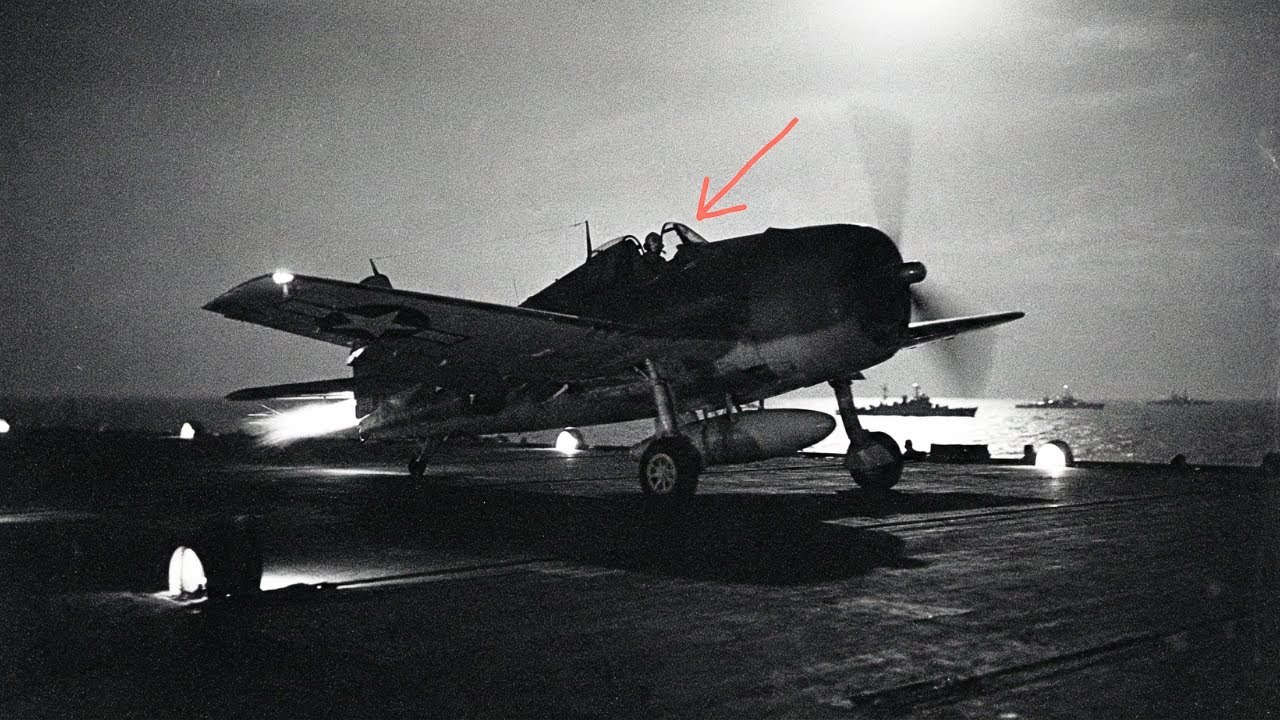

November 13th, 1943. USS Essex, Philippine Sea. 0347 hours. Aviation machinist’s mate Second Class James Sweat watches another F6F Hellcat cartwheel off the carrier deck into the black Pacific waters. That’s the third pilot lost this week—not to Japanese Zeros, not to anti-aircraft fire, but to their own fuel tanks exploding during night carrier landings. The statistics are catastrophic. Since October, Task Force 38 has lost 47 Hellcat pilots to fuel vapor explosions during carrier recoveries. The self-sealing fuel tanks designed to save pilots from enemy gunfire are killing them instead.

Every hard landing, every arrested hook catch sends a shock wave through the fuel system. The vapor ignites. The cockpit becomes an inferno before the pilot can even release his harness. Admiral Mark Mitcher has grounded all night operations. Without night fighter capability, the carrier group is blind after sunset.

