The courthouse records were thought to be lost forever. Everyone believed the fire of 1865 had destroyed the entire building, turning decades of Virginia’s shame into ash and smoke. But in the basement of the old Henrio County Clerk’s Office, behind a wall that collapsed during renovations in 1973, workers discovered something that should not have survived: an iron strongbox, sealed and hidden.

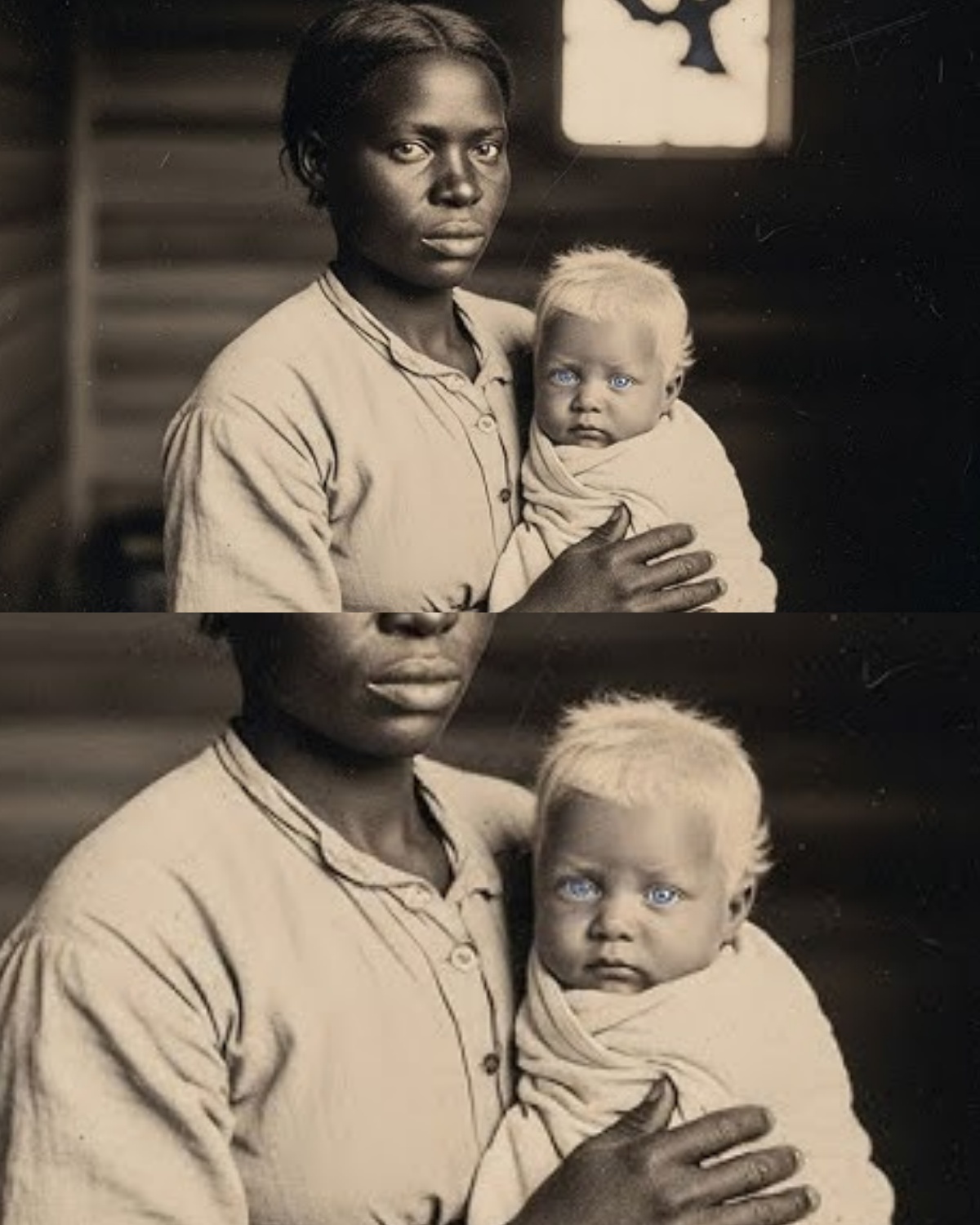

Inside were papers that had been deliberately preserved, not official records but personal letters, diary entries, testimonies never meant to be heard, and photographs—daguerreotypes from the early 1840s. These images showed 23 children over five years, all with the same emerald green eyes and pale blonde hair. Every one of them was born to enslaved women in Henrio and Chesterfield counties. All had the same father.

