Savannah, Georgia, 1935. The city, still healing from the wounds of the Great Depression, wore its history in every cracked sidewalk and moss-draped oak. Grand antebellum mansions loomed over streets that remembered far more than their owners ever cared to admit. In Yamacraw, one of Savannah’s oldest neighborhoods, the past was not a distant echo but a living presence.

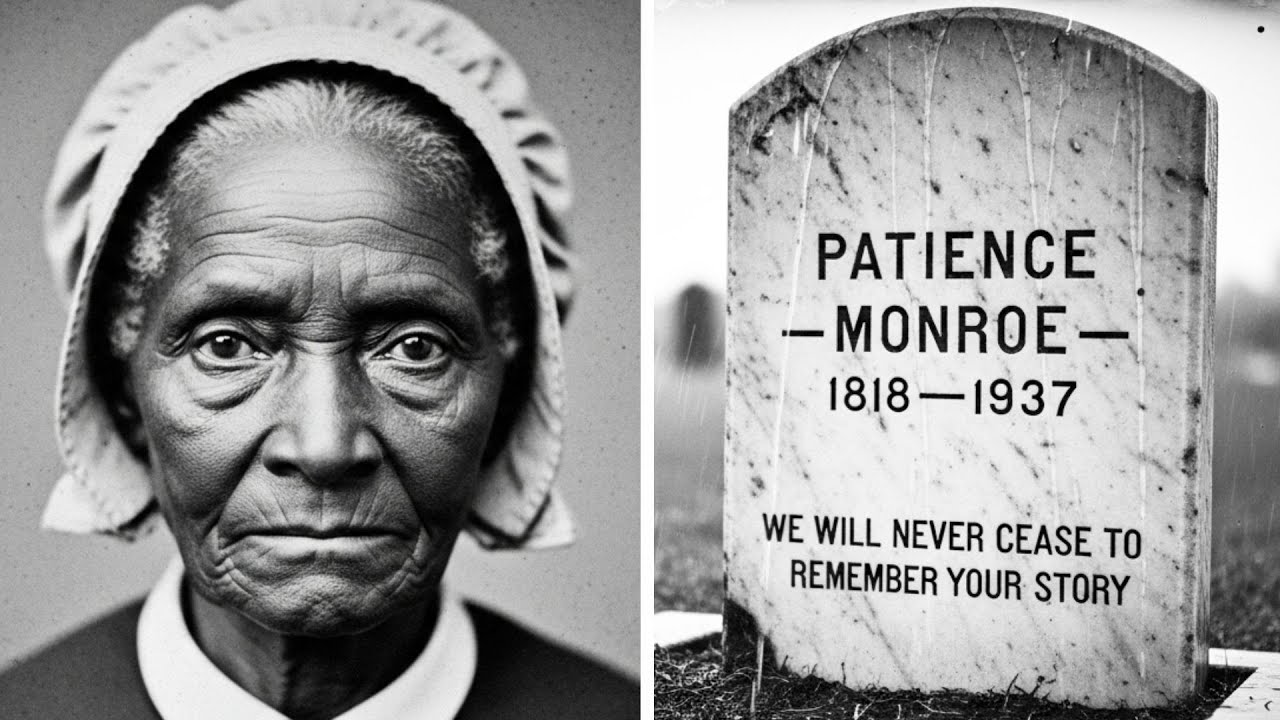

Patience Monroe was that presence. She lived in a weathered board cabin on the edge of the city, the kind of place that seemed to resist time itself. The boards were silvered by rain and sun, the tin roof rusted in patterns that mapped the years. Patience herself looked as if she had been carved by time—her body bent, her skin creased and dark, her eyes the color of amber whiskey, deep and unsettling. Children sometimes mistook her for a shadow until she moved. Adults, if they met her gaze, found themselves shifting, uncertain, as if her eyes saw through them.

She spoke rarely, her voice a hoarse whisper that forced listeners to lean in, to listen close. Her English was strange, old-fashioned, mingled with the rhythms of Gullah, the Creole tongue of the Sea Islands. Most people in Yamacraw knew her as “Miss Patience,” a fixture for as long as anyone remembered, but few knew the woman inside the cabin.

In November 1935, Dr. Eleanor Whitmore, one of Savannah’s few female physicians, was called to the cabin after Patience suffered a fall. Whitmore expected a routine visit. Instead, she found herself drawn into a mystery that would consume her.

