect its most vulnerable members from medical systems that might view them as burdensome.

Let me show you why this matters today—why a trial that lasted seven days in October 1945 still shapes medical ethics 80 years later. When modern health care systems implement safeguards for vulnerable patients, those safeguards exist because of Hadamar. When medical ethics boards review end-of-life care protocols, they’re applying principles that emerged from prosecuting T4. When disability rights advocates argue against quality-of-life assessments being used to determine medical treatment, they’re standing on legal ground established in Vspotten.

The principle is fundamental and non-negotiable: no medical professional, regardless of their expertise or good intentions, has the authority to determine that another person’s life is not worth living. That decision belongs exclusively to the person whose life it is. If that person cannot make the decision due to incapacity, then the decision defaults to preserving life, not ending it based on others’ assessments of its value.

That principle seems obvious now. In 1945, it wasn’t universally accepted. Eugenics programs existed in multiple countries. Forced sterilization was legal in many jurisdictions. The idea that society could make reproductive or life-death decisions for people with disabilities had mainstream support in medical and policy circles.

The Hadamar trial helped destroy that consensus by documenting exactly what medicalized killing looked like in practice—by showing how bureaucracy made murder routine, by demonstrating that medical professionals could become serial killers while maintaining professional detachment. The trial made it impossible to maintain the fiction that eugenic elimination could be humane or ethically justified.

But here’s something that complicates the legacy, something most people don’t know. After the trial, questions emerged about what to do with the data. T4 programs had generated medical records on thousands of patients. Those records contained information about disabilities, institutional care outcomes, survival rates under various conditions.

Some researchers quietly argued that the data, however unethically obtained, might have scientific value. That argument was rejected decisively and completely. Medical organizations declared that data obtained through murder was scientifically worthless and morally contaminated. Using it would legitimize the methods used to obtain it.

The principle established was absolute: no data obtained through non-consensual harm to subjects can ever be used regardless of potential benefits. That principle now governs all medical research. It’s why institutional review boards exist. It’s why informed consent isn’t optional. It’s why research that violates ethical standards is unpublishable regardless of its findings. The line drawn at Hadamar holds.

But there’s another legacy, darker and more troubling. The trial exposed how easily ordinary people participated in systematic killing when it was framed as administrative duty. Klein wasn’t a sadistic monster; he was a bureaucrat who signed forms. Huber wasn’t a cruel torturer; she was a nurse who followed protocols. Ruff wasn’t a violent criminal; he was a medical worker who gave injections. Willig was a clerk who maintained files.

None of them fit the stereotype of a murderer. All of them killed hundreds of people. And they did it by treating murder as routine work—by fragmenting the killing process so that no single person felt fully responsible, by using medical and administrative language to obscure what was actually happening.

That insight—that ordinary people in ordinary roles can commit extraordinary evil when the system makes it routine—shaped Hannah Arendt’s later concept of the banality of evil. It influenced Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments. It became central to understanding how genocide happens—not through widespread sadism, but through widespread compliance.

The Hadamar trial was one of the first times this dynamic was documented in a legal proceeding. Prosecutors showed exactly how bureaucratic systems enable atrocity, how signatures on forms become tools of murder, how professional detachment becomes moral blindness, how just following protocol becomes just following orders becomes participation in systematic killing.

And here’s what makes this particularly relevant today. Modern institutions—medical, governmental, corporate—still operate through bureaucratic systems, still fragment responsibility across multiple roles, still use technical language that obscures moral dimensions of decisions. The mechanisms that made Hadamar possible haven’t disappeared—they’ve just been constrained by legal and ethical frameworks established partly through trials like this one.

Those frameworks aren’t automatic; they require constant reinforcement. Medical ethics boards aren’t self-enforcing. Disability rights protections require vigilant advocacy. The principle that vulnerable people deserve protection from institutional systems that might view them as burdensome has to be actively maintained because the alternative was documented in those filing cabinets American investigators found in March 1945.

Transport lists showing 476 Polish and Soviet workers sent to Hadamar. Death certificates with false causes, burial records, the administrative machinery of murder preserved in triplicate, filed by date. Everything in order. The Hadamar trial forced the world to confront what that order concealed—forced society to recognize that medicine without ethics is simply violence with medical training, forced legal systems to establish that institutional killing, regardless of how it’s justified or documented, is murder.

So, let me leave you with two questions, and I genuinely want to hear your thoughts in the comments. First, do you think the death sentences for Klein, Ruff, and Willig were justified? They were mid-level functionaries, not the architects of T4. They participated in a system created by others. Does that diminish their culpability, or does willing participation in systematic murder deserve the ultimate penalty regardless of who designed the system? And what about Walman, the senior doctor who escaped execution only because of his age?

Second, where’s the line between legitimate medical decision-making and the kind of quality-of-life assessments that enabled T4? Modern medicine makes triage decisions, allocates scarce resources, sometimes chooses not to provide certain treatments based on likely outcomes. How do we ensure those decisions never slide back toward the logic that justified Hadamar? What safeguards matter most?

Drop your thoughts below. I read every comment, and these questions don’t have easy answers, but they’re worth wrestling with because the principles established in that courtroom in Vspotten in October 1945 still protect all of us today.

If you found this analysis valuable—if you learned something about how American military courts confronted medicalized killing and established principles that still govern medical ethics—please hit that like button and subscribe. This type of deep historical dive takes serious research, and I can only keep making these videos if they reach people who care about understanding how the past shapes the protections we have today.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load