The photographs were haunting. Small faces stared at the camera with expressions far older than their years, children dressed in the rough clothing of the slave quarters but with features that seemed lifted from a European portrait gallery. The eyes were what struck you first—not blue, not gray, but emerald green, bright and unmistakable. Next to each photograph, in careful script, were names, dates, plantations, and a single word repeated again and again: “His.”

The woman who found these documents brought them to a historian at the University of Virginia. The historian spent six months verifying the evidence, cross-referencing names with plantation records, birth registries, and land deeds. Everything checked out. When she finally published her findings in a small academic journal, the response was silence—not controversy, not outrage, just silence.

What do you do with evidence of something so systematic, so deliberate, that even 130 years later, people would rather pretend it never happened? But it did happen. In the tobacco counties of central Virginia between 1839 and 1844, 23 children were born with emerald eyes and blonde hair—children who looked nothing like their mothers. Their very existence was evidence of something that had no name under Virginia law, because in 1840, enslaved women were not considered people. They were property. And you cannot commit a crime against property.

Before we go further, I want to invite you to subscribe to The Sealed Room. Hit the notification bell—these stories matter. Drop a comment below letting me know where you’re watching from, your state, your city. Now, let’s uncover what really happened in those Virginia counties between 1839 and 1844.

The story doesn’t begin with an overseer noticing a pattern or with whispers traveling between plantations. It begins with a woman named Ruth, 31 years old, standing in a cabin on Fair View Plantation in April 1839, holding a newborn baby and knowing her life had changed forever. Not because of what the baby looked like—though that was impossible to ignore—but because she knew what had happened. She knew who the father was, and she knew there was nothing she could do about it.

Ruth had been born in Richmond and sold south to Fair View at age 19, separated from her mother and three sisters in a transaction that took less time than buying a horse. She spent 12 years at Fair View, learning the rhythms of tobacco cultivation, which overseers to avoid, and how to be useful enough to stay invisible enough to survive. She was paired with a man named Daniel when she was 23, a match arranged by the plantation owner to produce children who would become valuable property. Daniel was a good man—quiet, strong, working the fields from dawn until dusk.

They already had one daughter, Sarah, seven years old, who looked like her parents: dark skin, dark eyes, tightly curled hair. This second child should have looked the same. Ruth carried her for nine months, felt her grow and move, prepared herself for the pain and exhaustion of childbirth, for the strange joy of holding a new baby. But she was not prepared for what she saw.

The baby girl in her arms had skin so pale it looked like cream, hair blonde and fine, and eyes—those eyes—emerald green, bright as jewels, impossible. Ruth stared at her daughter and felt something crack open inside her chest. Not love, not yet—just recognition. This was evidence. This was proof. This child’s face was a confession written in flesh and bone.

The midwife, an older woman named Patience, said nothing. She cleaned the infant, cut the cord, wrapped her in cloth, and handed her to Ruth with an expression that said everything: I know, you know, we both know. And neither of us can speak it aloud.

Daniel came to the cabin an hour later, exhausted from working the far fields, not yet aware of the birth. He stopped three feet from Ruth, his eyes moving from the baby to Ruth’s face and back again. His mouth opened, closed, opened again. No words came out. “That’s not mine,” he finally managed, his voice flat and empty.

“She’s yours,” Ruth whispered. “She has to be. Look at her, Daniel. Look at her eyes. Look at her hair.” Daniel insisted, “I haven’t been with anyone else. You know that. You know I haven’t.” Ruth asked, “Then how do you explain this?” Daniel could not. The silence that followed was worse than any words.

Daniel left the cabin, did not return that night or the next. By the end of the week, he had requested reassignment to a different work crew, a different cabin, a different life that did not include Ruth or the impossible baby she had brought into the world.

Ruth named her daughter Grace. The name felt like both a prayer and a curse. Grace grew quickly—healthy, alert, beautiful in a way that made people stare. By three months, her emerald eyes were even more striking, her blonde hair thick and soft. She looked like a porcelain doll dropped into the slave quarters.

Other enslaved people at Fair View did not know what to make of Grace. Some avoided looking at her entirely. Others stared when Ruth wasn’t watching. A few older women approached Ruth privately, asking careful questions: “Has anyone bothered you? Has anyone come to your cabin at night?” Ruth’s answer was always the same: “No, I don’t know what happened. I can’t explain it.” But that was a lie.