“Her vital signs are incomprehensible,” Whitmore wrote in her diary that night. “Blood pressure abnormally low but stable. Heart rate barely above forty-five at rest. Body temperature two degrees below normal. By every indicator, she should be in shock or near death. Yet she is fully conscious and communicative.”

What disturbed Whitmore most were the scars. Patience’s body was a map of suffering: cross-hatched whip marks, burns, shackle scars layered over decades, healed fractures too numerous to count. Some marks, Whitmore estimated, were seventy years old or more.

During one rain-soaked evening, Patience spoke of her childhood. “I was born on Blackwood Plantation,” she said, her voice barely audible above the rain on the roof. “Mama’s name was Rose. She came from Africa. She never forgot the crossing. Told me about it every night, so it wouldn’t be forgotten.”

Whitmore leaned forward, notebook open. “What do you remember most clearly?”

Patience was silent so long Whitmore thought she’d drifted off. Then she spoke. “The smell of cotton. It gets into everything—your clothes, your hair, your skin. You breathe it in until you feel like your lungs are packed with it. And the heat. Summer in the fields was like standing in an oven. People died from it. Just dropped dead in the rows. The overseer would drag their bodies to the edge and make us keep working. Said it was a lesson about weakness.”

She paused, hands trembling. “But what I remember most is the singing. All day in the fields, we sang old songs from Africa nobody knew the words to anymore. We sang them anyway, because our mamas sang them and their mamas before them. Songs about rivers and mountains and freedom. We didn’t know the words, but we knew what they felt like. They felt like hope, even when there wasn’t any reason to hope.”

Whitmore returned again and again, learning more each time. Patience described being sold three times before age twelve, the auction block in Johnson Square, stripped and examined like livestock. “I was nine the first time I stood on that block. Wanted to die. Thought death would be better than that shame. But I never died, no matter how many times I wanted to.”

In December, Patience revealed something that changed Whitmore’s understanding. She spoke of her time on the Mercer plantation near Augusta. “Master Mercer enjoyed causing pain. Invented new punishments. Had a device called the stretcher—iron frame with chains. Shackle you spread eagle, leave you in the sun for days. No water, no food, no shade. I was put on that stretcher four times. Should have died every time. But I didn’t die.”

She fixed Whitmore with her amber gaze. “That’s when I started to understand something wasn’t right with me. Other people died from things I survived. Yellow fever swept through in ’32. Killed forty-three people in two weeks. I burned with fever so hot people said I glowed in the dark. But I didn’t die. Cholera came in ’39. Killed half the plantation. I suffered, but I didn’t die.”

“Perhaps you simply have a strong constitution,” Whitmore suggested.

Patience shook her head. “No, doctor. It wasn’t about strength. It was something else. Something that happened when I was a child. There was a woman on Blackwood, old African woman named Ayana. She was ancient even then. Took an interest in me because I was small, sickly. Everyone thought I’d die before I turned five.”

She paused, breath labored. “One night, Ayana took me to the swamp. Performed a ceremony. I don’t remember all of it. Tried for decades to recall exactly what she did, but parts are gone from my memory. Like my mind won’t hold on to them.”

“What do you remember?” Whitmore asked, torn between skepticism and fascination.

“I remember her speaking in a language I’d never heard. Cutting her palm and mine, pressing them together. Words I felt rather than heard, straight into my bones. And she told me something in English I’ve never forgotten: ‘You will carry the weight of your people. You will live to see the chains broken. You will remember what must not be forgotten. This is my gift and my curse to you.’”

Patience’s voice dropped to a whisper. “She died three days later. Just laid down one evening and never woke up. After that, I changed. Stopped getting sick. Started surviving things that killed others. Started remembering things differently. Not just my own memories, but others, like they were being added to mine.”

Whitmore felt a chill. “What do you mean, other people’s memories?”

“I remember things I never experienced. The middle passage, the hold of a slave ship, Africa. Places I’ve never been. Villages I’ve never seen. But the memories are there, clear as day, like they’re mine, even though they can’t be.”

“How many people’s memories do you carry?” Whitmore asked quietly.