Japanese torpedo bombers are exploiting this vulnerability. Last week, the USS Independence took two torpedoes during a midnight attack. Seventy-three sailors died. The ship barely made it back to Pearl Harbor. The Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics has been working on the problem for eight months.

Their solution: reinforce the tank mounting brackets, add dampening springs, modify the filler cap pressure release. It doesn’t work. Pilots keep dying. The fuel tanks keep exploding. What the admirals don’t know, what nobody knows, is that a 24-year-old mechanic from Terre Haute, Indiana has been conducting unauthorized experiments in Hangar Bay 3.

James Sweat never graduated high school. He has no engineering degree, no formal training in fuel system design. He’s not supposed to be thinking about solutions. He’s supposed to be following orders, turning wrenches, keeping his head down. But Sweat has been watching the crash investigations, studying the burn patterns, and he’s noticed something the engineers missed.

Something so obvious, so simple, that when he finally explains it to the brass, they’ll accuse him of sabotage. They’ll threaten him with court martial. They’ll tell him his idea violates three separate Navy regulations and could get him twenty years in Leavenworth. Three hours from now, Sweat is going to steal a Hellcat off the flight deck. He’s going to fly an unauthorized test mission in the middle of a combat zone, and he’s going to prove that everything the Navy knows about fuel tank safety is wrong.

The F6F Hellcat entered service in January 1943 with a revolutionary promise. It would be the first carrier fighter that could survive combat damage and bring pilots home alive. The secret was the self-sealing fuel tank. When a bullet punctured the tank, a special rubber lining would automatically seal the hole. The Japanese Zero had no such protection.

One burst from a Hellcat’s guns would turn a Zero into a fireball. American pilots would walk away from damage that killed their enemies. By summer 1943, the Hellcat was dominating Pacific combat. Kill ratios reached 19 to 1. Pilots loved the aircraft—it was fast, heavily armed, nearly indestructible in dogfights.

The Navy ordered 5,000 more. Then the night operations began. Carrier landings have always been dangerous. Pilots call it a controlled crash, slamming a 20,000-lb aircraft onto a pitching deck at 90 knots, hoping the arresting wire catches your tail hook. During daylight, pilots can see the landing signal officer, judge their approach angle, adjust for the carrier’s movement.

At night, they’re landing blind, guided only by a few dim lights and radio calls. The first fuel tank explosion occurred on October 3rd, 1943. Lieutenant Robert Anderson made a textbook night landing on the USS Lexington. His tail hook caught the number three wire. The sudden deceleration sent a pressure wave through his fuel tanks.

The vapor ignited. Anderson died before the fire crew could reach him. The Navy blamed pilot error. Anderson must have come in too fast, hit too hard. They ordered pilots to make gentler approaches.

October 14th, 1943. Ensign Charles Murphy dies in an identical explosion on the USS Bunker Hill. Murphy’s approach was perfect. His landing speed was exactly by the book. October 22nd. Lieutenant James Fleming, USS Enterprise. Same explosion, same result.

October 29th. Two pilots in one night—USS Essex and USS Yorktown. The Bureau of Aeronautics convenes an emergency investigation. Their engineers identify the problem: the arresting wire deceleration creates a hydraulic hammer effect inside the fuel tanks. The liquid fuel slams forward, then rebounds backward.

This creates a pressure spike that ruptures the self-sealing rubber lining. Fuel vapor escapes into the tank’s airspace. Any spark from static electricity, metal-on-metal contact, or the electrical system ignites it. The bureau’s solution seems logical: reinforce everything. Add stronger mounting brackets to prevent the tanks from shifting, install dampening springs to absorb the shock, modify the pressure relief valves to vent vapor more quickly.

They retrofit 200 aircraft with the new system. November 6th, 1943. The first aircraft with the new modifications explodes during landing. Lieutenant Richard Best dies instantly. The admirals are desperate.