Ruth knew exactly what had happened. She knew who Grace’s father was. She had known from the moment she saw those emerald eyes. She just could not say it aloud. Could not speak the name. Because naming the father meant acknowledging something so dangerous, so impossible to prove, so certain to bring punishment, that silence was her only protection.

The father was Jonathan Blackwell, 34 years old, the second son of the family that owned Fair View. Ruth remembered the night it happened in every detail. It was December, after the tobacco harvest, the fields dormant until spring. Ruth was called from the quarters to help clean the main house for a Christmas party.

She finished late, past midnight, and was heading back when Jonathan Blackwell appeared in the hallway. He had been drinking; she could smell whiskey and tobacco on him, and something sharp and wrong. He blocked her path, smiled, asked where she was going. Ruth kept her eyes down, murmured she was returning to the quarters, tried to step around him. He blocked her again, caught her arm—gently at first, then tighter.

What happened next lasted maybe ten minutes, maybe less. Time fractured and stretched in ways Ruth could not track. There was a room, a locked door, Jonathan’s voice low and calm, telling her not to fight, not to scream, that it would be easier if she did not resist. Ruth had learned long ago that resistance brought worse punishment, so she retreated somewhere in her mind, far away from her body, from the room, from what was being done to her.

When it was over, Jonathan straightened his clothes, told her she could go, warned her not to speak of it to anyone. Ruth returned to the quarters in the dark, her body moving on instinct while her mind stayed floating, disconnected. She climbed into bed beside Daniel, lay there until dawn, staring at the ceiling, feeling something inside her break that would never fully heal.

Three weeks later, she missed her monthly bleeding. By February, she knew she was pregnant. By March, she understood with cold certainty whose child she was carrying. And in April, when Grace was born with Jonathan Blackwell’s emerald green eyes staring up at her, Ruth’s worst fears were confirmed.

Now, holding her daughter and watching those impossible eyes track movement across the cabin, Ruth made a decision. She would raise this child. She would love her. She would protect her as much as any enslaved woman could protect her children. But she would never speak the truth aloud, never name the father, never give anyone the satisfaction of confirmation—because what good would it do?

Jonathan Blackwell was white, wealthy, protected by law and social standing. Ruth was property. Her testimony meant nothing. Her pain meant nothing. Her violation meant nothing. The system was working exactly as designed.

Grace was six months old when the second baby was born—different plantation, different mother, same impossible features. The plantation was called Riverside, eight miles east of Fair View along the James River. The mother was Hannah, 24 years old, who worked in the tobacco fields. The baby was a boy—blonde hair, emerald green eyes, pale skin that looked translucent in lamplight.

Hannah’s reaction was different from Ruth’s. She screamed when she saw her son, screamed until the midwife had to physically restrain her, hissing at her to be quiet before the overseer came running. Hannah’s partner, Jacob, took one look at the baby and walked out. He never came back.

Hannah refused to hold her son for three days, refused to feed him, refused to even look at him. Finally, another woman in the quarters forced Hannah to understand: “You either feed this baby or he dies. And if he dies, they’ll blame you. They’ll punish you. He’s your child now, whether you want him or not.” Hannah named him Thomas and kept him alive, but she never stopped hating him. She never stopped seeing his emerald eyes as evidence of something she could not speak about, could not process, could not survive if she let herself feel it fully.

News traveled slowly at first, plantation to plantation along the James River, carried by traders, by enslaved people with family connections across county lines, by the invisible network that existed beneath the surface of Virginia society. Two babies, different plantations, same impossible features. People started paying attention.

The third birth happened in January 1840 at Meadowbrook Plantation, twelve miles north of Richmond. The mother was Esther, 19 years old, assigned to the main house kitchen. The baby was a girl—emerald eyes, blonde hair so pale it looked white in the winter sun. Esther’s partner, Moses, disappeared the night the baby was born, just walked off the plantation. He was found three days later, half frozen, barely alive. He never spoke about why he ran, never acknowledged the baby. When they brought him back, whipped him for running, sent him back to work, he moved like a ghost—empty, hollowed out.

The fourth birth came in April 1840 at Cedar Hill Plantation, just across the county line into Chesterfield. The mother was Mary, 26 years old, respected for her practical wisdom. The baby was a boy—those same emerald eyes stared up from a face framed by blonde hair. Mary cared for him mechanically, fed him, changed him, kept him alive, but her face stayed blank, her eyes distant, like she had retreated somewhere inside herself where the world could not reach her.

