Dr. Elena Vasquez had spent two decades coaxing secrets from faded photographs, but nothing in her career had prepared her for the morning the Boston Historical Society delivered the Thornton family portrait. It was August in Cambridge, the air heavy with the scent of rain on brick, and Elena sat in her sunlit studio, the photograph spread before her like a puzzle waiting to be solved.

The image, dated 1901, captured the wealthy Thornton family of Beacon Hill in their prime. Richard Thornton, stoic and proud, stood at the center, his wife Catherine a step behind, their three daughters in white lace, and a young boy—James—nestled between the adults. The garden was immaculate, the brownstone mansion rising behind them in stately confidence. It was, at first glance, a flawless snapshot of Bostonian prosperity.

Elena’s task was restoration: scanning the damaged print at the highest possible resolution, she set about brightening the faded whites, sharpening the blurred faces, and erasing the brown stains time had left behind. It was methodical, almost meditative work—until, deep in the shadow beneath an ancient oak at the edge of the frame, she saw something that made her heart stutter.

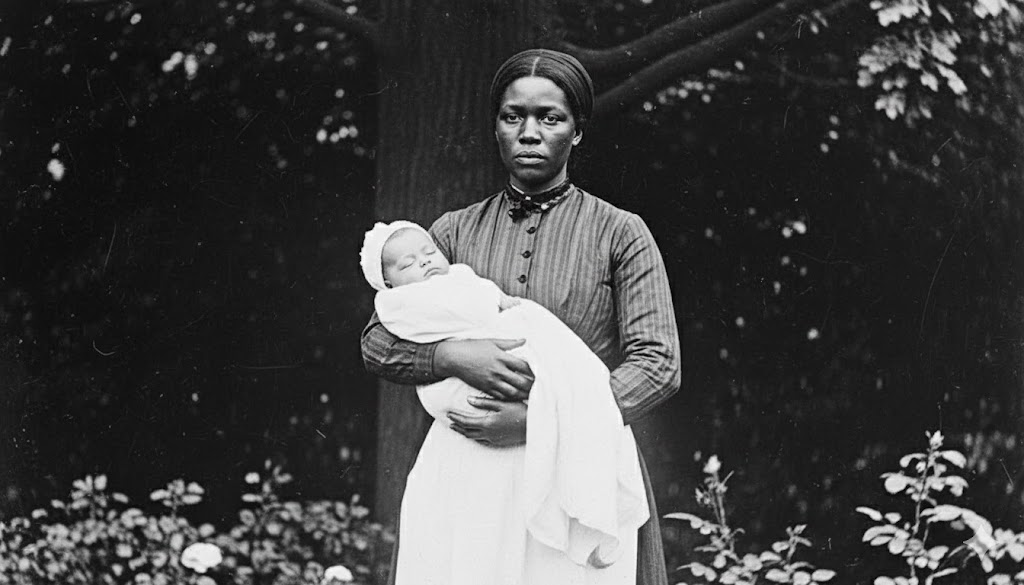

A figure. At first, it seemed a trick of the light, a garden ornament or a smudge. But as Elena magnified and enhanced the shadows, the figure resolved into a woman—black, dressed in the plain clothes of a domestic servant, half-concealed behind the tree. She was holding an infant, swaddled in white, her posture deliberate, her face etched with an emotion Elena could not name.

It was not unusual for servants to appear in the periphery of family portraits from that era, but there was something about this woman’s presence—intentional yet hidden, proud yet resigned—that unsettled Elena. The infant in her arms appeared light-skinned, and the woman’s gaze, even in shadow, radiated a fierce, quiet strength.

Elena’s mind raced. She turned to the documentation that had come with the photograph: Richard, Catherine, their daughters Margaret, Elizabeth, and Anne, and their “orphaned nephew” James—all named, all accounted for. But the woman in the shadows was unnamed, unmentioned. The historical society’s notes were silent on her existence.

That evening, as rain spattered the windows, Elena pored over census records and household ledgers. She found, in a ledger from 1901, a name: Clara Washington, cook and housemaid, $8 per month, room included. The payments stopped abruptly in 1902, with a single word in the margin: dismissed.