“I don’t know. Dozens, maybe hundreds. Every time someone died near me, especially if they died badly, stories untold, I absorbed something of them. Their memories became part of mine. I carry the last thoughts of a woman named Sarah who was beaten to death for protecting her daughter. I carry the memories of a man named Jacob who was sold from his family and walked himself to death trying to get back. I carry the terror of children torn from their mothers, the rage of men broken by cruelty, the sorrow of women who endured unspeakable violations.”

She looked directly at Whitmore. “I am 119 years old, doctor, but I carry memories that span 200 years or more. I remember things that happened before I was born. I remember dying multiple times in different ways. And yet here I sit, still breathing, still remembering, unable to rest because the weight of all these stories presses down on me, demanding to be witnessed.”

“Why are you telling me this now?” Whitmore asked, her hands trembling.

“Because I can feel it ending. After all these years, I can feel death catching up. Those borrowed years, all those memories that aren’t mine, they’re demanding payment. Before I go, someone needs to know. Someone needs to understand what I’ve carried. Otherwise, all those people, all that suffering, disappears as if it never happened.”

Word spread through Savannah’s medical community. Dr. James Richardson, a prominent surgeon, insisted on examining Patience. “I’ve been practicing for thirty years,” he told Whitmore. “Never seen anyone live past 108. The idea she’s 117 is preposterous.”

But after examining Patience, his skepticism became fascination. “Her bone density is wrong. Calcification, wear patterns, vertebrae degradation—her skeletal system’s endured more than a century of gravitational stress. Her teeth—some look eighty years old, some fifty, as if her mouth aged at different rates.”

Richardson brought more equipment, ran more tests. “Her telomeres are severely shortened, consistent with extreme age, but the pattern is irregular. It’s as if parts of her aged at normal rates and others much more slowly. I have no explanation.”

What disturbed the doctors most was Patience’s eyewitness detail of historical events. She described the Nat Turner rebellion of 1831, the aftermath, the terror, the hangings. Every claim Whitmore checked matched historical records—even details of weather and crop conditions.

In March 1936, Whitmore met Professor Marcus Chen, a historian researching slavery in coastal Georgia. She expected skepticism but found enthusiasm. “We have records, bills of sale, census data, but very few first-person accounts from enslaved people. If her memories are accurate, she’s an unprecedented resource.”

Chen joined Whitmore in interviewing Patience, bringing maps and documents. Patience identified locations, recognized buildings, described people Chen could verify. “I was sold to Thaddius Blackwell in 1841. His plantation was on Ossabaw Island. That’s where I met Dinina from the Ebo tribe. She taught me remedies, songs, ways of remembering beyond just thinking about the past.”

Chen found a bill of sale from 1841: Patience, approximately twenty-three, sold from Augusta. The document existed.

“How is this possible?” Chen asked Whitmore. “Even with perfect recall, how can she remember details from ninety-five years ago? The human brain shouldn’t retain that for so long.”

Whitmore was quiet. “I think she’s telling the truth about absorbing other people’s memories. Somehow, she became a repository for experiences beyond her own. That’s what’s kept her alive so long.”

Through spring, Patience’s condition remained stable. She still walked, tended her garden, made remedies neighbors swore by. But her skin grew translucent, her eyes luminous, her weight dropped despite eating normally. More disturbing were episodes where she’d freeze, then speak in different accents, cadences, even languages—Gullah, West African dialects, Virginia tidewater, South Carolina low country.

“I’m in the rice fields,” she said once, voice higher, younger. “Water to my knees. Snakes everywhere. Mosquitoes so thick you breathe them in. My back hurts. I’m twelve and I want to die.”

Then her voice shifted, older, masculine. “They sold my son today. Took him from my arms. He was seven. I tried to hold on, but they beat me until I let go. I don’t know where they took him.”

Whitmore and Chen documented every episode. Each voice was distinct, emotional, carrying memories and pain. “I’m witnessing the death of a unique form of consciousness,” Whitmore wrote. “She is a collective, a repository of dozens or hundreds of lives preserved within a single vessel. Now that vessel is breaking down, and all those experiences are demanding expression before they’re lost.”

In June, Robert Harris, a young African-American journalist, arrived. “Miss Patience, I want to tell your story. Not just about how long you’ve lived, but what you’ve witnessed. With your permission, I’d like to write it down so others can know.”

