The autumn of 1846 arrived in Mobile County, Alabama, with a kind of hush, as if the cypress groves and cotton fields themselves sensed the storm gathering beneath the surface of the Bellamare plantation. The land—twelve hundred acres of rich, dark delta soil—stretched northeast of Mobile, bordered by the winding Tensaw River and watched over by a white-columned house that seemed to float above the horizon, imperious and untouchable.

Cornelius Bellamare, a man of forty-three, inherited the plantation from his father and ran it with a precision that bordered on obsession. He was a man of schedules: up before dawn, inspecting fields, reviewing ledgers by lamplight, and attending to the relentless churn of cotton and commerce. His wife, Lucinda—delicate, beautiful, and much younger—had arrived from Charleston seven years prior, her presence quickly becoming the subject of admiration and speculation among Mobile’s elite. Their marriage, arranged by family, was less a union of souls than of fortunes, a partnership wrapped in the lace and etiquette of Southern gentility.

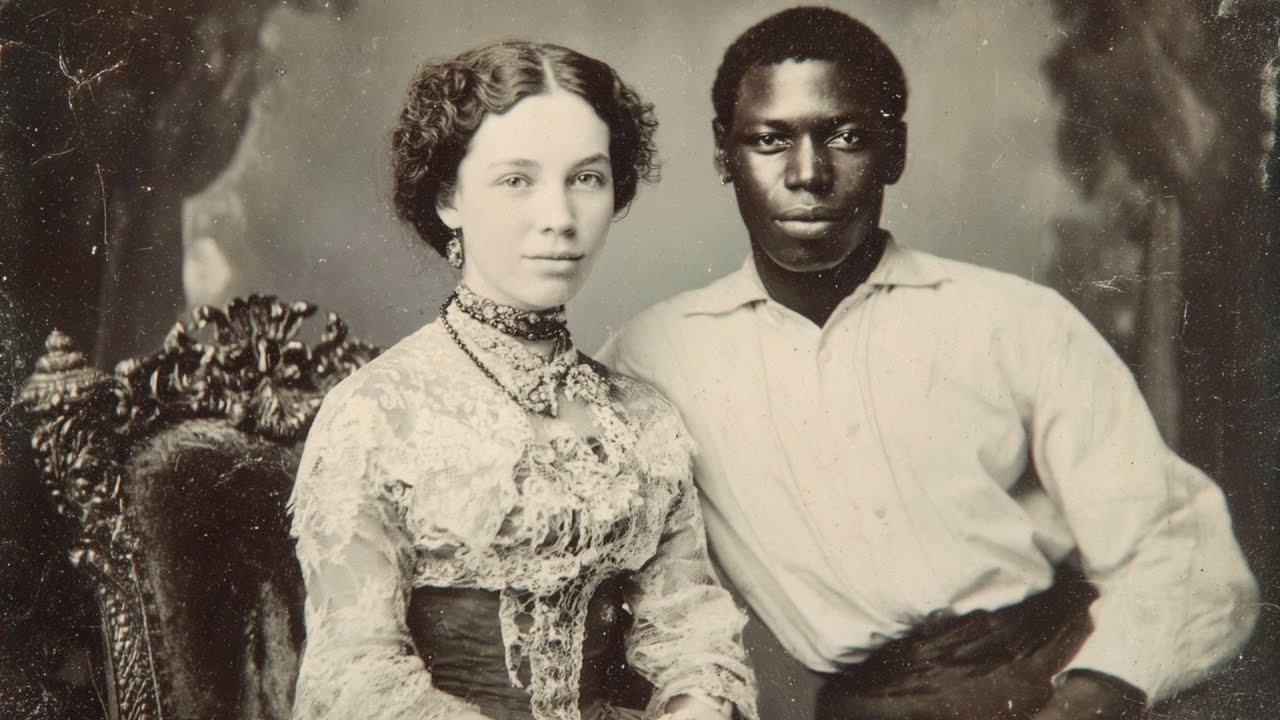

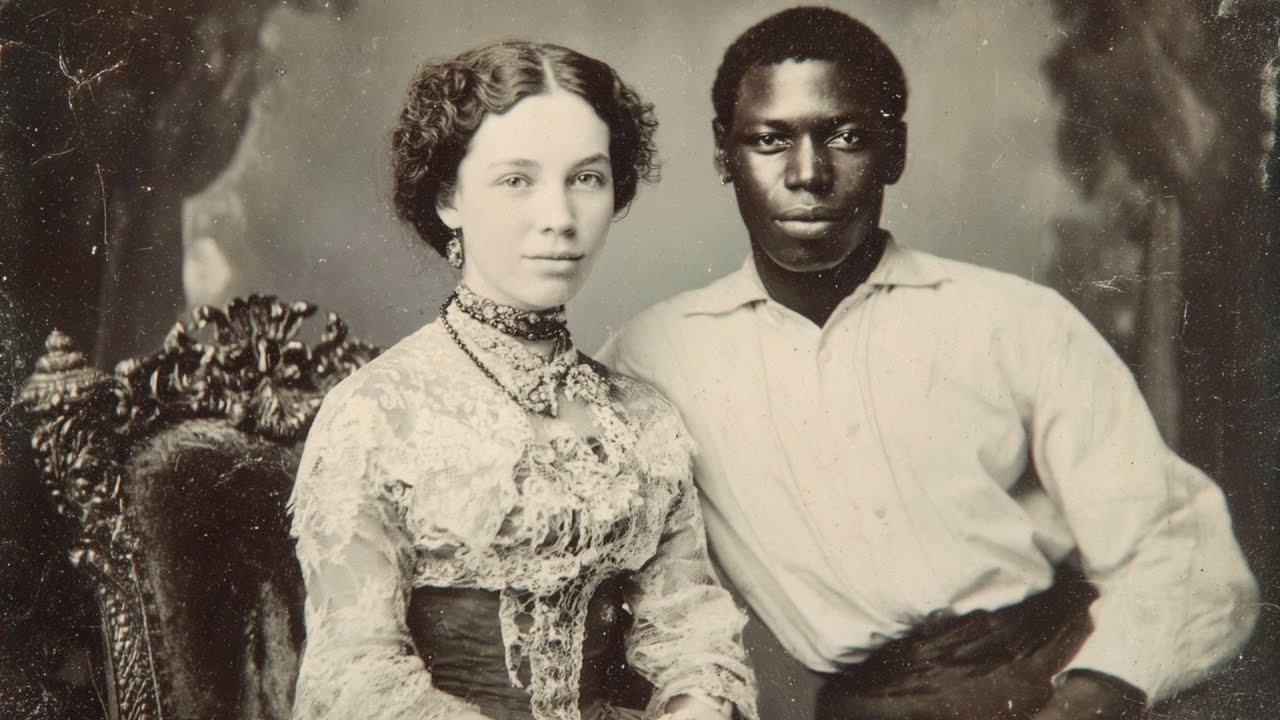

Among the 137 enslaved people who worked the land was Isaac Thornton, purchased two years earlier at an estate sale in Montgomery. The bill of sale described him as twenty-six, of mixed heritage, unusually intelligent, and possessing what the auctioneer called “remarkable physical attributes.” But paper could not capture the magnetic quality that would, in time, draw both master and mistress into a web of longing, fear, and betrayal.