The next morning, Elena called Dr. Patricia Chen, the historical society’s curator. “Patricia, there’s something in the photograph,” she began, describing the hidden woman and the infant. Patricia listened, intrigued. “The Thorntons donated the collection six months ago,” she said. “They claimed it was just old family records. But if you think there’s a story, I’ll help you look.”

Together, they sifted through the family’s papers. In a letter from Catherine Thornton to her sister, dated March 1901, Elena found a cryptic passage: “We have taken in Richard’s nephew James, following the tragic loss of his parents. The boy is adjusting well, though the circumstances have been complicated by unfortunate rumors. We are making household adjustments to ensure propriety.”

Elena’s instincts sharpened. She and Patricia tracked down James’s birth certificate: born February 1896 in Boston, to Richard’s brother—supposedly. But the dates didn’t match. James’s parents had died in 1898, not 1896. Why, then, was James’s birth recorded in Boston, when his parents lived in New York? And why did his birth certificate bear the notation: Amended record?

Elena’s hunch grew stronger. She dove into hospital records from Boston Lying-In Hospital. There, in February 1896, was an entry: Clara Washington, negro, age 21, delivered of a male infant. Father: unknown. The attending physician’s note read: “Patient employed by R. Thornton family. Infant to remain with mother and Thornton household per arrangement. Fee paid by R. Thornton.”

The pieces began to fit. Clara, a young black woman from Virginia, had come north after the Civil War, found work with the Thorntons, and in 1896 had given birth to a son—James—fathered by Richard Thornton. The family had paid her hospital bills, then rewritten the story, recasting James as an orphaned nephew.

But what of the infant in the 1901 photograph? James would have been five by then, not a baby. Elena scrutinized the photograph, comparing the infant’s features to those of the boy standing with the Thorntons. The baby in Clara’s arms was a newborn, no more than a few months old. There were two children in the photograph: James, the boy taken in as a nephew, and a baby girl, Clara’s daughter.

They searched birth records from 1901 and found it: a female infant, born to Clara Washington in March 1901, hospital fees again paid by Richard Thornton. In September, the records of the Boston Home for Colored Children noted the intake of a six-month-old girl, surrendered by her mother, adoption pending. The adoption was finalized a month later, the records sealed, a substantial donation made by an anonymous benefactor.

Elena’s heart ached. The photograph had captured Clara’s last moment as a mother to both her children—James, already claimed by the Thorntons, and her infant daughter, soon to be adopted away. The family had allowed Clara to stand in the shadows, holding her baby, as a final act of acknowledgment before erasing her from their lives.

But someone had wanted the truth preserved. The photograph survived.

Elena’s search for Clara’s fate led to dead ends until Patricia found a letter in the archives of Boston’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. Dated 1902, it was from Clara to her pastor: “I have raised my son James with love, though his father demands secrecy. Now his wife insists I be dismissed, and James will remain with them. I am unfit, she says. I have no legal standing. If I fight, they will destroy me, or harm James. If I accept, I lose my child, but he may have a better life. I pray for guidance.”

Elena wept as she read Clara’s words. The pain, the impossible choice, the love that endured even as her children were taken from her. She wondered: Had James ever learned the truth? Had Clara’s daughter ever known her origins?

Tracing James through census records, Elena saw him grow into adulthood: a Harvard graduate, a successful attorney, married, with children of his own. The 1930 census listed his race as white, but a faint, amended notation read: mulatto. Had someone questioned his identity? Had rumors of his parentage lingered?

In 1935, James made headlines defending a black family forcibly evicted from their home. Over the years, he became a prominent civil rights attorney, fighting segregation and discrimination in Boston. In a 1954 speech, he spoke of “debts owed to those whose sacrifices go unrecognized,” and the need to fight for a world where “love and family are not constrained by the artificial boundaries of race.”