Patience studied him. “Are you ready to hear things that will change how you see the world? Once you know, you can’t unknow. It becomes part of you.”

“I’m ready,” Harris said, though he wasn’t sure.

For three months, Harris visited daily, filling notebooks. Patience spoke of things history books omitted—sexual violence, systematic family separation, auction scenes. “They sold children away from mothers deliberately. It was control. Keep people grieving, easier to manage.”

“How did people survive this?” Harris asked once.

“We created our own world,” Patience said. “In the quarters, away from white eyes, we had community. Married each other, raised children, sang songs, told stories, practiced faith. Found joy where we could. We survived because we had each other and never forgot we were human, no matter how hard they tried to convince us otherwise.”

She spoke of resistance, overt and subtle. “Most resistance was quiet—working slowly, breaking tools, feigning illness, sabotaging crops, helping others escape even if you couldn’t yourself, teaching children to read though it was forbidden. Preserving culture, language, identity. That was resistance too.”

When Patience spoke of emancipation, her voice filled with wonder. “I was on a plantation near Savannah when the Union soldiers came. January 1865. Rumors of freedom for months, but we didn’t believe. Too dangerous to hope. One morning, blue uniforms, soldiers telling us we were free. I was forty-seven, enslaved my whole life. Suddenly, I was free. Didn’t know what it meant. For weeks, I just stood there, not knowing what to do, where to go, how to live. Freedom without means is its own kind of imprisonment.”

She described Reconstruction’s brief hope, then the crushing disappointment as new systems of oppression replaced old ones. “They couldn’t enslave us anymore, so they found other ways. Sharecropping, laws to criminalize black existence, forced labor. Terrorism, lynching, violence. The chains were gone, but the oppression continued.”

Harris published articles in the Atlanta Daily World. The response was polarizing—African-American readers grateful, white readers outraged. “No one wants to confront the full truth,” Harris told Whitmore. “They want to sanitize it, make it palatable. Patience’s testimony doesn’t allow that.”

By late 1936, Patience’s health declined. She was confined to her cabin, mind clear as ever. “The memories are separating,” she told Whitmore. “All these years, tangled together. Now they’re pulling apart. Distinct voices, distinct presences, preparing to leave.”

“Who is preparing to leave?” Whitmore asked gently.

“Everyone I’ve carried. All those people, their memories, gathering, pressing close, waiting for the end. I can feel them around me—Rose, Ayana, Dina, hundreds of others. They’re all here, ready to be released.”

On December 1st, Patience experienced a complete dissociative episode. For six hours, she cycled through dozens of personas—child, old man, young woman singing, grieving mother. Whitmore, Chen, and Harris documented everything.

“I don’t think she’s experiencing dissociative identity disorder,” Whitmore said afterward. “The personas are too distinct, too consistent with historical individuals. It’s as if she’s channeling different people, giving voice to memories stored within her for decades.”

Chen agreed. “Each persona spoke with knowledge specific to different periods and locations. This isn’t random confusion. It’s genuine historical memory.”

Harris looked at both. “So, she’s possessed by spirits?”

Whitmore replied, “Consciousness and memory may operate in ways we don’t understand. Traumatic experiences can leave imprints that persist beyond individual lives. Maybe Patience, through Ayana’s ceremony, became capable of absorbing and preserving those imprints. Whether supernatural or natural phenomenon we haven’t explained, I don’t know.”

In January 1937, Patience had a period of clarity. She sat up, stronger than she’d been in months. “I need to tell you something,” she said to Whitmore. “What it means to carry all these memories, all these lives.”

Whitmore sat, medical bag forgotten. “I’m listening.”

“It’s not just remembering their experiences,” Patience said. “It’s feeling their pain as if it’s happening now. Every whip strike, every violation, every terror and grief. I feel all of it constantly. For 119 years, I’ve carried the accumulated suffering of hundreds of people. Can you imagine what that does to a person? The weight, the relentlessness. But I also carry their joy. Love between people who weren’t supposed to love. Pride of parents watching children grow. Satisfaction of resistance. The hope that someday things would be better. I carry all of that too.”

“Why?” Whitmore asked quietly. “Why were you chosen?”

“Because someone had to. If no one remembered, all that suffering would be meaningless. Ayana understood that. She knew enslaved people couldn’t write their histories, couldn’t preserve their stories. She found a way to create a living archive. She found me.”