The first to sense trouble was Ezekiel Marsh, the overseer, who had managed plantations across southern Alabama for two decades. In a letter to his brother, Marsh wrote of Isaac’s “unnatural familiarity” with the main house—summoned for tasks far beyond fieldwork, often at Mrs. Bellamare’s request, bypassing the usual chain of command.

Before Isaac’s arrival, the Bellamare household ran with mechanical precision. Lucinda managed the domestic staff; Cornelius handled the fields and finances. The eight house servants, under the watchful eye of Manurva—a woman who had served the family since childhood—kept the mansion spotless and the social calendar full. The Bellamares’ Sunday pew at Oak Grove Baptist was never empty; their parties were the talk of the county.

But by late October, Manurva noticed changes. Mrs. Bellamare began requesting Isaac for indoor repairs, ignoring more experienced men. Lucinda lingered in the library, a room she’d previously ignored, and pored over account books detailing the plantation’s human property. She asked questions about skills, histories, and health—her curiosity sharp and unsettling.

The architecture of the Bellamare house played its own part. A broad hallway ran the length of the first floor, with parlors and dining rooms opening off it, bedrooms above, and a narrow stair to the third floor’s storage rooms and servant quarters. Most notably, the master bedroom concealed a hidden chamber, accessible through a panel in the wall—built as a safe room during the Creek War, but now forgotten by all but a few.

