Don Knotts’ name instantly conjures up memories of nervous stammers, bug-eyed glances, and a laugh that echoed through living rooms for generations. As Barney Fife, the bumbling deputy on The Andy Griffith Show, Knotts won five Emmys and became one of television’s most beloved icons. But behind the applause and comedic brilliance, there was a story few ever saw—a story of fear, illness, and loneliness. Now, at 71, his daughter Karen Knotts is breaking her silence, sharing the private pain her father carried behind decades of smiles. Her revelations aren’t meant to tarnish his memory, but rather to complete it, painting a fuller portrait of the fragile soul behind the lovable deputy.

Jesse Donald Knotts was born on July 21, 1924, in Morgantown, West Virginia, the youngest of four brothers in a family already struggling to make ends meet. His mother, Elsie Lucetta, was 40 when he was born, and his father, William Jesse, battled personal demons that made home life unpredictable. Stability was elusive, and young Don grew up in a world of uncertainty. His older brothers were distant, living in their own worlds, but Don found joy in his brother Sid, whose sense of humor could brighten even the darkest days. Sid’s sudden death from an asthma attack devastated Don, marking his first real encounter with loss and leaving a shadow that never truly faded.

Amid hardship, Don turned to his imagination for refuge. He created a dummy named Danny, who became both a friend and a comedic partner. With Danny, Don invented playful routines that helped him forget the troubles surrounding him. At school, he began to use humor more openly, performing sketches that revealed a spark of talent. Though classmates elected him class president and enjoyed his company, Don still felt like an outsider, forever aware of the gap between how others saw him and how he felt inside. Karen Knotts later reflected that her father’s nervous, high-strung persona on screen was not merely an act—it was a reflection of the anxiety he carried from childhood. Every laugh, every exaggerated twitch came from something real. Comedy became his armor, transforming fear into connection.

Don’s first attempt at show business in New York ended in disappointment, sending him home crushed but not defeated. In 1943, with World War II raging, he enlisted in the Army—not for combat, but to serve in the 6817th Special Services Battalion, entertaining soldiers under constant strain. Touring across the Pacific with the variety show Stars and Gripes, Don discovered the power of his nervous energy. Soldiers loved him, not because he was heroic, but because he mirrored their own vulnerability, turning pain into laughter. When he left the Army in 1946, he was decorated with medals including the World War II Victory Medal and the Philippine Liberation Medal. But beyond the honors, he carried a sharpened stage presence and a sense of purpose he’d never felt at home.

After the war, Don returned to West Virginia University, earning a degree in education with a minor in speech in 1948. On campus, he performed often, using both his dummy Danny and his quick wit to win over audiences. He also met and married Catherine Metz, a minister’s daughter, in 1949. With just $100 in his pocket and Catherine by his side, Don returned to New York City, this time armed with experience and resilience. Success didn’t come overnight. Casting directors found him too awkward for leading roles, but his persistence paid off with radio gigs and small performances. Slowly, a career began to take shape. He landed roles on radio westerns like Bobby Benson and the B-Bar Riders, and eventually appeared on television in Search for Tomorrow. For the first time, his anxious mannerisms found a home on screen.

By the mid-1950s, Don Knotts was no longer just another struggling actor. His unique style caught the attention of Steve Allen, who cast him in comedic sketches on The Steve Allen Show in 1956. Don played jittery, bug-eyed characters in mock interviews, and audiences loved it. For the first time, his nervous energy wasn’t a liability—it was his signature. That same year, he reconnected with Andy Griffith on Broadway in No Time for Sergeants. Don’s portrayal of a bumbling corporal was a perfect match for Andy’s country charm, and their chemistry was undeniable. It planted the seed for what would become one of television’s most iconic partnerships.

In 1960, Andy Griffith launched The Andy Griffith Show. Don, half-joking, suggested he be cast as the deputy to Andy’s sheriff. The idea stuck, and soon Barney Fife was born. It was the role that changed everything. Week after week, Don transformed awkwardness into pure comedy gold. His twitchy expressions, stammering delivery, and boundless energy turned Barney into a national treasure. Within five years, Don had earned five Emmy Awards and cemented his place in television history.