Patience reached out, took Whitmore’s hand. “Promise me something. Promise me what I’ve told you, what Robert has written, what Professor Chen has documented—promise me it won’t be forgotten. Promise me all these people I’ve carried, all these lives I’ve preserved, will be remembered.”

“I promise,” Whitmore said, tears streaming. “Your testimony will survive. The people you’ve carried will be known.”

Patience smiled, peaceful. “Then I can rest. After all these impossible years, I can rest.”

The clarity faded. Patience slipped back into the fragmented state, cycling through voices and memories. But now the episodes seemed purposeful, each memory given final expression before release.

The small cabin became a research station—medical equipment, recording devices, notebooks, historical documents. Martha Washington, Patience’s neighbor of forty years, assisted with care.

“Her eyes are changing, doctor,” Martha said. “Getting brighter, almost glowing. And when she talks in those voices, I swear I see different faces in hers, like she’s becoming other people.”

Whitmore confirmed it. Patience’s eyes had a strange luminescence, facial features shifting subtly during episodes. “This exceeds anything in medical literature,” Whitmore wrote. “Actual physical transformation, not just psychological. Bone structure shifts, skin tone changes, voice changes. I am witnessing something that challenges everything I understand.”

On January 28th, Patience spoke in a continuous stream for four hours. The voices flowed—Benjamin, sold from his family at eight; Ruth, bore eight children, watched seven sold, killed the eighth at birth; Solomon, escaped to Pennsylvania, died free after forty years in chains. Each brief, each heartbreaking, each a life history would have forgotten.

Chen, Harris, and Whitmore scrambled to record it all. “This is unprecedented,” Chen said. “First-person testimonies from dozens of individuals across the antebellum period. The historical value is incalculable.”

“It’s more than historical,” Harris said. “It’s spiritual. Final testimonies of people denied the right to speak. Patience is giving them voice.”

From a medical perspective, Whitmore added, “We’re observing the dissolution of an unprecedented form of consciousness. Patience Monroe hasn’t been one person for over a century. She’s been a collective, a repository. Now that collective is breaking apart, each component asserting its identity before dispersal.”

The stream continued through the night. Some testimonies were in English, others in Gullah, West African languages, dialects no one present could identify. As dawn broke, Patience fell silent, opened her eyes—her own again.

“They’re leaving,” she whispered. “I can feel them pulling away, returning to wherever such presences return. The weight is lifting. For the first time in longer than I can remember, I feel light.”

“How do you feel?” Whitmore asked gently.

“Peaceful,” Patience said. “After carrying so much for so long, peace feels extraordinary. I had forgotten what it was like to simply be myself.”

She thanked them all for bearing witness. “That was all I ever wanted. All Ayana wanted. For the stories to survive.”

Chen leaned forward. “Do you truly believe what happened to you was supernatural?”

Patience was quiet. “I believe there are aspects of consciousness and memory science hasn’t explained. Traumatic experiences leave imprints that can persist beyond lifetimes. Under certain circumstances, those imprints can be absorbed and preserved by someone whose consciousness is altered to receive them. Whether you call that supernatural or a natural phenomenon we don’t understand, I can’t say. But I know what I’ve experienced. I know what I’ve carried. It was real.”

Chen nodded. “Every verifiable detail she’s provided has proven accurate. Either she lived through these experiences and absorbed the memories, or we’re dealing with an elaborate fraud that would have required resources beyond what an illiterate former slave could have accessed.”

Whitmore added, “Her physical age exceeds anything in documented medical history. The pattern of aging is inconsistent with normal processes. The phenomena we’ve observed have no precedent. Either we accept something extraordinary has occurred or we dismiss evidence that meets every standard of scientific rigor.”

Harris put down his pen. “I’m not a scientist or a doctor. I deal in evidence and testimony. The evidence supports her account. Her testimony is consistent, detailed, and historically accurate. I believe her not because I need to believe in something supernatural, but because the facts demand it.”

Patience’s condition stabilized briefly, as if the separation of memories gave her a reprieve. She spoke more, now only as herself. She described life after emancipation, the challenges of freedom without resources, education, or family.

“I was forty-seven when the war ended. Too old to start over, too broken by decades of enslavement to adapt easily. Worked as a washerwoman, took in sewing, did whatever I could to survive. Never married. How do you build intimacy when you’ve been violated for decades? How do you trust when trust always led to betrayal?”