Admiral Mitcher grounds all night fighter operations indefinitely. Without night air cover, the carrier groups are vulnerable. Japanese submarines have already sunk two destroyers. Torpedo bombers attack with impunity after dark. Intelligence reports indicate the Japanese are massing their submarine fleet for a coordinated night assault on the carrier groups.

The Navy’s top fuel system engineers—men with degrees from MIT and Caltech—are stumped. They’ve tried everything: stronger tanks, better venting, shock absorption. Nothing works. The consensus is clear. Self-sealing fuel tanks and carrier night operations are fundamentally incompatible.

The Navy will have to choose one or the other. In hangar bay 3 of the USS Essex, aviation machinist’s mate Second Class James Sweat is not convinced. He’s been watching the investigations, studying the wreckage, and he thinks everyone is looking in the wrong place. Sweat grew up fixing tractors on his family’s Indiana farm during the Great Depression. He never finished high school, had to drop out at sixteen when his father died, leaving him to support his mother and three younger sisters.

He worked at a Terre Haute auto repair shop, became known locally as the kid who could fix anything. When Pearl Harbor was bombed, Sweat enlisted the next day. The Navy didn’t want him as a pilot—no high school diploma meant no officer training. They made him a mechanic instead. Sweat didn’t complain; he loved working on aircraft.

The F6F Hellcat was the most complex machine he’d ever touched. Nine cylinders, 2,000 horsepower, hydraulics, electrical systems, weapons. He studied every manual he could find. He volunteered for every training course. Within six months, he could disassemble and reassemble a Hellcat engine blindfolded.

But Sweat wasn’t just a wrench turner. He watched how things failed. When other mechanics saw a broken part, Sweat saw a pattern. When engineers proposed solutions, Sweat mentally tested them against what he’d observed in the field. The night of November 12th, 1943, Sweat is assigned to crash investigation duty.

Lieutenant William Edwards has just died in another fuel tank explosion. Sweat examines the wreckage in the hangar bay. The fuel tanks are ruptured exactly like all the others. The mounting brackets, reinforced with the Navy’s new modifications, are intact. The dampening springs are undamaged.

The pressure relief valves functioned perfectly. Sweat stares at the blackened tanks for three hours. Then he notices something. The explosion originated at the top of the tank, not the bottom. The burn patterns show the fire spread downward, but fuel is heavier than air—it pools at the bottom of the tank.

If the hydraulic hammer effect was sloshing fuel forward and creating vapor, the explosion should start at the bottom where fuel and air mix—unless the problem isn’t the fuel at all. Sweat grabs a flashlight and crawls inside the wreckage. He examines the tank’s interior. The self-sealing rubber lining is intact at the bottom, but at the top, near the filler cap, the rubber is shredded—not burned, shredded, torn apart by mechanical force before the fire started.

Sweat realizes what’s happening. The engineers are solving the wrong problem. The hydraulic hammer isn’t creating dangerous vapor by sloshing liquid fuel—it’s creating a vacuum. When the aircraft decelerates violently, the fuel slams forward, leaving an empty space at the back of the tank. Nature abhors a vacuum.

Air rushes in through the filler cap to fill the void. But the self-sealing rubber lining, designed to be flexible, gets sucked inward by the vacuum. It tears, and when it tears, it creates static electricity. That spark ignites the fuel vapor that’s always present in any partially filled tank. The Navy’s solution—reinforcing the tanks—makes the problem worse.

Stronger tanks mean more violent vacuum effects. Better pressure relief valves vent vapor faster, creating stronger vacuums. Sweat knows how to fix it, but nobody’s going to listen to a mechanic without a high school diploma. November 13th, 1943. Hangar Bay 3. Sweat can’t sleep.

He keeps seeing Lieutenant Edwards burning alive in his cockpit. He thinks about the solution. It’s so simple, so obvious. Fill the empty space in the fuel tank with something that prevents vacuum formation. Something inert that won’t burn, something that expands and contracts with the fuel level—foam rubber.

