For generations of TV fans, Hogan’s Heroes has been a staple of classic American comedy. Families gathered around their sets in the 1960s, laughing at the antics of Colonel Hogan and his crew as they outwitted the bumbling Nazi officers of Stalag 13. But behind the laughter and slapstick, the show holds secrets that most viewers never imagined—stories of survival, resilience, and a quiet rebellion against hatred that makes Hogan’s Heroes far more than just a sitcom.

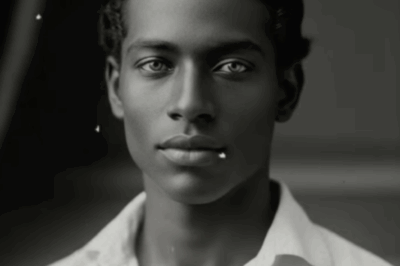

Imagine tuning in every week, seeing Werner Klemperer as the perpetually flustered Colonel Clink, John Banner as the lovable Sergeant Schultz, and Robert Clary as the cheerful Corporal LeBeau. Their performances made the Nazis look foolish, harmless, and utterly incapable. But for the actors themselves, these roles were deeply personal. Many had faced the horrors of Nazi Germany firsthand, and for them, comedy wasn’t just entertainment—it was a weapon.

Werner Klemperer, who brought Colonel Clink to life, knew intimately the pain that the Nazis inflicted. His father was a renowned orchestra conductor in Germany, and the family was forced to flee the country as the Nazi regime targeted Jewish families. Though they escaped, the trauma lingered. When Werner accepted the role of Clink, he insisted that his character always be portrayed as a buffoon—the opposite of the menacing Nazi officer. He wanted every laugh at Clink’s expense to be a laugh at the Nazis themselves, a subtle act of defiance against the regime that had destroyed so many lives.

John Banner, famous for his “I know nothing, nothing!” catchphrase, also carried scars from the Nazi era. He had lived through the rise of Hitler in Europe and understood the terror that swept through ordinary lives. Banner’s famous line wasn’t just a funny quip—it reflected how many people, frightened and powerless, chose to “know nothing” about the injustices around them. Schultz’s willful ignorance became a bittersweet commentary on history, and Banner’s performance gave that line a depth few viewers realized.

Then there’s Robert Clary, whose story is perhaps the most astonishing. Before he played Corporal LeBeau, Clary survived the unimaginable: he was imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp during World War II. The courage it took to step onto a set and relive, even in parody, the experience of being a prisoner is extraordinary. Through his role, Clary reclaimed his narrative, transforming pain into laughter for millions and showing that humor can be a powerful act of healing and resistance.

These actors weren’t just reading lines—they were channeling real experiences, using comedy to fight back against the darkness they had known. Their performances were layered with meaning, turning Hogan’s Heroes into a quiet tribute to hope and resilience. The show became a beacon that even in the darkest times, laughter and friendship could survive.

But the secrets of Hogan’s Heroes go beyond the cast. When the show finally aired in Germany—25 years after its original run—it was reimagined as “Barbed Wire and High Heels.” The German version exaggerated the foolishness of the Nazi characters, giving them thick country accents and even adding a girlfriend for Colonel Clink to make him seem less threatening. These changes were designed to ensure that German audiences saw the series as pure comedy, not a painful reminder of their history.

Even the theme song has its own hidden story. The catchy tune that opens every episode originally had patriotic lyrics celebrating brave soldiers, but producers decided to keep the words secret, opting for instrumental music instead. This choice maintained the show’s delicate balance—honoring real heroes while keeping the tone light for families at home.

The show’s creators also had a playful side, deliberately inserting mistakes into episodes. Modern wristwatches, advanced cigarette lighters, and other anachronisms popped up in scenes set during World War II. These weren’t slip-ups—they were winks to the audience, reminders that Hogan’s Heroes was meant to entertain, not educate. The goal was to keep the show fun and accessible, while still respecting the sacrifices of real soldiers.

And then there’s the fate of the Stalag 13 set. When the series ended in 1971, the elaborate set sat empty on the CBS lot. In 1974, it was used for the controversial film Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS—a movie that explored the darkest aspects of Nazi concentration camps. In a symbolic twist, the set was destroyed in a fiery explosion for the film’s climax. For fans, watching Stalag 13 go up in flames was like seeing childhood memories erased. The destruction was a stark reminder of the real horrors of war, contrasting sharply with the show’s message of hope and humor.

Werner Klemperer’s hidden musical talent is another layer in the show’s rich tapestry. Though Colonel Clink was infamous for his terrible accordion and violin playing, Klemperer was actually a gifted musician. Producers had to ask him to play badly on purpose, so the character’s incompetence would shine through. In rare moments, his real skill would slip out before he quickly returned to Clink’s signature screeching.