She spoke of Reconstruction’s hope, then its failure. “For a few years, it seemed things might change. Black men could vote, hold office, own property. We thought maybe the suffering had meant something. But it didn’t last. White people couldn’t accept equality. Used violence and terrorism to reimpose control. The federal government abandoned us. By 1877, it was like slavery had returned in everything but name.”

She described Jim Crow, segregation, violence. “They couldn’t enslave us anymore, so they found other ways. Separate schools, water fountains, everything. If you challenged it, they killed you. Lynching wasn’t just murder. It was terrorism meant to keep us afraid, compliant.”

Harris wrote every word. “Why did you stay in the South?” he asked. “Many migrated north for better opportunities.”

“Where would I go?” Patience replied. “By the time the migration began, I was in my seventies. Besides, I had a purpose here. The people whose memories I carried, most lived and died in Georgia. Their stories were rooted in this soil. Leaving would be abandoning them, abandoning the duty Ayana gave me. And as long as I lived here, as long as I existed as a reminder, the past couldn’t be buried or forgotten. I was that memory, walking around, refusing to disappear conveniently.”

In February, Dr. Samuel Hartwell from Emory University arrived, skeptical but curious. He ran tests—X-rays, blood analysis, tissue samples. “From a biological standpoint, this woman should be dead. Her body has exceeded every known limit of human longevity. The fact she’s conscious and communicative is inexplicable. And the reports of personality fragmentation, voice changes, absorption of memories—while I cannot verify those directly, they’re consistent with some form of consciousness operating differently from normal psychology.”

“So, you believe her claims?” Chen asked.

“I believe the evidence,” Hartwell said. “Something extraordinary has occurred here. That much is indisputable.”

Hartwell’s endorsement brought attention—journalists, curiosity seekers. Martha Washington and neighbors formed a protective barrier, allowing only researchers regular access.

In March, Patience described vivid dreams. “I dreamed about Blackwood Plantation. Saw it as it was when I was a child. The big house, the quarters, the fields. But it was empty. Just buildings and silence. I think it was showing me what’s left after everyone is gone. Hollow and meaningless without the people.”

She dreamed of Ayana, young and strong. “She told me the debt was settled, the duty fulfilled. She said I could rest now. All the people I’d carried understood what it cost me. They were releasing me.”

On March 18th, Patience asked to be taken outside. They carried her chair under an old live oak. She sat for hours, face turned to the sun, breathing in air, watching clouds, listening to birds. She began singing in a language none recognized.

“That’s Wolof,” Chen said quietly. “A West African language. She’s singing a spiritual, about rivers and crossing over, coming home.”

Patience finished, opened her eyes. “My mother taught me that song. She learned it from her mother, who learned it from women who came on the ships. It’s about the journey from life to death, returning to the ancestors. I’ve been singing it in my head for 119 years, but this is the first time I’ve sung it out loud.”

“What does it mean?” Harris asked.

“It means death isn’t the end. We return to the people who came before us, join the great community of ancestors. Suffering is temporary, the spirit is eternal. I’m going home. Finally going home.”

On March 25th, Whitmore found Patience awake. “Today is the day,” she said. “The last threads are breaking. The vessel is releasing what it’s held for so long.”

Whitmore sat beside her. “Are you afraid?”

“No,” Patience smiled. “I was afraid most of my life—of pain, violence, loss, never being free. But I’m not afraid anymore. I’m ready. I’ve lived long enough. Seen enough. Carried my burden. Fulfilled my duty. Now I can rest.”

Harris and Chen arrived. The four gathered, not as researchers but as witnesses. Patience drifted in and out of consciousness. When awake, she spoke inward, conversations with people only she could see.

“I see you, Mama,” she whispered. “You’re waiting for me. You look so young, so beautiful. Not worn down like I remember. You’re whole again.” She paused, listening. “Yes, I’m coming. I’m almost there.”

Around noon, she opened her eyes, looked at Whitmore. “Thank you for believing me. For documenting what I carried. For ensuring all those people won’t be forgotten.”

“It’s been my privilege,” Whitmore said, tears streaming.

Patience turned to Chen. “Use what you’ve learned. Teach the truth. Don’t let them sanitize or minimize it. Make them understand the full reality.”