By summer 1840, plantation owners across Henrio and Chesterfield counties became aware of the pattern—not because they were looking for it, but because the whispers had grown too loud to ignore. Four babies in just over a year. Four different plantations. Four enslaved women who all told the same story: they had been with no one but their recorded partners. They could not explain their children’s appearance. They had nothing more to say.

The plantation owners met privately, quietly, in drawing rooms and libraries over cigars and brandy, discussing the situation in careful language. The consensus was clear: this was embarrassing, potentially scandalous, but not criminal—not under Virginia law. Enslaved women were property. Their children were property. Whatever had produced these strange-looking children, it was not anyone’s legal concern.

But one man could not let it go. His name was William Carter, 52 years old, owner of Ashland Plantation. Carter was unusual among Virginia planters—educated, widely read, troubled by the moral implications of slavery. He tried to run his plantation humanely, did not whip his enslaved people unless absolutely necessary, provided adequate food and shelter, did not separate families when he could avoid it. This made him neither a hero nor a villain, just a man trying to reconcile an unconscionable system with his own sense of decency, failing at both.

Carter heard about the births through his overseer, Thomas Reed, who kept detailed records of everything that happened on Ashland. Reed mentioned the pattern casually one evening in May 1840, discussing plantation gossip as they reviewed the season’s accounts. “I heard about another one of those strange births,” Reed said, running his finger down a column of numbers. “Over at Cedar Hill this time. Same as the others. Blonde hair, green eyes. Mother swears she’s been with no one but her man. How many does that make now?”

Carter, only half paying attention, asked, “Four that I know of. Maybe more that haven’t been talked about.” Carter looked up from the ledgers. “Four? In how long?” “Just over a year. All within about 15 miles of here.” “That’s not coincidence.” “No, sir. I don’t believe it is.”

Carter set down his pen and gave Reed his full attention. “Tell me everything you’ve heard.” Reed laid out the dates, the plantations, the mothers’ names, the identical features of the children, the insistence from every mother that they had been with no one but their recorded partners. The pattern was undeniable.

“Someone is fathering these children,” Carter said slowly. “Someone with access to multiple plantations, someone who moves between properties without drawing attention.” Reed had been tracking visitors—traders, overseers, doctors, clergy—anyone who might have opportunity. One name appeared more often than chance would suggest: Jonathan Blackwell, from Fair View.

The Blackwell family was well known in Henrio County, old money, old Virginia, influential since colonial times. The current patriarch, Edmund Blackwell, was respected and powerful. His oldest son, Charles, was being groomed to take over the plantation. His second son, Jonathan, was a disappointment—unmarried, known for drinking too much, accomplishing too little.

Jonathan lived at Fair View but had no real responsibilities, spending his time riding between neighboring plantations, visiting friends, attending social gatherings. Reed’s notebook showed Jonathan attended a dinner party at Riverside three months before Hannah’s baby was born, visited Meadowbrook two months before Esther’s baby, stopped at Cedar Hill during a hunting trip three months before Mary’s baby. And the first birth was at Fair View—his own plantation.

Carter sat back, understanding the implications. If Jonathan Blackwell was responsible, if he was deliberately fathering children with enslaved women across multiple plantations, the scandal would be enormous. Not because such things did not happen—they happened constantly—but because of the pattern, the deliberateness, the emerald eyes that marked each child as unmistakably his.

“What are you suggesting we do?” Reed asked. Carter did not answer immediately. He understood the delicate position he was in. Accusing Jonathan Blackwell without absolute proof would be social suicide, but doing nothing felt like complicity. “I need to think about this,” Carter finally said. “Say nothing to anyone. Keep tracking the pattern if there are more births. But quietly. Very quietly.”

Over the following months, Carter wrestled with what to do. He consulted law books, looking for any statute that might apply. But Virginia law in 1840 was clear: enslaved people were property, had no legal standing, could not bring charges, could not testify against white people in court. Children born to enslaved women belonged to the women’s owners, regardless of paternity. There was no crime here—not legally. But morally, Carter could not shake the feeling that something profoundly wrong was happening.

The fifth birth came in August 1840 at Willow Creek Plantation, ten miles west of Richmond. The mother was Abigail, 22 years old. The baby was a girl with emerald eyes and blonde hair. Abigail held her daughter and wept silently, her body shaking. Her partner, Samuel, stared at the baby for a long time, then simply said, “I can’t. I can’t do this.” He left the cabin and never returned as a family. They worked the same fields, passed each other daily, but Samuel never spoke to Abigail again, never acknowledged the child.