Some of the show’s most iconic moments were unscripted. John Banner’s “I know nothing” wasn’t in the original script—it was an inspired ad-lib that became the series’ defining line. Bernard Fox, meanwhile, played two completely different characters—Colonel Rodney Kittinden and an unnamed German general—showcasing his remarkable versatility. Most viewers never noticed these subtle shifts, just as they missed the running joke of Colonel Clink’s perpetually unlit cigar—a symbol of his insecurity and desire to appear powerful.

The cast’s creativity extended beyond the screen. They recorded a comedy album, “Hogan’s Heroes Sing the Best of World War II,” performing wartime songs in character. Imagine Sergeant Schultz crooning “Beer Barrel Polka” or Colonel Clink attempting a love ballad—it was a hilarious, surreal extension of the show’s spirit.

Richard Dawson, known for his role as Corporal Newkirk, originally auditioned to play Colonel Hogan. When producers felt his American accent wasn’t quite right, Dawson switched to a British accent—first trying a thick Liverpool style before settling on a more accessible London accent. Even small choices like this shaped the show’s unique flavor.

Props had meaning, too. General Burkhalter’s rare Mercedes convertible was more than just a car—it was a symbol of Nazi leaders’ obsession with power and status. Only 57 of those cars existed, underscoring the character’s arrogance and the show’s attention to detail.

Perhaps the most surprising secret is that Hogan’s Heroes almost took place in an American prison. The original concept featured a clever inmate outsmarting the warden, but a last-minute pivot moved the setting to a German POW camp. That change gave the show its heart, allowing it to honor Allied soldiers and transform a story of captivity into one of courage and laughter.

Looking back, Hogan’s Heroes is much more than a simple comedy. It’s a layered work of art, created by people who survived unspeakable hardships and chose to turn their pain into joy. The actors used their experiences to fight back against hatred, the writers balanced respect and entertainment, and even the smallest details carried meaning. The show’s “dark truth” is actually a story of hope: that laughter can be a powerful weapon, and that even in the face of evil, humor and kindness can prevail.

Every time Colonel Hogan outsmarts his captors, every time Sergeant Schultz chooses to “know nothing,” every time Colonel Clink fails at being intimidating, viewers are witnessing more than comedy—they’re seeing real people who transformed trauma into triumph. The next time you watch Hogan’s Heroes, remember the secrets behind the laughter, and know that every joke was a small victory for hope and humanity.

News

After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer walked into my office and smugly handed me divorce papers, saying, “She’ll be taking everything—the house, the cars, and full custody. Your kids don’t even want your last name anymore.” I didn’t react, just smiled and slid a sealed envelope across the desk and said, “Give this to your client.” By that evening, my phone was blowing up—her mother was screaming on the line, “How did you find out about that secret she’s been hiding for thirteen years?!”

Checkmate: The Architect of Vengeance After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer served me papers at work. “She gets…

We were at the restaurant when my sister announced, “Hailey, get another table. This one’s only for real family, not adopted girls.” Everyone at the table laughed. Then the waiter dropped a $3,270 bill in front of me—for their whole dinner. I just smiled, took a sip, and paid without a word. But then I heard someone say, “Hold on just a moment…”

Ariana was already talking about their upcoming vacation to Tuscany. Nobody asked if I wanted to come. They never did….

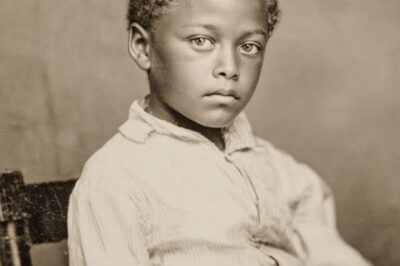

The Impossible Mystery Of The Most Beautiful Male Slave Ever Traded in Memphis – 1851

Memphis, Tennessee. December 1851. On a rain-soaked auction block near the Mississippi River, something happened that would haunt the city’s…

The Dalton Girls Were Found in 1963 — What They Admitted No One Believed

They found the Dalton girls on a Tuesday morning in late September 1963. The sun hadn’t yet burned away the…

“Why Does the Master Look Like Me, Mother?” — The Slave Boy’s Question That Exposed Everything, 1850

In the blistering heat of Wilcox County, Alabama, 1850, the cotton fields stretched as far as the eye could see,…

As I raised the knife to cut the wedding cake, my sister hugged me tightly and whispered, “Do it. Now.”

On my wedding day, the past came knocking with a force I never expected. Olivia, my ex-wife, walked into the…

End of content

No more pages to load