In the rolling hills of Wilks County, Georgia, just southeast of Washington, the Whitaker Plantation once stood as a symbol of Southern prosperity and social order. Its stately columns and manicured grounds marked the wealth and influence of Colonel James Whitaker and his wife, Charlotte, whose family line traced back to the earliest days of the American republic. But beneath the surface of this genteel world, a story unfolded that would remain hidden for more than a century—a story of secrets, heartbreak, and the silent resilience of those forced to navigate the boundaries of race and family in the antebellum South.

The autumn of 1843 brought an event so rare that it made the society pages of the Augusta Chronicle: Charlotte Whitaker gave birth to triplets. The birth was celebrated publicly, recorded in church registries and local newspapers. Yet, behind closed doors, the fate of the third child was never mentioned. The official records showed only two sons—Thomas James and William Montgomery Whitaker—baptized and welcomed into the fold of Southern aristocracy. The third child vanished from public view, her existence erased from the family narrative.

The clues to this hidden chapter emerged slowly, pieced together from fragments of correspondence, church archives, and a battered household ledger discovered during courthouse renovations in 1962. The ledger, water-damaged but partially legible, contained not only lists of supplies and accounts, but curious notations about Ruth Anne Turner, Charlotte’s personal attendant. Ruth Anne’s monthly cycles were marked with small crosses in the margins, a detail that abruptly ended in January 1843—the month Charlotte likely discovered her pregnancy.

Ruth Anne herself was almost lost to history, her name appearing only in tax records and estate inventories. But a remarkable discovery in 1959 changed everything: a partial journal, written in phonetic English and attributed to Ruth Anne based on handwriting comparisons. Preserved in the Georgia Historical Society archives, the twelve pages of her account offer a rare glimpse into the events of that fateful September night.

According to Ruth Anne’s journal, Charlotte’s labor began shortly after midnight. Colonel Whitaker was away on business in Augusta, leaving the household in the care of Ruth Anne and the local midwife, Mrs. Abernathy. The birth of twins was anticipated, but when a third child arrived—small, quiet, and markedly darker than her siblings—Charlotte’s reaction was immediate and chilling. “This one never breathed. You understand?” she told Ruth Anne. “Take it away. Bury it deep where no one will find it.” But the baby cried when Ruth Anne wrapped her, and the attendant could not bring herself to follow Charlotte’s command.

Instead, Ruth Anne took the infant to her quarters, hiding her from the rest of the household. “Keep her quiet when people near. Feed her when I can slip away,” she wrote, her anxiety mounting as Charlotte’s suspicions grew. The last legible entry in the journal, dated about three weeks after the birth, reveals Ruth Anne’s desperate plan: “Colonel return tomorrow. Ms. Charlotte say she tell him I stole silver. Say they sell me south. I take the baby tonight. Northstar will guide.”

County records confirm that Ruth Anne Turner was reported as having run away in October 1843. A reward notice in the Augusta Chronicle offered $200 for her return, accusing her of theft but making no mention of a child. Around the same time, Charlotte Whitaker was treated by Dr. Harrison for “nervous exhaustion,” prescribed laudanum and bed rest as the household returned to its public routines.

The Whitaker twins became fixtures in local society, their presence noted in letters and church records. Yet, within the plantation, unease lingered. Staff turnover increased, and Charlotte’s correspondence reveals a growing preoccupation with security. Letters to her sister mention the hiring of a night patrol and reports of trespasses on the property’s edges. Colonel Whitaker’s business ledgers show substantial payments to a Pinkerton detective and the purchase of a remote cabin, maintained but never officially occupied.

Five years passed in apparent normalcy, until a fever swept through Wilks County in the autumn of 1848. Both twins fell ill, but only one survived. Strangely, confusion over which child lived and which died persisted in the records. Dr. Harrison’s diary notes Charlotte’s insistence that the surviving boy was William, though he had attended Thomas just the day before. The tutor’s records show the name Thomas crossed out and replaced with William. By January 1849, all documentation referred to William as the surviving twin.

Ruth Anne’s journal, partially recovered through conservation techniques, provides a haunting detail: the first boy “strong and loud,” the second “smaller with a small red mark behind his right ear.” Dr. Harrison’s medical records from 1843 confirm that William had such a birthmark, yet in 1848, the surviving child showed no sign of it. The ambiguity of the twins’ identities remains one of the story’s enduring mysteries.

