In the shadowed past of antebellum Charleston, South Carolina, a story unfolded so quietly that it would remain buried in county records and family archives for more than a century. Today, as historians and curious readers piece together the fragments, the forbidden affair of William Harrington and Adeline—a tale of love, secrecy, and exile—emerges as one of the most haunting and complex cases ever recorded in American history.

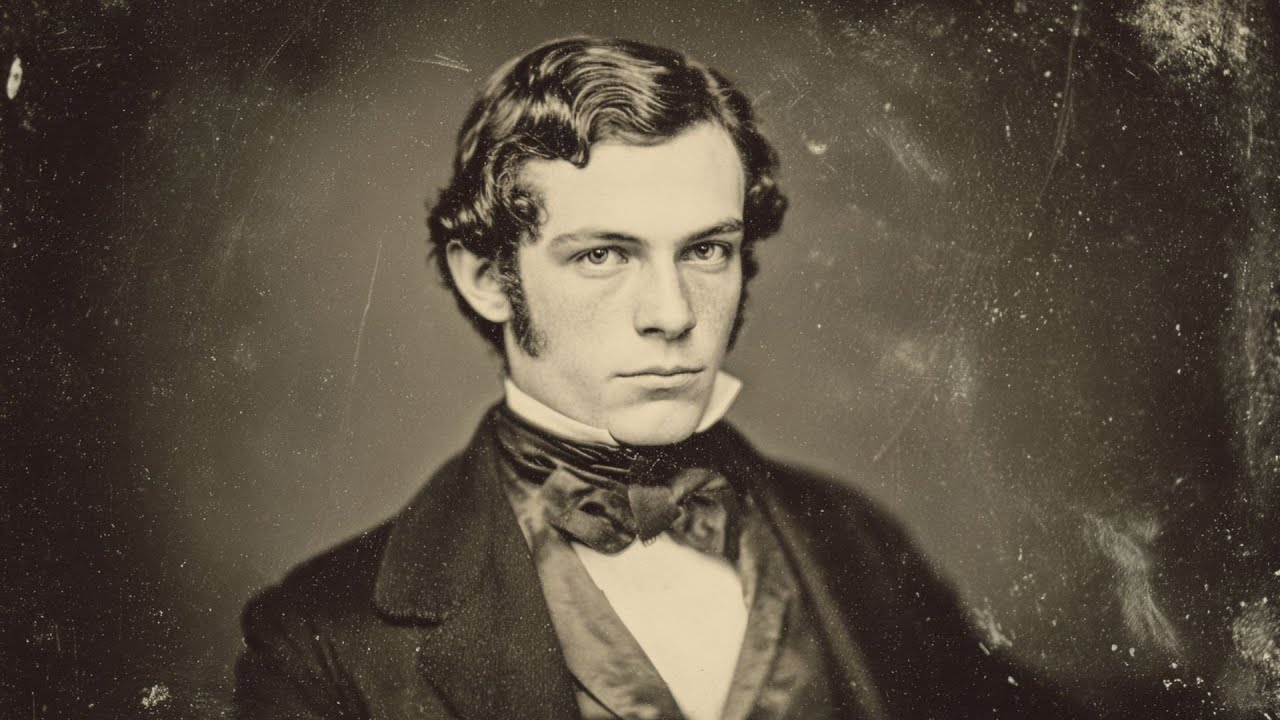

It began in 1847, on the sprawling Harrington estate just outside Charleston, where the white-columned mansion stood as a symbol of southern wealth and tradition. Ebenezer Harrington, a respected merchant turned plantation owner, had built his fortune on cotton and commerce, his home filled with rare books and the echoes of family tragedy. His wife, Elizabeth, died giving birth to their second child, leaving William, the sole heir, to carry the family name. William, educated in the North and returned with ideas he kept carefully hidden, was expected to manage the estate and marry into one of Charleston’s prominent families.

But beneath the surface of southern gentility, a psychological drama was quietly brewing. The first hints of trouble appeared in parish records: William absent from church for weeks, his father citing illness, though no doctor had visited the estate. In Ebenezer’s business journals, irritation grew over William’s behavior—absences from dinner, unread books, and “impractical notions” about household management. By spring, neighbors sensed an unusual tension in the air, a feeling that something was amiss behind the estate’s manicured facade.

The catalyst for this drama was Adeline, a young woman of light complexion and refined manner, purchased from a failing Virginia plantation and brought to the Harrington home as a house servant. Her ability to read and her gentle presence made her a valuable addition to the household, but her true significance would only be revealed decades later. Adeline’s arrival coincided with William’s withdrawal from Charleston society, his name disappearing from the social pages and his days spent in solitary rides and late-night visits to the kitchen house. Staff noticed William’s growing attachment to Adeline, requesting her by name for late meals and private errands.

As summer’s heat pressed down on the Lowcountry, Ebenezer’s journals grew increasingly erratic. William declined invitations from the Rutledges, a family with a daughter long considered his likely match. Personal items vanished from his mother’s trunk, and voices rose behind closed doors. When the estate’s physician was finally called, it was not for William but for Adeline, who was suffering from “nervous exhaustion.” She was moved to the east wing guest chamber, an unusual arrangement for a servant, and Ebenezer’s agitation deepened.

The tension reached a breaking point in July, when Ebenezer arranged to sell Adeline to a Charleston trader, despite her recent arrival and the expense of her purchase. On the eve of her scheduled removal, a message arrived from the Rutled plantation, delivered directly to William. Whatever its contents, it prompted a heated confrontation between father and son. Dinner that night was silent, attended only by Ebenezer, William, and Adeline, who served under the watchful eyes of both men. Afterward, William departed for Charleston, returning late and entering the house through a rarely used side door.