Reed reported the birth to Carter. Jonathan Blackwell had attended a barbecue at Willow Creek four months earlier. The sixth birth came in November 1840 at Greenwood Plantation. The mother was Rebecca, 28 years old; the baby was a boy with the same impossible emerald eyes. Rebecca’s partner, Benjamin, became violent when he saw the child, smashing the cabin’s only chair, punching a hole in the wall, screaming questions that had no answers. Rebecca could not explain what had happened without speaking words that would get her killed.

The pattern was accelerating—six babies in less than two years. And Jonathan Blackwell’s name appeared in the background of every single situation. Always visiting, always present at the right plantation at the right time, never obviously, never suspiciously—just there.

Carter decided he needed to speak with the mothers directly, not to interrogate them, but to offer them something no one else had: the opportunity to be heard. He started with Ruth at Fair View, since she was the first mother and her daughter Grace was now 18 months old, walking and talking, those emerald eyes bright and aware.

Carter arranged to visit Fair View, using a business discussion as a pretext, and asked permission to inspect the quarters, claiming he was considering changes at his own plantation. Edmund Blackwell agreed. Carter found Ruth hanging laundry outside her cabin, Grace playing nearby, her blonde hair catching the afternoon sun like a beacon.

Ruth saw Carter approaching and went still, her hands frozen on the wet sheet. Every enslaved person knew that when a white man approached with purpose, it rarely meant anything good. “Ruth,” Carter said gently, “I’d like to speak with you, if you’re willing.” “Yes, sir,” Ruth replied, her voice neutral.

“About your daughter.” Ruth’s jaw tightened. “Grace is healthy, sir. No trouble.” “I’m not here about trouble. I want to understand what happened—who her father is.” The silence stretched between them. Grace babbled, oblivious to the tension. “Daniel is her father, sir. That’s what the records show.”

“Ruth, I know that’s not true, and I think you know who the real father is.” Ruth turned to face him directly, her eyes hard, guarded, filled with something Carter could not quite name—grief, maybe, or rage buried so deep it had turned to stone. “With respect, sir, what difference does it make who I think the father is? I’m property. My daughter is property. Property doesn’t get to name fathers. Property doesn’t get justice. Property just survives.”

“I want to help.” Ruth laughed, a sharp, bitter sound. “Help how, sir? Will you give me my freedom? Make my daughter free? Arrest a white man based on the testimony of a slave woman? Unless you can do one of those things, your help is just words.”

Carter felt the truth of her words like a physical blow. She was right. He had no real power to help her, no legal avenue, no way to deliver justice even if she told him everything. “But I can document what happened,” Carter said quietly. “I can create a record, so that someday, when things change, when the law changes, there’s evidence, there’s truth preserved.”

“Truth doesn’t matter without power, sir.” “Maybe not now, but someday it might.” Ruth stared at him, evaluating whether this white man was sincere or just another kind of danger. Finally, she spoke, her voice low and controlled. “His name is Jonathan Blackwell. He came to me in December 1838. I was working in the main house. He cornered me, locked a door, told me not to fight. I didn’t fight because I wanted to live. I didn’t scream because I wanted to wake up the next morning. I didn’t tell anyone because who would believe me? Who would care? Nine months later, Grace was born. Every time I look at her eyes, I see his eyes. Every time I hear her laugh, I remember that night. Every time I hold her, I feel him still touching me. That’s the truth, sir. You want to write it down? Write it down. But it won’t change anything. It won’t punish him. It won’t protect the next woman. It won’t make my daughter any less a slave. It won’t make me any less property.”

Carter left Fair View shaken. Intellectually, he had known the system was cruel, but hearing Ruth speak so plainly about her violation, about her absolute powerlessness, made it real in a way abstract knowledge never could.

He visited the other mothers in the following weeks, traveling to Riverside, Meadowbrook, Cedar Hill, Willow Creek, and Greenwood. Each time, he used some pretext to speak privately with the women. Each time, the story was the same: Jonathan Blackwell, access to the main house or isolated locations, a locked room or a threat, or simply the understanding that resistance was pointless. Silence. Nine months later, a baby with emerald eyes.

