Twelve families. Twelve names that once ruled Robertson County, Tennessee, with the quiet arrogance of men who believed their power was eternal. For decades, their influence reached into every courtroom, every bank, every field and ledger. But between 1847 and 1860, those names disappeared—changed, scattered, buried in the dust of four states. What could drive the county’s richest, most respected families to abandon everything they’d built? It wasn’t war. It wasn’t plague. It wasn’t money. It was a woman named Eliza Harwell, and the truth she carried in her memory.

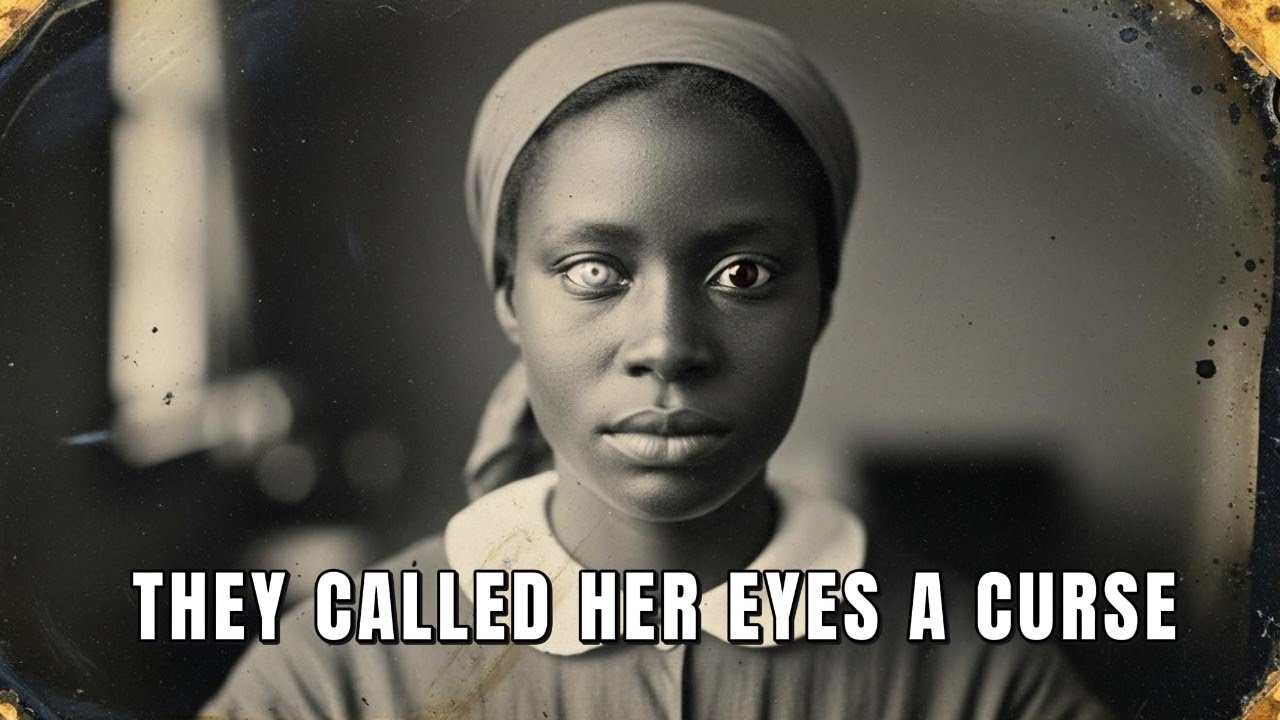

Eliza was born in the spring of 1824, in a cabin behind the imposing brick house of Colonel James Harwell’s plantation. The midwife, Ruth, had delivered hundreds of children—free and enslaved—but she’d never seen a baby with eyes like Eliza’s. One was pale blue, the color of a winter sky. The other, deep brown, almost black. Heterochromia, though no one in Robertson County knew the word. They called them “witch eyes.” Old superstitions whispered that such a child could see things others couldn’t. Ruth wrapped Eliza in cloth, her hands trembling. Sarah, Eliza’s mother, saw the fear and made a decision: her daughter would be raised quietly, taught to blend in, to survive.

But Eliza was never ordinary. By age four, she could recite songs after hearing them once. By six, she remembered conversations from years before, down to the weather and the clothes people wore. Her memory was perfect—uncanny. Martha, the head housekeeper, noticed first. She warned Sarah: “Teach her to forget, or pretend to. Make her seem ordinary.” Intelligence in the quarters was dangerous. But some things couldn’t be hidden.

In August 1830, Colonel Harwell hosted a dinner for eleven men—judges, bankers, merchants, and landowners. Eliza, only six, refilled glasses and cleared plates, ignored as children often are. She listened as they spoke freely, believing no one important was present. Judge Thornton laughed about dismissing a freedman’s case to reclaim his children. Edward Vance boasted of buying land from a widow who never knew her husband had signed it away. Colonel Harwell described a plan to seize farmland along the Cumberland River, using manipulated debts and coordinated foreclosures.

