There are stories buried deep in the American South, stories that sleep beneath the cotton fields and riverbanks, stories that pulse in the soil long after the names have faded. Some are too painful to tell, too monstrous to believe. But every so often, the past claws its way out of the archives, demanding to be seen, refusing to let the dead be forgotten.

In the Alabama State Archives, a leather journal sat untouched for 127 years. When it was finally opened in 1974, the discovery sent shockwaves through the quiet halls of history. Three seasoned archivists, men and women who had spent careers cataloging the ordinary and the tragic, requested immediate transfers. They could not bear to read what was inside. The author was a doctor—Nathaniel Morrison—who had been called to a plantation outside Selma in 1847. What he documented was not simply slavery. It was something colder, more calculating—a system so methodical and so cruel that it warped everyone it touched, even the family who built it.

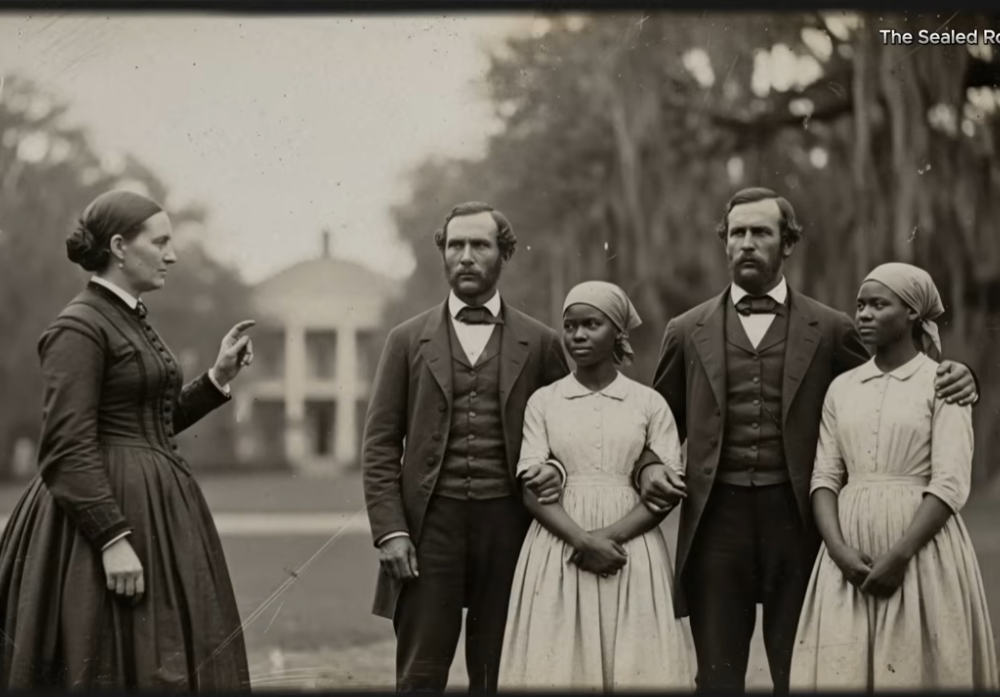

Willowmir Plantation, nestled on 8,400 acres along the Alabama River, was once the pride of Dallas County. Its black soil grew cotton as if the river itself was pumping wealth into the ground. Colonel Marcus Crane, who purchased the land in 1809, was a man of reputation and ambition. By 1825, Willowmir was producing hundreds of bales each year, and Marcus was a respected figure among the Southern elite. He married Elizabeth Thornton, a clever young woman from Montgomery, in a union born of necessity as much as affection. Together, they had six children, three of whom survived: Jonathan, Samuel, and Mary.

Their lives were shaped by the rigid codes of plantation aristocracy—French tutors, scripture lessons, and the unspoken understanding that they were superior to the enslaved people who worked the land. This was the world Elizabeth inherited when Marcus died suddenly in 1842, leaving her not just a widow but the steward of a legacy teetering on the edge of ruin.

The truth of Marcus’s finances surfaced in a lawyer’s office in Selma. Willowmir, on paper, was worth a fortune—but Marcus had borrowed heavily, gambling on land and railroads, buying more enslaved people on credit. The debts were crushing, and Elizabeth, at 38, faced the prospect of losing everything: her home, her status, her children’s future. The lawyer, Horus Pean, offered a cold solution. If she could increase production—extract more labor, more profit from the 63 enslaved people she now owned—she might keep Willowmir. But there would be no new purchases, no capital to spare. The only way forward was to make her “resources” multiply.