Elena’s investigation led her to James’s grandson, Michael Thornton, a retired professor of African-American history. When Elena called, Michael listened in stunned silence, then invited her to his home. There, surrounded by boxes of family papers, Michael handed Elena a letter written by his grandfather in 1974:

“I am not who the world believes me to be. I am the son of Richard Thornton and a black woman named Clara Washington. I learned the truth at age thirty, when Clara found me and showed me a photograph of herself holding me as an infant. I spent her last years with her, learning her story, understanding the choices she made. I dedicated my life to fighting the injustices she endured. Clara Washington was your great-grandmother. Honor her memory.”

Michael had been searching for his great-aunt, Clara’s daughter, for years. He had found only sealed records and dead ends. Elena suggested publicizing the photograph, hoping someone might recognize the story.

The photograph’s secret, once revealed, made national headlines. Newspapers and television programs ran features on the hidden history of the Thornton family. Three days after the story broke, Michael received an email from Diane Roberts in Harlem. Her grandmother, adopted from a Boston orphanage in 1901, had always wondered about her origins. She had a cropped photograph showing a black woman in a garden, holding a baby. When Diane sent the photograph to Michael, he recognized it immediately: it was Clara, holding her infant daughter.

Diane traveled to Boston, where she and Michael, both descendants of Clara, met for the first time. At the historical society, Elena showed Diane the full photograph. Diane wept as she gazed at her great-grandmother’s face. “She loved me,” she whispered. “Even knowing she would have to give me up, she loved me.”

Michael and Diane’s families, separated for over a century by race, adoption, and secrecy, were reunited. They founded the Clara Washington Foundation, dedicated to researching cases of forced family separation and supporting genealogical research for African-Americans seeking lost relatives. The Boston Historical Society created a permanent exhibit about Clara, James, and the photograph—a testament to hidden histories and the resilience of black mothers.

The exhibit did not shy away from complexity. Richard Thornton, who had fathered two children with Clara, was neither lionized nor demonized. Clara’s own words, preserved in her letters, spoke honestly of the imbalance of power: “What freedom does a servant have when her employer demands her company? I cared for him. But care within such an imbalance cannot be called love—not truly.”

As the story spread, more families came forward with photographs, letters, and whispered stories of black ancestors hidden in white family histories. The photograph of Clara became iconic, featured in textbooks, museum exhibits, and art inspired by her dignity and loss.

But the most profound legacy was personal. Michael, Diane, and later Linda—a third descendant whose grandmother had also been adopted from the Boston Home for Colored Children—stood together at Clara’s grave in Roxbury. They commissioned a new headstone: “Clara Washington, 1875–1935. Beloved Mother. Her strength lives on in her descendants.”

At the dedication ceremony, Elena spoke of her journey: “Clara Washington was rendered invisible by a society that denied black women’s humanity. But she found a way to be seen. She stood in that garden, holding her baby, and insisted on being photographed. That act of quiet resistance is what allowed her story to survive.”

The photograph, once a simple family portrait, had become a key to unlocking a hidden history—a story of love, loss, injustice, and reunion. Michael’s children, who had grown up identifying as white, grappled with the revelation of their black ancestry. Diane’s family, who had always identified as black, welcomed their newly discovered relatives, even as they mourned the injustices that had separated them.

The Clara Washington Foundation helped other families trace lost ancestors, funded DNA testing, and advocated for opening sealed adoption records. On the 125th anniversary of the photograph, Clara’s descendants gathered in the garden where the image had been taken, now a public park. They planted a tree in Clara’s honor and installed a plaque telling her story.

Elena reflected on the journey: “When I first saw that shadow in the garden, I didn’t know I was looking at Clara Washington. I didn’t know I was about to uncover a story of love and loss, exploitation and resistance. I simply saw something hidden. That’s what historians do—we bring light to the shadows.”

As the sun set over the garden, Clara’s family—black and white, united after generations of separation—stood together in the place where she had insisted on being seen. Clara Washington, once hidden in the shadows, was finally, fully, undeniably seen. Her legacy, carried by her descendants and the countless people inspired by her story, would ensure she was never forgotten.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load