If you line the inside of the tank with open-cell foam rubber, it will soak up fuel like a sponge when the tank is full. As fuel burns off during flight, the foam releases it gradually. But most importantly, the foam fills the empty space. No empty space means no vacuum. No vacuum means no tearing of the self-sealing liner.

No tearing means no static spark. The foam would add maybe five pounds to each tank. It wouldn’t affect performance. It wouldn’t require any structural modifications. You could retrofit it in an hour.

Sweat finds Chief Petty Officer Michael Torres in the maintenance office. Torres has been a naval aviator for fifteen years. He trusts Sweat’s instincts. “Chief, I need foam rubber about six cubic feet and I need access to a Hellcat’s fuel system.” Torres looks at him. “What for?” “I know why the tanks are exploding and I know how to fix it.”

The Bureau of Aeronautics has fifty engineers working on this. They’re looking in the wrong place. Torres considers this. He’s seen Sweat solve problems before. “Show me.”

They work through the night in a corner of the hangar bay. Sweat explains the vacuum theory. He shows Torres the burn patterns from the crash investigations. He demonstrates with a bucket of water and a rubber sheet how the vacuum tears the lining. Torres is convinced. “We need to test this. I need a Hellcat and I need to do a full throttle arrested landing simulation.”

“That’s impossible. We can’t just take an aircraft without authorization.” “Then we get authorization from who? The air boss, the CAG? They’ll laugh us out of the room. You’re a machinist’s mate, second class. You’re not even an engineer.” Sweat knows Torres is right. The Navy has a rigid hierarchy. Ideas flow down, not up. The enlisted mechanic doesn’t tell admirals how to design fuel systems.

“What if we just do it?” Sweat says quietly. “Do what?” “Take a Hellcat tonight. Install the foam. Run a test landing. If it works, we have proof. If it doesn’t, I’ll take the court martial.” Torres stares at him. “That is absolutely illegal. You’d be stealing a naval aircraft. That’s twenty years in Leavenworth. Maybe a firing squad.”

“How many more pilots are going to die while we wait for permission?” Torres thinks about Lieutenant Edwards, about the seventy-three sailors who died on the Independence, about the Japanese submarines circling the carrier group waiting for darkness. “I’ll get the foam rubber,” Torres says. “You get the Hellcat ready. We test at dawn.”

November 13th, 1943. Sweat and Torres work frantically in the pre-dawn darkness. They’ve selected Hellcat number 42, a reserve aircraft that’s not scheduled for morning operations. Using mattress foam from the ship’s stores, cut into strips and soaked in fire retardant, they line the interior of both fuel tanks. The installation takes forty minutes.

They don’t have time for ground tests. They don’t have time for calculations. They barely have time to button up the access panels before the morning flight operations begin. “I’ll fly it,” Torres says. “No, my idea, my responsibility.” “You’re not a pilot.” “I’ve got thirty hours in the co-pilot seat. I know how to land this thing.” Torres knows this is insane, but they’re out of time. “Make it quick. One landing, then we bring this to the CAG.”

Sweat climbs into the cockpit. The flight deck crew is preparing for morning operations. In the chaos of aircraft movements, one more Hellcat taxiing to the catapult doesn’t attract attention. Sweat’s heart is pounding. He’s never launched from a carrier before, never landed on one. He’s about to attempt the most dangerous maneuver in naval aviation with an unauthorized fuel system modification.

The catapult officer waves him forward. Sweat advances to the catapult. The launch crew hooks the holdback. Sweat runs through the checklist from memory. Flaps down. Mixture rich. Prop full forward. Canopy locked. The catapult fires. The acceleration slams Sweat back into his seat. Three seconds later, he’s airborne, climbing away from the Essex at 200 knots.

For ten minutes, Sweat circles the carrier group. He burns off fuel, getting the tanks down to half full—the same level that caused the explosions. His hands are shaking. He’s committed about six court martial offenses in the last hour. If this doesn’t work, his Navy career is over.