“I will,” Chen promised.

She looked at Harris. “Keep writing. Keep telling the stories others want to bury. Your voice matters. Use it.”

“I will,” Harris said, voice breaking.

Finally, she looked at Martha. “Thank you for being my friend. For treating me like a person, not just a curiosity. For sitting with me through the long nights. I hope you find peace.”

Martha nodded, unable to speak through tears.

Patience closed her eyes. Her breathing slowed, intervals lengthening. Whitmore held her hand, monitoring her pulse, watching the gradual cessation of life. At 2:23 p.m., Patience Monroe took her last breath. It was gentle, undramatic—a breath not followed by another.

“She’s gone,” Whitmore said quietly.

They remained for several minutes in silence, feeling the weight of what they had witnessed. Whitmore gently closed Patience’s eyes, pulled the sheet over her face.

The coroner, Dr. William Pierce, arrived. He examined Patience’s body thoroughly. “This is the oldest person I’ve ever examined. The physical evidence supports extreme age far beyond normal human parameters. The wear patterns on her bones and teeth suggest decades beyond anything I’ve encountered. Tissue degradation consistent with age exceeding a hundred years. I cannot definitively prove she was 119, but I can say with medical certainty she was extraordinarily old. This case challenges our understanding of human longevity.”

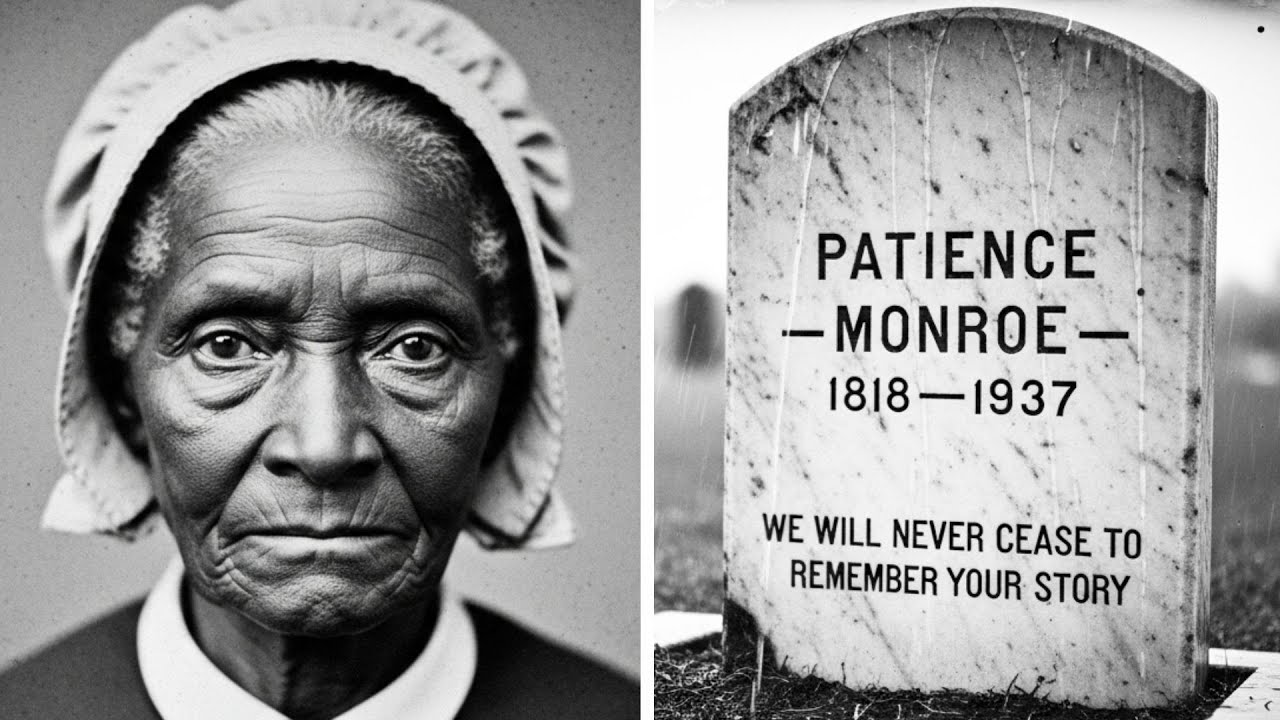

Patience was buried three days later in Laurel Grove Cemetery. Over 200 people attended—neighbors, researchers, elderly African-Americans, historians, journalists. Reverend Thomas Caldwell led the service.