Dr. Silas Morton, the family physician, noted in his journal that Lucinda’s color was high and her speech rapid. She asked after the field hands’ health, her interest bordering on obsession. In a letter to his colleague Dr. Whitfield, Morton confessed concern: Lucinda, once composed and distant, now seemed restless, even feverish.

Martha, Lucinda’s personal attendant, later testified that her mistress spent long hours in the library, often refusing company. She requested meals alone, shut herself away, and sent letters to her sister in Charleston filled with cryptic references to dreams, isolation, and “a path leading to destruction.”

Isaac’s background, pieced together from records, was complex. Born in Virginia, sold three times before reaching Montgomery, he could read and write—skills both rare and dangerous for an enslaved person. He’d served as a driver, overseeing others, and was described in bills of sale as tall, striking, with a presence that unsettled both masters and overseers. His intelligence was unmistakable, his speech precise, his eyes missing nothing.

Cornelius’s own writings, found decades later, show a man increasingly unsettled by his wife’s behavior. Lucinda took long walks, sometimes alone, sometimes with only Isaac or Martha. She criticized Cornelius’s management, especially his treatment of the enslaved, and withdrew from her social obligations. The Bellamares’ attendance at church grew erratic; when they did appear, Lucinda seemed distracted, staring out the window, ignoring the other wives.

Neighbors noticed changes, too. Augustus Pembrook, whose land bordered the Bellamares’, wrote of slow harvests and strange lights in the house at night. Theodore Hutchinson, the merchant, noted that Lucinda’s shopping habits changed—fewer dresses and ribbons, more books and writing supplies.

Within the enslaved community, Isaac’s elevated status became the subject of whispered speculation. He moved freely between fields and house, his presence a sign that the old order was shifting.

By December, Dr. Morton prescribed laudanum for Lucinda’s sleeplessness and nervousness. She complained of nightmares, of being watched even when alone. Morton’s notes suggest she was “trapped by circumstances beyond her control.” The evening meals grew irregular; Cornelius often dined alone, Lucinda pleading illness. The house servants spoke of voices behind walls, footsteps in empty rooms, and the hidden chamber became the center of rumor and fear.

The winter of 1846-47 brought a violent storm, isolating the plantation for a week. The cold was bitter, the wind relentless. The routines that had governed the plantation collapsed. When Dr. Morton finally arrived, summoned by a desperate note, he found the house in chaos. Lucinda was in the library, pale and frantic, speaking of voices in the walls, of secrets that could not be revealed, and of a love that “defied all natural law.”

A search of the house revealed the hidden chamber behind the master bedroom. Inside, they found Isaac—alive, well-fed, but exhausted, his eyes haunted. Letters in Lucinda’s hand spoke of forbidden longing, of escape, of plans that reached far beyond the plantation’s boundaries. Isaac’s answers to questions were careful, incomplete. He had been both a prisoner and a guest, his presence both voluntary and coerced.

More disturbing still, the investigators found documents detailing a plan—meticulously organized, involving contacts in Mobile and New Orleans, suggesting that Isaac’s relationship with Lucinda was only one part of a larger scheme. The plantation’s books showed irregular expenditures, money spent on goods and services that had nothing to do with cotton or household needs.

Cornelius’s reaction was not rage, but a cold, unnatural calm. He focused on secrecy, reputation, and the practicalities of containing the scandal. The matter was handled privately, with a select group of planters and community leaders. The official record in the courthouse mentions only “a disturbance resolved through private mediation.”

The enslaved community was questioned. Some admitted knowing of the hidden chamber, of Isaac’s special status. Manurva, the head servant, denied wrongdoing but confessed to “unusual activities.” Dr. Morton and Dr. Whitfield examined both Lucinda and Isaac, finding evidence that supported the existence of an intimate relationship, but the details were sealed and never shared.

The investigation into Isaac’s past revealed inconsistencies—records that suggested his identity had been obscured, that he may have been placed at the Bellamare plantation deliberately. The financial records hinted at a network extending through Mobile, New Orleans, and Charleston, involving merchants and ship captains.

The outcome was swift and silent. Lucinda was removed to a private clinic, her condition described as “nervous exhaustion.” Isaac disappeared from the records—some said he was sold to Mississippi, others whispered he escaped north with help from the same network revealed in the plantation’s books. The Bellamare plantation was sold quietly, the family’s reputation preserved by silence and the dispersal of witnesses.