He lines up for landing approach. The landing signal officer guides him in. Sweat cuts power, drops flaps, adjusts his angle. The carrier deck rushes up. His wheels slam down. His tail hook catches the number two wire. The deceleration is violent—zero to ninety knots in two seconds. Sweat feels the fuel surge forward in the tanks. He waits for the explosion. Nothing happens. He’s alive. The tanks are intact. The foam worked.

Sweat taxis to the parking area and shuts down the engine. As he climbs out of the cockpit, he sees Commander David McCampbell, the air group commander, striding across the flight deck with six officers behind him. McCampbell’s face is crimson with rage. “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” The confrontation happens right there on the flight deck with two hundred sailors watching.

“Sir, I can explain.” “Explain. You stole a naval aircraft. You conducted an unauthorized flight operation. You endangered this entire carrier group.” Torres steps forward. “Sir, if you’ll just listen—” “I’ll have you both in the brig within the hour.” The room erupts. Other officers are shouting. The deck crew has stopped working to watch. Someone yells for the master at arms.

Sweat tries to explain about the foam, about the vacuum theory, but McCampbell won’t listen. Then Captain Raul Waller, the Essex’s commanding officer, arrives on the flight deck. “Commander McCampbell, what’s the situation?” McCampbell explains, “Unauthorized flight, stolen aircraft, violation of about forty Navy regulations.” Waller turns to Sweat. “Why?”

Sweat explains everything—the vacuum theory, the torn rubber linings, the foam solution, the successful test landing he just completed. The flight deck goes silent. Waller looks at the Hellcat. “You modified the fuel tanks?” “Yes, sir.” “Without authorization?” “Yes, sir.” “And you just completed a full throttle arrested landing with half full tanks?” “Yes, sir.”

Waller walks to the Hellcat. He examines the fuel tank access panels. He calls over the ship’s engineering officer. They inspect the foam installation. Five minutes later, Waller turns back to Sweat. “Machinist’s mate Sweat, you’re either going to prison or you’re going to save this fleet. We’re going to find out which. Commander McCampbell, ground all flight operations. Get me the Bureau of Aeronautics on the radio and get me ten more Hellcats ready for modification.”

If you’re fascinated by stories of ordinary people who changed history through courage and ingenuity, consider subscribing to Last Words. We bring you the untold stories of heroes who refuse to accept the impossible. Hit that subscribe button and ring the notification bell so you never miss an episode.

The Bureau of Aeronautics responds within hours. Captain Raul Waller’s message—“Enlisted mechanic may have solved fuel tank explosion problem”—reaches Admiral John McCain, commander of Task Force 38. McCain orders immediate testing. November 14th, 1943, USS Essex conducts controlled experiments. Six Hellcats are modified with foam-lined fuel tanks. Six control aircraft retain standard tanks.

Each aircraft performs ten arrested landings at various fuel levels, various approach speeds, various sea states. The test pilots push the limits—hard landings, off-center catches, maximum deceleration. The results are conclusive. Zero explosions in the foam-lined aircraft, two explosions in the control group. But the Navy brass remains skeptical.

Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman, head of carrier aviation development, flies out to the Essex personally to interrogate Sweat. “You’re telling me that fifty engineers from MIT missed something a farm boy from Indiana figured out?” “I’m not an engineer, sir. Maybe that’s why I saw it. I wasn’t looking at equations. I was looking at wreckage.”

Sherman examines the test data. He interviews the test pilots. He inspects the foam installation. Finally, he asks the question that matters: “What’s the operational impact? Weight, performance, maintenance?” Sweat has the answers ready. Five pounds per tank—negligible. No performance degradation in flight tests. Installation time forty-five minutes per aircraft. Cost eight dollars in materials.

Sherman makes his decision. “We’re implementing this fleetwide. Every Hellcat in the Pacific gets the modification within two weeks.” But there’s a problem. The Navy doesn’t have enough foam rubber. The material is in short supply. Most of it goes to life jackets and flotation gear.