“We gather today to honor a woman who carried more than any person should have to carry,” he said. “She lived through horrors we can barely imagine. Survived when survival should have been impossible. Remembered when forgetting would have been easier, and bore witness so that we would know, so that we would understand, so that we would never forget what was done to our people.”

“Patience Monroe was the last living person born into slavery in Georgia, perhaps the entire South. With her death, an era truly ends. No one left who remembers firsthand. No one left to testify from personal experience. Our duty is clear. We must preserve her testimony. Tell her story. Ensure the people whose memories she carried are not forgotten.”

Her gravestone read simply:

Patience Monroe

1818–1937

She remembered so we would never forget.

After her death, Whitmore compiled her notes, medical records, and observations into a manuscript: The Impossible Witness. Though rejected by medical journals, it circulated among researchers in consciousness studies and collective memory. Chen published historical articles, Harris wrote a book, The Last Witness, which became a foundational text in African-American literature.

By the 1970s, Patience Monroe’s story experienced a resurgence. Historians verified even more of her claims. Modern analysis of preserved hair and bone fragments showed patterns consistent with extreme cellular age, but definitive conclusions remained elusive.

What is certain: Patience Monroe existed. Birth records, sale documents, census records, a death certificate. She left behind testimony about the lived experience of enslavement. Multiple physicians documented her age and unusual phenomena. She dedicated her impossible life to ensuring suffering was remembered and resistance honored.

In Savannah, elderly residents still speak of the old woman who remembered everything, who carried the stories of her people, who refused to let the past be forgotten. The cabin where she lived stood for twenty more years, neighbors reporting strange phenomena—unexplained sounds, cold spots, a feeling of presence. When it was demolished, workers heard singing, old spirituals fading as the last boards came down. The land remained undeveloped for years, eventually marked as a historic site.

Whether Patience Monroe truly lived for 119 years, whether she absorbed memories through unknown means, whether Ayana’s ceremony altered her relationship with time and consciousness—these questions may never be answered. Science may one day explain what now seems impossible, or the mystery may remain forever unresolved.

But perhaps the more important question is not how she lived so long, but what she chose to do with that extended existence. She chose to remember, to preserve, to bear witness. She made her impossible life a repository for stories that would otherwise have died with their tellers. She honored people whom history tried to erase.

Her story challenges us to consider what we choose to remember, whose testimonies we value, whether we are willing to acknowledge that truth sometimes exceeds the boundaries of conventional proof. It reminds us that the greatest mysteries are not about the supernatural, but about the depths of human experience, the resilience of the spirit, and the lengths people will go to ensure truth survives, suffering is acknowledged, and the dead are not forgotten.

News

At my son’s wedding, he shouted, ‘Get out, mom! My fiancée doesn’t want you here.’ I walked away in silence, holding back the storm. The next morning, he called, ‘Mom, I need the ranch keys.’ I took a deep breath… and told him four words he’ll never forget.

The church was filled with soft music, white roses, and quiet whispers. I sat in the third row, hands folded…

Human connection revealed through 300 letters between a 15-year-old killer and the victim’s nephew.

April asked her younger sister, Denise, to come along and slipped an extra kitchen knife into her jacket pocket. Paula…

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

On my wedding day, my in-laws mocked my dad in front of 500 people. they said, “that’s not a father — that’s trash.” my fiancée laughed. I stood up and called off the wedding. my dad looked at me and said, “son… I’m a billionaire.” my entire life changed forever

The ballroom glittered with crystal chandeliers and gold-trimmed chairs, packed with nearly five hundred guests—business associates, distant relatives, and socialites…

“You were born to heal, not to harm.” The judge’s icy words in court left Dr. Michael McKee—on trial for the murder of the Tepes family—utterly devastated

The Franklin County courtroom in Columbus, Ohio, fell into stunned silence on January 14, 2026, as Judge Elena Ramirez delivered…

The adulterer’s fishing trip in the stormy weather.

In the warehouse Scott rented to store the boat, police found a round plastic bucket containing a concrete block with…

End of content

No more pages to load