But success on screen came at a heavy cost behind the scenes. His marriage to Catherine Metz, which had begun with so much promise, was collapsing under the weight of his career. The long hours on set and Don’s relentless anxiety created a distance that neither could bridge. Reports suggest that Catherine never fully connected with the Hollywood circle, and her relationship with Andy Griffith’s wife was strained. After thirteen years and two children, the marriage ended in divorce. Karen Knotts later admitted that while audiences adored her father, life at home was far from easy. Don’s constant worry, exhaustion from performing, and dependence on anxiety medication made family life turbulent. The man who made millions laugh often returned home drained and silent. For Karen, the contrast between America’s favorite deputy and the father she knew was stark. The breakthrough that gave Don fame also deepened the personal struggles that haunted him for decades.

At the height of his fame in 1965, Don made a decision that shocked fans. Believing The Andy Griffith Show would end after five seasons, he declined to renew his contract and signed a movie deal with Universal Pictures. He dreamed of becoming a leading man, of stepping out from Barney Fife’s shadow. For a time, it seemed possible. Films like The Incredible Mr. Limpet and The Reluctant Astronaut allowed him to headline, but the magic of Mayberry was hard to replicate. Audiences loved Don, but only as the jittery sidekick. His 1969 film, The Love God?, a risqué comedy about a Playboy publisher, proved that viewers couldn’t accept him as a romantic lead. The box office stumbled, and so did Don’s confidence.

Meanwhile, his private battles intensified. Don had long suffered from crippling anxiety, often spending days in bed before a performance. Doctors prescribed medication in the 1950s, but it quickly became a crutch. Karen would later reveal that the anxious characters audiences laughed at were a mirror of her father’s own fears. He wasn’t just acting nervous—he was living it. As his film career struggled, the gap between the man and the mask widened. By the 1970s, Don attempted to reinvent himself with The Don Knotts Show, a variety program meant to showcase his talents. But the series failed to compete with other popular variety shows and was cancelled within a year. Professionally, he continued to find work—guest appearances, Disney comedies, and later recurring roles on Three’s Company. Yet, despite steady jobs, there was a lingering sense of decline. He was no longer the Emmy-winning star, but a supporting act, filling spaces once lit by brighter flames.

Personally, Don drifted. His first marriage was over, and though he was often seen with women, lasting companionship eluded him. Karen recalled that people loved Barney Fife, but they didn’t always know how to love Don Knotts. Fame gave him recognition, but it did not cure the isolation or the gnawing sense that his best days had already passed.

By the 1980s, Don Knotts had secured his place as a television legend, but his personal life was unraveling once again. His second marriage to Laura Lee Szuchna ended in 1983 after nearly a decade of tension. The breaking point came when Don was diagnosed with macular degeneration, a disease that threatened to rob him of his eyesight. The news devastated him. For a man whose livelihood depended on timing, expressions, and performance, the possibility of blindness was unbearable. Laura Lee later admitted that his despair over the diagnosis, and the way it consumed him, was what finally ended their marriage. Thankfully, surgery restored much of his vision, but the scare left deep emotional scars.

Don’s reliance on smoking throughout his life had already done its damage. By the late 1990s, he was facing lung cancer. Though he had quit smoking more than a decade earlier, the disease returned to collect its debt. Even then, Don kept the seriousness of his illness quiet, not wanting to shatter the image fans held of him. He still cracked jokes and brushed off questions, insisting he would recover.

Amid this turmoil, Don found unexpected love once more. In 1987, while working on the sitcom What a Country, he met actress Frances Yarborough. At the time, she was much younger and worked behind the scenes helping Don with lines. Their connection seemed unlikely, but over time, it deepened into something real. In 2002, they married, giving Don the stability he had long craved but rarely found. Frances later said she was drawn to his vulnerability, the way he could make the world laugh while privately fighting so much pain. Their years together were brief. By 2006, Don’s cancer had progressed beyond treatment. Even as his health failed, he refused to give in to despair. He kept up his humor, performing one last private show for family and friends who visited him at his bedside. Karen recalled that even as he lay dying, he made them laugh so hard she had to leave the room. It was his final gift—the instinct to create laughter in the face of death.