Sherman requisitions every pound of suitable foam in the Pacific theater. It’s not enough. Then someone suggests mattresses. Every ship has hundreds of mattresses. The foam inside them, if treated with fire retardant, could work. Within seventy-two hours, sailors across the Pacific Fleet are cutting up mattresses. They’re sleeping on bare springs while their mattress foam saves pilots’ lives.

Nobody complains. Everyone knows someone who died in a fuel tank explosion. The modification program becomes the fastest aircraft retrofit in naval history. By November 30th, 1943, over 800 Hellcats have foam-lined fuel tanks. Admiral Mitcher lifts the night operations ban.

December 4th, 1943. The first combat test. Task Force 38 is operating near the Gilbert Islands. Japanese intelligence has located the carrier group. At 2030 hours, radar picks up incoming aircraft—twelve Mitsubishi G4M Betty torpedo bombers approaching from the northwest. Four foam-modified Hellcats launch for night intercept.

The pilots: Lieutenant Commander Edward O’Hare, Lieutenant Alex Veratzu, Ensign Warren Scone, and Ensign John Ballentine. O’Hare leads the formation through pitch black sky. They’re flying without lights, guided only by radar vectors from the Essex. The Japanese bombers are approaching at wave-top level, trying to avoid radar detection.

At 0247 hours, O’Hare spots the first Betty—a dark shape against darker water. He dives, opens fire at 300 yards. His tracers walk across the bomber’s fuselage. The Betty explodes, cartwheels into the ocean. Veratzu gets the second bomber. Scone gets the third. The night sky erupts with tracers and explosions.

The Japanese formation breaks apart, but O’Hare’s Hellcat takes damage. A Betty’s tail gunner scores hits on his port wing and fuel tank. Fuel streams from the punctured tank. The self-sealing lining does its job. The leak slows then stops. But O’Hare has lost fifty gallons. He’s running on fumes.

He heads back to the Essex. The carrier is pitching in heavy seas. O’Hare makes his approach, fighting crosswinds and low fuel. His wheels slam down. His tail hook catches the wire. The violent deceleration sends a shockwave through his half-empty fuel tanks. Before Sweat’s modification, O’Hare would have died instantly. His tanks would have exploded just like Lieutenant Anderson, just like Lieutenant Edwards. Instead, O’Hare walks away without a scratch.

The foam absorbed the shock. No vacuum formed. No rubber tore. No spark ignited. The combat results speak for themselves. In December 1943, night fighter-equipped carrier groups shoot down forty-seven Japanese aircraft with zero losses to fuel tank explosions. In January 1944, that number rises to sixty-three Japanese aircraft destroyed.

The Japanese notice. Captured documents reveal their confusion. Their intelligence reports describe American night fighters as invulnerable to combat damage and capable of sustained operations without mechanical failure. Japanese pilots begin avoiding night attacks on carrier groups entirely. The strategic impact is enormous.

Without the threat of night torpedo attacks, American carrier groups can operate more aggressively. They can close to within striking range of Japanese-held islands. They can maintain position during multi-day operations without retreating to safe waters after sunset. The kill ratios tell the story. Before foam-lined tanks, 19 to 1 in favor of American pilots during day operations, but night operations suspended due to explosion risk.

After foam-lined tanks, 23 to 1 during day operations, 31 to 1 during night operations. Japanese losses skyrocket. American losses plummet. By February 1944, the modification is standard on all Navy carrier aircraft—not just Hellcats, but Corsairs, Avengers, and Helldivers too. The foam lining technique is adapted for bomber fuel tanks, then for transport aircraft.

A German Luftwaffe intelligence report captured after the war describes the American innovation. “The enemy has developed a fuel tank system that renders their aircraft nearly immune to explosion during carrier operations. Our own attempts to replicate this system have failed. The American technical superiority and aviation safety measures represents a significant strategic disadvantage for our forces.”