Then the conversation turned to Grace Thornhill, a free woman of color who owned forty acres outside Springfield. She’d inherited it from her white father, followed every law, paid every tax. But the men spoke of “appropriate pressure”—legal challenges, manufactured debts, and technicalities that would force her off the land. “She’ll sell, or circumstances will create opportunities for acquisition,” Harwell said. Two months later, Grace’s farmhouse burned to the ground. She died in the fire. Her land was auctioned and bought by Edward Vance for half its value.

Eliza remembered every word. She remembered the casual cruelty, the laughter, the confidence. She remembered the names, the dates, the plans. At six years old, she became an archive of corruption.

Years passed. Eliza grew, working in the Harwell house, her memory sharpening with every overheard conversation. Martha died in 1833, warning Eliza: “Gifts can be curses. Learn what to say, and what to keep silent.” Eliza learned to hide her intelligence, but her mismatched eyes made her impossible to ignore. By the mid-1830s, Colonel Harwell began using her as a living record. He’d ask her to recount what Judge Thornton had said about a land case, and she’d repeat every word. Guests marveled, speculated about her eyes and memory, never realizing what she truly understood.

She cataloged secrets: which debts were fabricated, which court cases decided before they were heard, which marriages arranged for money. She mapped the connections between the twelve men who met at the Harwell plantation—the Springfield Association. No official record existed. No charter, no membership list. But their coordination was absolute. They controlled land, courts, banks, and futures.

Colonel Harwell’s health failed in 1841. His son, James Jr., returned from Nashville, eager to inherit not just the plantation, but his father’s place among the twelve. James Jr. was ambitious, reckless, and desperate to prove himself. He hosted more meetings, discussed Eliza’s abilities openly, and made a crucial mistake: he underestimated her.

In February 1843, James Jr. told Edward Vance and Marcus Pedford that Eliza could be “leased” to other members for recordkeeping. Pedford warned, “She already understands. The question is what she plans to do with that knowledge.” James Jr. laughed. “She’s property. Who would believe her?” But Pedford had revealed a weakness: the Association feared written evidence. For twenty years, they’d kept their most damaging secrets off the books, trusting that no one could remember it all. They were wrong.

As Colonel Harwell died and James Jr. took over, Eliza’s access grew. She heard Batson describe rigged scales and cheated farmers. Cunningham boast about loans designed to guarantee foreclosure. Yatesman explain how rumors destroyed political rivals. She heard the will contested by Catherine Morrison, Harwell’s daughter, and learned how the Association coordinated witnesses and rulings to ensure James Jr. inherited everything.

Eliza understood the web. Each man’s secrets were entangled with the others. Expose one, and the whole structure collapsed. She was powerless by law, but her memory was a weapon. The question was how to use it—and whether she could survive the cost.

In 1844, James Jr. made a disastrous investment in cotton futures, losing $8,000 and dragging three other members down with him. The Association’s unity fractured. Tensions rose. James Jr., desperate for money and to eliminate a liability, decided to sell Eliza—south to Mississippi or Louisiana, where her memory would be lost forever.

Eliza learned of the sale eight months in advance. She began planning. First, she taught herself to write, practicing with charcoal on boards, letters in dirt, words in ash. By March 1845, she could compose a simple letter. Second, she needed an ally—someone outside Robertson County’s power structure.

In May, Reverend Thomas Walsh arrived for revival services. Known for sermons against corruption, he stayed three nights at the Harwell plantation. Eliza left a letter on his pillow, unsigned: “If you wish to learn of great corruption, walk past the east oak tree at dawn Thursday. Come alone.” Walsh found the letter, and at dawn, Eliza met him. She recited his Tuesday sermon word for word—thirty-seven minutes, every example, every scripture, every phrase. Walsh was shaken. “That’s not a normal gift,” he said. “No, sir,” Eliza replied. “But what I’ve witnessed isn’t normal either. It’s evil disguised as law.”

She explained: she was to be sold in eight weeks. If she disappeared, so did everything she knew. But if Walsh could help her secure freedom, she would testify—give dates, names, amounts, details. Walsh prayed, considered, and five days later, Eliza received word: help was coming.

On July 5, 1845, two days before her scheduled sale, a Nashville attorney offered James Jr. $1,300 for Eliza’s freedom, processed through Davidson County courts. James Jr. took the money, thinking only of his debts. Eliza became a free woman on July 12, 1845, protected in Nashville.