Most plantations relied on natural increase. Enslaved women had children, and those children became workers. But Elizabeth did not have decades. She had four years before the largest note came due. She needed rapid, systematic growth. She needed a breeding program.

The idea did not come all at once. It crept in through sleepless nights and ledger calculations, through the cold arithmetic of survival. Elizabeth began tracking the women at Willowmir, noting their ages, health, and fertility. She selected eleven of the youngest and strongest, moving them into a cabin near the main house. She watched her sons—Jonathan, 19, and Samuel, 16—boys trapped by duty and circumstance. She saw them not as children, but as tools.

The first conversation with Jonathan was a study in coercion. Elizabeth explained the financial crisis, the need for “maximum efficiency.” She told him his participation was necessary. Jonathan recoiled, horrified, but Elizabeth pressed on. “You understand your duty to this family,” she said. “You will help me or watch your sister starve.” Jonathan was trapped—no education, no prospects beyond Willowmir. He complied, entering the cabin where Celia, an eighteen-year-old woman born at the plantation, awaited. Celia was given no choice. Compliance meant better food, lighter work, safety for her family. Resistance meant punishment, separation, or sale to the deadly cane fields of the Deep South.

What happened in that cabin was not romance, not even the common brutality of masters taking enslaved women. It was scheduled, recorded, optimized for profit. Elizabeth tracked cycles, assigned partners, and moved Jonathan along her list as soon as a pregnancy was confirmed. Samuel, more volatile and easily manipulated, joined the program soon after. He accepted his role with chilling ease, convinced by his mother that this was a privilege, a right of ownership.

By the end of 1843, Elizabeth’s system was running with clinical precision. The selected women lived under direct supervision. Jonathan and Samuel rotated among them, pregnancies were monitored, and incentives—better food, lighter work—were offered not as kindness but as investments. A healthy baby was worth $400 by age twelve. A dead infant was a loss of capital.

The horror of Willowmir was not just in the violation of enslaved women, but in the corruption of Elizabeth’s own sons. Jonathan retreated into silence and drink, his spirit eroded by guilt. Samuel became cruel, expanding the program beyond Elizabeth’s control, violating women outside the cabin, embracing violence as a way of life.

Amidst this darkness, there were witnesses. Bethany, a cook who could not read or write but possessed a formidable memory, began keeping mental records. She remembered dates, names, conversations—building a testimony in her mind, knowing that written records would never survive. She understood that memory itself was resistance.

In 1844, resistance erupted. When Sarah, the sixteen-year-old daughter of Jacob the blacksmith, was selected for the program, Jacob refused. He stood his ground, risking everything to protect his child. The overseer, Mills, threatened violence, but Jacob held firm. Elizabeth responded with calculated cruelty, threatening to sell Sarah to the hell of Louisiana’s cane fields unless Jacob publicly apologized and ensured her compliance. Faced with the impossible choice—violation or death—Jacob broke. The system absorbed his resistance, turning love into another weapon.

The breeding program grew. By 1845, eighteen women were confined to the cabin. Jonathan and Samuel had fathered twenty-three children. Elizabeth’s ledgers tracked each birth, each future profit. She began planning for generations, matching children by desired traits, designing a population that could be trained for skilled work.

Dr. Morrison, the plantation doctor, visited Willowmir regularly. He had witnessed the brutality of slavery before, but the systematic nature of Elizabeth’s program shocked him. She showed him her ledgers, proud of her efficiency. Morrison wrote in his journal: “May God forgive me for not burning this, but someone must know what I witnessed, even if that knowledge comes a century after my death.” He documented everything—the schedules, the pregnancies, the psychological destruction of Jonathan and Samuel, the trauma of the women.

Resistance simmered beneath the surface. Ruth, one of the selected women, began providing false information about her cycles, sabotaging the program’s efficiency. Clara, working in the main house, tampered with Elizabeth’s records. Isaiah, an elder assigned to maintenance, orchestrated subtle sabotage—broken equipment, damaged crops. These acts, though small, began to unravel the system.