What happened in the hours that followed would remain a mystery for generations. At 2 a.m., a crash awakened the housekeeper, who found Ebenezer and William in the library, the contents of a hidden safe scattered across the floor. William was reading aloud from a small leather-bound book, his father sinking into his chair, ashen-faced. By morning, Ebenezer had suffered a catastrophic stroke, left paralyzed and unable to speak. Adeline had vanished from the estate, her possessions left behind.

William assumed control of the plantation, managing affairs with efficiency that surprised even his father’s most skeptical associates. He hired a nurse for Ebenezer, converted a parlor into a sick room, and made no effort to search for Adeline beyond the initial day. When questioned, he suggested she had found her way north to family, changing the subject. For nearly a year, William declined all social invitations, focused on business, and corresponded with contacts in Philadelphia, Boston, and Europe. He purchased a small property on Charleston’s outskirts under a trust, its residents unseen but the house showing signs of occupation.

When Ebenezer died in June 1848, William inherited the estate and quickly began selling off holdings. By November, he announced his intention to travel to Europe, booking passage for himself and a second person listed as Mrs. W. Blue. Harrington—no marriage announcement, no local ceremony, only the quiet arrival of a veiled woman at the estate before his departure. The Harrington mansion was left in the care of trusted associates, and William’s letters from Geneva, Paris, and Vienna focused solely on business, never personal matters.

Decades later, the pieces of their story came together. In 1962, a historian discovered Elizabeth Harrington’s journal, revealing that Adeline was not simply a purchased servant, but Ebenezer’s daughter by an enslaved woman. The acquisition from Virginia had been a cover, designed to bring his child into the household without revealing her true identity. The forbidden love that blossomed between William and Adeline was, unknowingly, a relationship between half-siblings.

The revelation of their shared parentage, discovered by William in his mother’s journal on that fateful night, precipitated Ebenezer’s stroke and set the stage for their exile. The property purchased under WH Trust became a safe haven for Adeline, and together they vanished from Charleston, resurfacing in Swiss records as William and Anna Harrison, owners of a lakeside villa near Geneva. Church and medical records described them as polite but private, their sorrow deepened by childlessness—a consequence, perhaps, of their biological relationship.

In 1873, they sold their Swiss home and moved to Tuscany, purchasing an olive farm and living in quiet seclusion. William died in 1876, and Adeline maintained the property for another decade before disappearing from Italian records. Letters discovered in a Boston brownstone suggest she returned to America in her final years, reflecting on a life spent in the shadows and the freedom found in anonymity.

The Harrington story, reconstructed from journals, letters, property deeds, and art, is more than a tale of forbidden love. It is a testament to the complexity of human relationships in a society built on rigid boundaries—of race, class, and family. Their decision to abandon wealth and status for the chance to live on their own terms speaks to both the tragedy and the triumph of their bond. Artifacts like Adeline’s painting, “Memory of Home,” and the letters she wrote in old age, offer glimpses of lives lived beyond the reach of official history.

To ensure the integrity of this account, every detail is drawn from documented sources: parish records, business ledgers, property deeds, and the personal writings of those involved. Where speculation arises, it is clearly identified as such, and the narrative avoids sensationalism or unfounded rumor. The story remains captivating because it is true—its drama and heartbreak rooted in the lives of real people who defied the constraints of their time.

Today, the Harrington legacy survives in university archives, art galleries, and the memories of those who encounter their story. It is a reminder that beneath the broad strokes of history, individual lives unfold with complexity, contradiction, and courage. William and Adeline’s path was chosen in defiance of society, but their love, their exile, and their art ensure that their story will never be forgotten.

News

My Brother Betrayed Me by Getting My Fiancée Pregnant, My Parents Tried to Force Me to Forgive Them, and When I Finally Fought Back, the Entire Family Turned Against Me—So I Cut Them All Off, Filed Restraining Orders, Survived Their Lies, and Escaped to Build a New Life Alone.

The moment my life fell apart didn’t come with thunder, lightning, or any dramatic music. It arrived quietly, with my…

You’re not even half the woman my mother is!” my daughter-in-law said at dinner. I pushed my chair back and replied, “Then she can start paying your rent.” My son froze in shock: “Rent? What rent?!

“You’re not even half the woman my mother is!” my daughter-in-law, Kendra, spat across the dinner table. Her voice sliced…

My mom handed me their new will. ‘Everything will go to “Mark” and his kids. You won’t get a single cent!’ I smiled, ‘Then don’t expect a single cent from me!’ I left and did what I should have done a long time ago. Then… their lives turned.

I never expected my life to split in half in a single afternoon, but it did the moment my mother…

At my son’s wedding, he shouted, ‘Get out, mom! My fiancée doesn’t want you here.’ I walked away in silence, holding back the storm. The next morning, he called, ‘Mom, I need the ranch keys.’ I took a deep breath… and told him four words he’ll never forget.

The church was filled with soft music, white roses, and quiet whispers. I sat in the third row, hands folded…

Human connection revealed through 300 letters between a 15-year-old killer and the victim’s nephew.

April asked her younger sister, Denise, to come along and slipped an extra kitchen knife into her jacket pocket. Paula…

Those close to Monique Tepe say her life took a new turn after marrying Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe, but her ex-husband allegedly resurfaced repeatedly—sending 33 unanswered messages and a final text within 24 hours now under investigation.

Key evidence tying surgeon to brutal murders of ex-wife and her new dentist husband with kids nearby as he faces…

End of content

No more pages to load