The realization hit the Association like a storm. James Jr. called an emergency meeting. They’d lost control of their living archive. Twenty years of secrets were now in the hands of someone legally free, protected, and ready to speak. Panic spread. Some suggested buying her silence; others, more extreme measures. But violence against a free woman in Nashville would bring ruin. They were trapped by the very system they’d built.

Eliza’s testimony began in September 1845, in a property restoration case for Grace Thornhill’s heirs. She recounted the 1830 meeting—who spoke, what was said, how the plan was coordinated. Defense attorneys objected, but the court allowed her to demonstrate her memory. She recited opening statements from two days earlier, word for word. Records matched her testimony. Where records were missing, the pattern of loss supported her claims of manipulation.

The verdict: Thornhill’s land was restored, with damages. More cases followed. Eliza testified in eleven proceedings, detailing schemes, fraudulent deeds, and coordinated foreclosures. Edward Vance’s empire collapsed. He fled to Texas, dying bankrupt and disgraced. Cunningham resigned from the bank, facing civil penalties. Batson’s gin operation was sued by dozens of farmers, his business ruined. Greer was removed from the land office, facing criminal charges. One by one, the twelve families fell.

The legal climax came in May 1847, in a consolidated criminal trial in Nashville. Eliza testified for six days, dismantling two decades of corruption. Defense attorneys attacked her memory, her motives, her mental stability. Doctors testified her mind was sound. The specificity of her testimony—details from years before anyone knew she’d ever testify—was impossible to dismiss.

Verdicts were mixed. Judge Thornton was convicted of misconduct and removed. Pedford was disbarred. Others paid fines or served brief jail terms. The system protected its own, but the Association was destroyed. Properties sold, careers ended, reputations shattered. The twelve families scattered, some changing names, others leaving Tennessee.

Eliza lived quietly in Nashville for the next twenty-six years. She married David Porter, a freedman, and raised three children. Census records list her as a laundress, but court documents suggest her memory continued to serve, testifying in cases where her eyes—one blue, one brown—were always mentioned. She never returned to Robertson County. The $50 she received from the anti-slavery society, and payments from families whose property she helped restore, allowed her a modest life.

The old families faded. Some changed names—Kilibru became Kilborne, Yatesman’s children moved to Alabama, Whitley’s son to St. Louis. Others simply vanished. The Harwell plantation was foreclosed and sold. The courthouse fire of 1891 destroyed many records from the 1840s. Some call it accident; others suspect descendants trying to erase history.

What remains are fragments—newspaper accounts, court documents, family stories. Some claim Eliza was manipulated, her memory unreliable. But the pattern is clear: twelve families collapsed after her testimony, in courts biased against her. The evidence suggests the corruption was real, the destruction earned.

Eliza left no memoir. She died in Nashville in 1873, buried in an unmarked grave. No monument marks her resting place. The plantation is gone, subdivided and built over. But in the hidden corners of Middle Tennessee history, her story persists. A woman with unmatched eyes, who saw everything and forgot nothing. A curse that was nothing more than the consequences of powerful men who believed they could speak freely in front of someone they thought less than human.

In the end, Eliza needed no supernatural power. She needed memory, patience, courage, and the chance to speak. She told the truth with such precision that it couldn’t be denied. That was all it took to bring down an empire built on lies and arrogance.

The past is never as buried as the powerful might wish. Sometimes, justice arrives not through armies or laws, but through a single voice, finally given the chance to speak. And sometimes, memory is more powerful than any curse.

What do you think? Is the story complete, or are there secrets still buried in Robertson County, waiting to be uncovered? The truth, as always, is stranger and more terrible than fiction.

News

At my son’s wedding, he shouted, ‘Get out, mom! My fiancée doesn’t want you here.’ I walked away in silence, holding back the storm. The next morning, he called, ‘Mom, I need the ranch keys.’ I took a deep breath… and told him four words he’ll never forget.

The church was filled with soft music, white roses, and quiet whispers. I sat in the third row, hands folded…

Human connection revealed through 300 letters between a 15-year-old killer and the victim’s nephew.

April asked her younger sister, Denise, to come along and slipped an extra kitchen knife into her jacket pocket. Paula…

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

On my wedding day, my in-laws mocked my dad in front of 500 people. they said, “that’s not a father — that’s trash.” my fiancée laughed. I stood up and called off the wedding. my dad looked at me and said, “son… I’m a billionaire.” my entire life changed forever

The ballroom glittered with crystal chandeliers and gold-trimmed chairs, packed with nearly five hundred guests—business associates, distant relatives, and socialites…

“You were born to heal, not to harm.” The judge’s icy words in court left Dr. Michael McKee—on trial for the murder of the Tepes family—utterly devastated

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

The adulterer’s fishing trip in the stormy weather.

In the warehouse Scott rented to store the boat, police found a round plastic bucket containing a concrete block with…

End of content

No more pages to load