Jonathan reached his breaking point in 1847, withdrawing completely, missing scheduled sessions, and eventually fleeing Willowmir for Selma. Samuel, left to maintain the program alone, became increasingly violent and unpredictable. Naomi, one of the women, was beaten so severely by Samuel that she miscarried. Dr. Morrison, appalled, confronted Elizabeth, but she dismissed his concerns. Morrison left Willowmir, refusing to participate any longer.

Without Morrison’s medical care, the program faltered. Women and infants died at higher rates. The economic engine Elizabeth had built began to collapse. The enslaved population, emboldened by their sabotage, worked slowly and carefully, maintaining just enough productivity to avoid severe punishment.

In March 1848, the supervised cabin burned to the ground. No one died, but the message was clear: the enslaved people had moved from passive resistance to active destruction. Elizabeth rebuilt, but the cabin burned again. Other acts of sabotage continued—equipment disappeared, crops were damaged, overseers were attacked. Elizabeth’s power was waning.

Desperate, Elizabeth ended the breeding program. The cabin was demolished, the women returned to field work, her sons removed from management. Willowmir reverted to a conventional plantation. The enslaved people understood—they had won a victory, not freedom, but the destruction of a specific evil. Bethany added a final entry to her mental records, remembering the fires, the sabotage, the coordination that forced Elizabeth’s surrender.

The aftermath was as haunting as the system itself. The children born through the program grew up at Willowmir, visible evidence of the Crane family’s legacy. Elizabeth tried to erase the history, selling older children to distant plantations, destroying ledgers, burning documentation. But memory survived. Bethany told her story to the Freedmen’s Bureau after emancipation, naming names, preserving testimony.

Jonathan died in Selma, consumed by guilt and despair. Samuel was exiled to Texas, dying violently in 1859. Elizabeth, paralyzed by a stroke, was cared for by Mary, who burned the remaining ledgers in an attempt to protect the family’s reputation. Bethany watched, knowing that oral history was now all that remained.

Elizabeth Crane died in 1856, buried without fanfare. Willowmir was sold, operated as a conventional plantation until the end of slavery. The formerly enslaved people dispersed, some staying in Dallas County, others heading north. Bethany joined the Freedmen’s Bureau, testifying about her experiences, ensuring that the story would survive.

Dr. Morrison’s journal, sealed for a century, was finally opened in 1974. Its detailed account, combined with Bethany’s testimony and oral histories, reconstructed the horror of Willowmir. The story became public, sparking debate, pain, and reflection. For descendants, the revelation was both recognition and trauma—a history that could not be undone, but could finally be named.

Willowmir was not unique. Similar systems existed elsewhere, but Elizabeth Crane’s innovation was to systematize the breeding of enslaved people, applying business logic to violation. The story forces us to confront uncomfortable truths: slavery was not just labor exploitation, but the systematic destruction of families and identities. Even familial bonds could be corrupted by the logic of ownership.

Today, the land where Willowmir stood is farmland. Cotton still grows in the soil where horror once thrived. There is no marker, no memorial, nothing to indicate what happened. But the evidence survives—in archives, in memories, in the stories that refuse to die.

This story is not entertainment. It is testimony. It demands remembrance, not for the sake of the dead alone, but for the living—for those who carry the legacies of trauma and resistance, for those who must learn to recognize evil in its many forms. Elizabeth Crane believed her system was rational, necessary, justified. She was wrong. Her confidence in her own righteousness is a warning, a reminder of how easily horror can be rationalized when it serves our interests.

The obligation to remember is real. Bethany spent her life preserving memory because she understood: testimony is power. Memory is resistance. The act of remembering, even when documentation is destroyed, is a form of justice—imperfect, incomplete, but necessary.

If you have read this far, you are now a witness, too. You know what happened at Willowmir. You know the names, the suffering, the resistance. Share this story. Let it challenge your assumptions. Understand that systems of oppression do not disappear; they evolve. The first step in fighting them is to bear witness.

The truth is patient. It waits in archives, in memories, in stories that refuse to be forgotten. What happened at Willowmir Plantation was real. The resistance was real. The aftermath was real. And the obligation to remember is yours now, too.

Thank you for bearing witness. Thank you for not looking away. Because the alternative to difficult truth is comfortable lies—and comfortable lies are how evil persists.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load