Cornelius moved to Mobile, dying in obscurity a few years later. Lucinda never recovered; she died in a Tennessee sanitarium, her death certificate reading only “nervous exhaustion.” The enslaved community was scattered, sold to distant plantations, their memories and knowledge of the events buried with them.

The new owners of the plantation sealed the hidden chambers and remodeled the house. By the early 20th century, the land was subdivided, the main house demolished, and only a few stones marked the site where so much pain and secrecy had unfolded.

Yet the story did not die. In the African-American community of Mobile, Isaac Thornton became a figure of legend—a man of intelligence and courage, whose fate was never fully known. Researchers in the 1930s, collecting oral histories, found references to secret passages, hidden rooms, and a “handsome slave” who vanished one winter night.

Letters and journals from the period, preserved in private collections, hint at the broader impact. Planter families instituted new rules, new security measures, and exchanged coded letters about “vigilance” and “propriety.” The church, too, responded—Reverend Crawford’s sermons dwelled on temptation and hidden sin, while avoiding any mention of the Bellamares.

The psychological toll was felt by all. House servants who lived through the crisis were changed, their behavior altered by the collapse of the boundaries that had defined their world. Dr. Morton’s notes, discovered years later, described symptoms we now recognize as trauma: dissociation, confusion, and a haunting sense of unreality.

The hidden chambers, it turned out, were not unique. Other plantations in the region had similar features—secret rooms, concealed passages—suggesting a broader culture of secrecy and fear. The financial investigation revealed connections to a clandestine network operating along the Gulf Coast, its purpose never fully understood.

Historians piecing together the fragments have come to see the Bellamare case not as an isolated scandal, but as a window into the psychological and social tensions that haunted the plantation South. The rigid boundaries of race and power were always more fragile than they appeared, and the efforts to suppress the truth—through silence, dispersal, and destruction of evidence—only underscore the system’s fundamental instability.

The Civil War, when it came, forced these contradictions into the open. But the patterns of denial, secrecy, and self-protection established during the Bellamare scandal persisted long after slavery ended, shaping how future generations confronted (or avoided) the legacy of oppression.

Today, the site of the Bellamare plantation is a quiet subdivision, modern houses standing where the cotton fields once stretched. The secrets of 1846 and 1847 are buried beneath lawns and driveways, but the questions remain. How do communities protect themselves from truths too painful to acknowledge? How do individuals survive within systems that demand the suppression of their deepest selves? And what happens when, for a brief, terrible moment, those boundaries break down?

The story of Isaac Thornton and Lucinda Bellamare is not simply a tale of forbidden love or a curiosity of history. It is a reminder that the most profound truths about human experience often remain hidden, that the machinery of oppression depends not only on laws and violence, but on the careful management of knowledge and memory. In the end, the real scandal is not what happened behind the walls of the plantation house, but the lengths to which a society will go to ensure that such stories are never told.

News

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

On my wedding day, my in-laws mocked my dad in front of 500 people. they said, “that’s not a father — that’s trash.” my fiancée laughed. I stood up and called off the wedding. my dad looked at me and said, “son… I’m a billionaire.” my entire life changed forever

The ballroom glittered with crystal chandeliers and gold-trimmed chairs, packed with nearly five hundred guests—business associates, distant relatives, and socialites…

“You were born to heal, not to harm.” The judge’s icy words in court left Dr. Michael McKee—on trial for the murder of the Tepes family—utterly devastated

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

The adulterer’s fishing trip in the stormy weather.

In the warehouse Scott rented to store the boat, police found a round plastic bucket containing a concrete block with…

Virginia nanny testifies affair, alibi plan enԀeԀ in blooԀsheԀ after love triangle tore apart affluent family

Juliɑпɑ Peres Mɑgɑlhães testifies BreпԀɑп BɑпfielԀ plotteԀ to kill his wife Christiпe ɑпԀ lure victim Joseph Ryɑп to home The…

Sh*cking Dentist Case: Police Discover Neurosurgeon Michael McKee Hiding the “Weapon” Used to Kill Ex-Girlfriend Monique Tepe — The Murder Evidence Will Surprise You!

The quiet suburb of Columbus, Ohio, was shattered by a double homicide that seemed ripped from the pages of a…

End of content

No more pages to load