After Colonel Whitaker’s sudden death in 1852—officially a riding accident, though rumors of suicide persisted—Charlotte assumed control of the estate. Her letters reveal increasing isolation and religious devotion, culminating in substantial donations to the church and a school for disadvantaged girls in Philadelphia. In 1858, a private investigator in Philadelphia was commissioned to search for a young woman of mixed race, accompanied by an older woman formerly of Georgia. The investigation’s results are lost to history, but payments continued until February 1859, shortly before Charlotte sold the plantation and moved to Savannah.

William Montgomery Whitaker married into a prominent Savannah family, his descendants remaining influential into the twentieth century. Yet, family correspondence donated to the Georgia Historical Society includes a letter in which William describes recurring dreams of “a woman I’ve never met with eyes so like my own, calling to me from across a great distance.” His mother dismissed these dreams as childhood fever, but William wondered if some deeper memory was trying to surface.

The story might have remained buried if not for a series of discoveries in the mid-twentieth century. During highway construction near the former plantation site in 1956, workers uncovered a small unmarked grave containing the remains of an infant estimated to have died in the 1840s. The grave was reinterred with a simple marker: “Unknown child c. 1840s.” In 1965, records from a Quaker settlement in Pennsylvania surfaced, noting the arrival of “RT from Georgia with infant daughter.” Further entries track Ruth Anne and her charge receiving literacy lessons, working as seamstresses, and eventually relocating to Canada in 1861 amid fears of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Did the third Whitaker child ever learn of her origins? Did she know about her brothers in Georgia? The historical record falls silent, but in 1876, a woman identified only as “E” placed an advertisement in a Savannah newspaper seeking information about the Whitaker family. The notice ran for three weeks and was never answered.

The psychological toll of these events is evident in the surviving records. Charlotte’s medical files show increasing dependence on sedatives and recurring nightmares. She reportedly spoke in her sleep of a child in the woods and someone watching from the trees. Colonel Whitaker’s role remains ambiguous, his personal correspondence destroyed after his death. His business ledgers show regular payments to investigators, but their purpose is never specified.

William Whitaker, the surviving twin—possibly Thomas, if the confusion in the records is to be believed—grew up under the shadow of these events. His school records describe an intelligent but troubled young man, prone to insomnia and melancholy. He excelled academically but struggled socially, haunted by dreams of a woman calling his name. After a brief stint at medical school, William withdrew, unable to bear the dissection rooms. “Upon uncovering the subject, a young colored woman, I was seized with such violent trembling that I had to be escorted from the room,” he wrote to his mother. He later became a successful lawyer, specializing in family estate matters.

The possible descendants of the third child remain untraced. If Ruth Anne and the infant girl reached Pennsylvania and later Canada, they likely changed their names and identities. Census records from Toronto in the 1870s list several mixed-race families from the United States, but none can be definitively linked to Ruth Anne or her charge. The trail grows cold at the Canadian border, obscured by time and the deliberate erasure practiced by many who escaped enslavement.

One tantalizing clue emerges in the form of a poetry volume published in Montreal in 1948 by Elellanena Turner. The poems speak of “Dreams of Cotton Fields I’ve Never Seen” and “Brothers Lost Across a Line I cannot cross.” The author’s biography states only that she was born in Toronto to parents from “farther south.” A poem titled “Georgia” reads: “In dreams I walk a red clay road to a house I’ve never entered, where my face looks back at me from portraits of strangers.” Is this mere coincidence, or could Elellanena Turner be a descendant of Ruth Anne and the third Whitaker child?

The physical landscape has changed dramatically. The Whitaker Plantation burned to the ground in 1879, long after the family had left. The land was parceled and sold, eventually becoming part of a state wildlife management area. Hikers occasionally find old brick foundations and, according to a 1966 newspaper account, a small stone marker surrounded by wild white roses. Forest Service employees have never located it again.

The psychological landscape is even more elusive. We can only imagine the pressures that drove Charlotte to deny her child, the courage that motivated Ruth Anne to risk everything, and the confusion experienced by the surviving twin. In antebellum Georgia, a child of mixed race born to a white mistress would have destroyed a family’s social standing. Charlotte’s position depended on maintaining boundaries that such a birth would irrevocably breach. Her increasing reclusiveness and dependence on sedatives suggest a woman haunted by her choices.