In February 2006, Don Knotts’ condition worsened. The cancer spread and doctors at UCLA Medical Center knew his time was short. Family and close friends gathered quietly around his bedside. Among them was Andy Griffith, the man who had once been his partner in television magic. Griffith later recalled those final moments in an interview with Larry King. He whispered to Don, calling him “Jess,” a name known only to the closest of friends, and begged him to keep breathing. Though Don could no longer speak, he moved his shoulder slightly—a final acknowledgement that he had heard, that their bond remained unbroken even at the edge of death. It was a private farewell between two men whose friendship had defined an era of television.

Karen was also there, holding her father’s hand. She later admitted that his instinct for comedy never left him. Even as he struggled to breathe, he said or did something so funny that Karen and her stepmother burst into laughter. Karen ran out of the room, ashamed to laugh in front of her dying father. Years later, she regretted it deeply. A director friend reminded her that laughter was what Don lived for, and that he would have wanted her to stay. “I should have just stood there and laughed,” she later confessed. That was who he was.

At 81 years old, Don Knotts passed away on February 24, 2006. The man who brought so much joy left quietly, with his family at his side. His final wife, Frances Yarborough, inherited his estate, but the legacy Don left was not measured in property. It was in the laughter echoing across generations.

In her memoir, Tied Up in Knotts, Karen finally revealed the full truth about her father’s life—the painful childhood, the lifelong battle with anxiety, the loneliness fame could never heal. She did not write to expose him, but to honor him, to show that behind the lovable Barney Fife was a man of immense complexity. Her words remind us that the ones who make us laugh the hardest are often the ones carrying the heaviest burdens. Don Knotts lived a life full of contradictions. To the world, he was the beloved deputy who stumbled his way into television history. To his family, he was a man battling demons of anxiety, loneliness, and fragile health.

Karen Knotts, now 71, has broken her silence not to tarnish his image, but to give us the whole truth—a reminder that even the brightest laughter often comes from the darkest places. What remains is his legacy of joy, unforgettable characters, and courage in the face of private pain. Don Knotts never stopped making people laugh, even in his final hours. That, perhaps, is the truest measure of his gift.

News

After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer walked into my office and smugly handed me divorce papers, saying, “She’ll be taking everything—the house, the cars, and full custody. Your kids don’t even want your last name anymore.” I didn’t react, just smiled and slid a sealed envelope across the desk and said, “Give this to your client.” By that evening, my phone was blowing up—her mother was screaming on the line, “How did you find out about that secret she’s been hiding for thirteen years?!”

Checkmate: The Architect of Vengeance After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer served me papers at work. “She gets…

We were at the restaurant when my sister announced, “Hailey, get another table. This one’s only for real family, not adopted girls.” Everyone at the table laughed. Then the waiter dropped a $3,270 bill in front of me—for their whole dinner. I just smiled, took a sip, and paid without a word. But then I heard someone say, “Hold on just a moment…”

Ariana was already talking about their upcoming vacation to Tuscany. Nobody asked if I wanted to come. They never did….

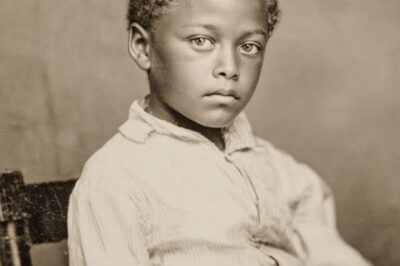

The Impossible Mystery Of The Most Beautiful Male Slave Ever Traded in Memphis – 1851

Memphis, Tennessee. December 1851. On a rain-soaked auction block near the Mississippi River, something happened that would haunt the city’s…

The Dalton Girls Were Found in 1963 — What They Admitted No One Believed

They found the Dalton girls on a Tuesday morning in late September 1963. The sun hadn’t yet burned away the…

“Why Does the Master Look Like Me, Mother?” — The Slave Boy’s Question That Exposed Everything, 1850

In the blistering heat of Wilcox County, Alabama, 1850, the cotton fields stretched as far as the eye could see,…

As I raised the knife to cut the wedding cake, my sister hugged me tightly and whispered, “Do it. Now.”

On my wedding day, the past came knocking with a force I never expected. Olivia, my ex-wife, walked into the…

End of content

No more pages to load