In March 1944, Lieutenant Alex Veratzu, one of the pilots from that first night combat mission, tracks down Sweat in the Essex maintenance bay. Veratzu has just become an ace with nineteen confirmed kills. “I heard you’re the guy who fixed the fuel tanks,” Veratzu says. Sweat nods. “I took damage last week. Fuel tank hit. Made it back to the carrier on fumes. Slammed down hard on the deck. Walked away clean.”

Veratzu extends his hand. “Because of you, I’m alive. Because of you, a lot of guys are alive.” Sweat shakes his hand. He doesn’t know what to say. “How many pilots do you think you’ve saved?” Veratzu asks. Sweat has never calculated it. He was just trying to fix a problem.

The story of James Sweat reminds us that innovation often comes from unexpected places—from people who see problems differently because they’re not constrained by conventional thinking. If you want to hear more stories like this—stories about ordinary people who changed the course of history—please like this video and share it with someone who appreciates real heroes. Your support helps us continue bringing these forgotten stories to light.

Between November 1943 and August 1945, foam-lined fuel tanks prevented an estimated 394 fuel tank explosions in carrier aircraft. That’s 394 pilots who came home alive. 394 families who weren’t notified of their son’s death. 394 men who went on to fly more missions, shoot down more enemy aircraft, support more ground operations.

The Navy produced 12,275 F6F Hellcats during World War II. Every single one built after December 1943 had foam-lined fuel tanks based on Sweat’s design. The modification was also implemented in 10,049 F4U Corsairs, 9,839 TBF Avengers, and 7,040 SB2C Helldivers—total aircraft protected: 39,973.

But James Sweat never received public recognition during the war. The Navy classified the foam lining technique as confidential, fearing that if the Japanese understood the system, they might develop countermeasures. Sweat’s name appears nowhere in official histories published before 1990. He was promoted to chief petty officer in January 1944. He served on the Essex until the war ended, maintaining aircraft, training new mechanics, and quietly implementing improvements that saved lives.

When other sailors asked him about his role in the fuel tank solution, he deflected credit. “A lot of people figured it out,” he’d say. “I just got lucky.” After the war, Sweat returned to Terre Haute. He opened a small auto repair shop. He married his high school sweetheart, Mary Catherine Sullivan. They raised four children.

He never talked about his Navy service. His children didn’t know about his role in saving hundreds of pilots until a Navy historian tracked him down in 1991. The foam-lined fuel tank principle Sweat pioneered is still used today. Modern aircraft, military and civilian, use foam baffles in fuel tanks to prevent explosion during crashes. The Federal Aviation Administration mandates foam-based explosion suppression systems in commercial aircraft fuel tanks.

Formula 1 race cars use similar technology. Every time you board an airliner, you’re protected by a safety system that traces its lineage back to a 24-year-old mechanic who refused to accept that good men had to die. In 1993, the Navy awarded Sweat the Legion of Merit—forty-eight years late. The citation reads: “For exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements whose innovation in fuel system safety directly resulted in the preservation of hundreds of lives and contributed significantly to the success of naval aviation operations in the Pacific theater.”

Sweat attended the ceremony at the Pentagon. He was seventy-four years old. When reporters asked him how it felt to finally receive recognition, he said, “I was just doing my job. The real heroes are the pilots who flew those missions. I just made sure they could come home.” James Sweat died in 2009 at age ninety. His obituary in the Terre Haute Tribune Star mentioned his Navy service in the final paragraph. Most readers had no idea the quiet mechanic who’d fixed their cars for fifty years had saved hundreds of lives.

The lesson of James Sweat’s story isn’t about genius or credentials or formal education. It’s about seeing problems clearly, having the courage to act, and understanding that sometimes the most important innovations come from people who aren’t supposed to have the answers, but who refuse to accept that the answers don’t exist. Sometimes the person who changes everything is the person nobody expected. Sometimes the solution is simple, and sometimes breaking the rules is the only way to save lives.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load