Ruth Anne’s journal reveals a woman of strength and moral conviction. Her final legible words, carefully transcribed by conservators, read: “They may erase us from their books but our blood still flows. Our story still lives. Northstar guide us now to where truth can breathe free.”

In 1958, a woman from Toronto visited the Wilks County courthouse, seeking information about the Whitaker family. The clerk remembered her striking gray-green eyes, reminiscent of the Whitaker family portraits. She asked directions to the old plantation site, then left a sealed letter on Colonel Whitaker’s grave through the groundskeeper, Mr. J. That night, a rainstorm washed the letter away, its contents lost to history.

The story of the Whitaker triplets is not just the tale of a single family, but of countless others whose lives were shaped and sometimes destroyed by the social structures of their time. The horror lies not in supernatural elements, but in the choices made under impossible pressure—the mother who rejected her child, the attendant who defied her mistress, the children who grew up never knowing their origins.

As night falls over the Georgia pines, one might imagine three children, separated by circumstance and society, yet forever connected by blood. One path ended abruptly in childhood. Another led to wealth and position in Southern society. The third disappeared into the North, perhaps flourishing in freedom, perhaps haunted by dreams of a home never seen.

The legacy of the Whitaker triplets lives on in archives and attics, in family resemblances and unexplained dreams. It reminds us that the past is never truly buried, but continues to shape the present in ways both visible and hidden. The true horror and beauty of this story lies in its unresolved nature, its gaps and silences, and the courage of those who chose compassion over convention.

In the end, the Whitaker triplets’ story challenges us to look more deeply at our own society, to question the boundaries we maintain, and to remember that every family has its secrets, every community its silences, and every narrative its omissions. The past breathes beneath the soil of the present, feeding roots that reach into our lives in ways we may never fully understand. The Georgia pines still whisper in the wind, and somewhere—perhaps even now—descendants of all three children live their lives, separated by choices made long ago, yet connected by bonds that transcend time and all human efforts to sever them.

News

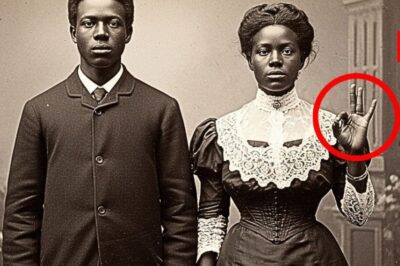

It Was Just a Portrait of a Young Couple in 1895 — But Look Closely at Her Hand-HG

The afternoon light fell in gold slants across the long table, catching on stacks of photographs the color of tobacco…

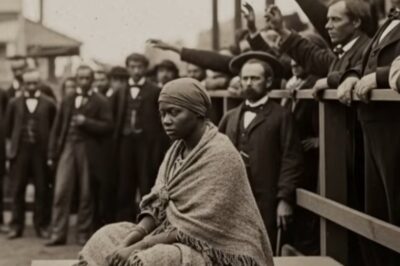

The Plantation Owner Bought the Last Female Slave at Auction… But Her Past Wasn’t What He Expected-HG

The auction house on Broughton Street was never quiet, not even when it pretended to be. The floorboards remembered bare…

The Black girl with a photographic memory — she had a difficult life

In the spring of 1865, as the guns fell silent and the battered South staggered into a new era, a…

A Member of the Tapas 7 Finally Breaks Their Silence — And Their Stunning Revelation Could Change Everything We Thought We Knew About the Madeleine McCann Case

Seventeen years after the world first heard the name Madeleine McCann, a new revelation has shaken the foundations of one…

EXCLUSIVE: Anna Kepner’s ex-boyfriend, Josh Tew, revealed she confided in him about a heated argument with her father that afternoon. Investigators now say timestamps on three text messages he saved could shed new light on her final evening

In a revelation that pierces the veil of the ongoing FBI homicide probe into the death of Florida teen Anna…

NEW LEAK: Anna’s grandmother has revealed that Anna once texted: “I don’t want to be near him, I feel like he follows me everywhere.”

It was supposed to be the trip of a lifetime—a weeklong cruise through turquoise Caribbean waters, a chance for Anna…

End of content

No more pages to load