Hannah at Riverside told him through tears, “He said if I screamed, he’d have me whipped. So I didn’t scream.” Esther at Meadowbrook stared at the ground, “He smelled like whiskey and tobacco. I remember that smell. I still smell it sometimes and I can’t breathe.” Mary at Cedar Hill spoke in a flat, dead voice, “I stopped fighting after the first minute. What’s the point? He was going to do what he wanted. I just wanted it to be over.” Abigail at Willow Creek could not speak at all. She just nodded when Carter said Jonathan’s name, closed her eyes, stood trembling. Rebecca at Greenwood told him with anger, “You want to know who the father is? Look at my son’s eyes. They’re his eyes. That’s all the proof you need. That’s all the proof that matters. And it means nothing because we’re property and property can’t be raped.”

Carter documented everything—dates, names, testimonies. He cross-referenced Jonathan Blackwell’s movements, confirming his presence at each plantation during the crucial periods. The evidence was overwhelming, undeniable, and completely useless under Virginia law.

By spring 1841, there were eight children. The pattern was so clear that even plantation owners who had dismissed it as coincidence had to acknowledge something was happening. But acknowledging it and doing something about it were different matters.

Carter tried to approach Edmund Blackwell directly. He requested a meeting, sat in Edmund’s study surrounded by portraits of Blackwell ancestors, and explained what his son had done. Edmund listened in stony silence. When Carter finished, Edmund stood, walked to the window, his back to Carter. “My son is not a rapist,” Edmund said quietly. “Edmund, the evidence.” “There is no evidence. There are accusations from women who have no legal standing. There are children who happen to have light features. That proves nothing.” “Eight children, Edmund. Eight. All with the same distinctive features, all born to mothers who had contact with Jonathan at the precise time for conception.” “Coincidence. Or perhaps these women were with white men from other plantations and are lying about the fathers.” “Why would they lie?” “To cause trouble. To create scandal. Who knows why slaves do what they do?”

Carter felt frustration rising. “These women aren’t lying. They’re terrified. They’re traumatized. They’re trying to survive in a system that gives them no protection.” “This conversation is over,” Edmund said, turning back to face Carter, his face hard and closed. “My son is innocent. These accusations are slander. If you repeat them publicly, I will destroy you. I will ruin your reputation, your business, your standing in this county. Do you understand?” “Yes.” Carter stood, defeated. He left Fair View knowing the battle was lost before it had begun. The Blackwell family had too much power, too much influence, and the law itself was on their side.

Because in Virginia in 1841, enslaved women were not people. They were property. And you cannot commit a crime against property.

The births continued through 1841 and 1842—two more in summer, three in fall, another in winter, four in spring. The children grew. Grace at Fair View was now three, speaking in full sentences, asking why she looked different from the other children in the quarters. Thomas at Riverside was bright and curious, reaching for his mother, who still flinched at his emerald eyes. The newer babies were still infants, but already their features set them apart, marking them as evidence of something no one wanted to acknowledge.

The women began meeting in secret. Not all, but some—those who could slip away unnoticed, who had family connections or work assignments bringing them together. They met at a church on the outskirts of Richmond, Mount Zion, where free black people and enslaved people with permission gathered on Sunday afternoons.

The minister, Reverend Isaiah Grant, born free in Philadelphia, had come to Virginia to preach despite the risks. He noticed the women—the way they sat together, the way they looked at each other with recognition deeper than fellowship, the way they held their strange-looking children close, protective, ashamed, defiant all at once. He had heard the rumors, of course: babies with emerald eyes, a pattern that suggested something deliberate, something monstrous.

One Sunday in June 1842, after service ended, Reverend Grant approached Ruth outside the church, Grace playing nearby. “Sister Ruth,” he said gently, “may I speak with you?” Ruth looked up, weary. “Yes, Reverend.” “I’ve been watching you and some of the other women—the ones with children like yours, children who look like they’ve been touched by something impossible.” Ruth’s face went blank. “I don’t know what you mean, Reverend.” “I think you do. And I think you’re carrying something too heavy to carry alone.”

The words broke something in Ruth. She began to cry—not the silent tears she’d learned to hide, but deep, wrenching sobs. Reverend Grant sat beside her, said nothing, just waited. Sometimes the greatest kindness was simply bearing witness.

When Ruth could speak again, she told him everything—Jonathan Blackwell, the locked room, the violation, Grace’s impossible eyes, the other women with the same story, the same nightmare, the same children marked by the same man. She told him about William Carter’s investigation, about Edmund Blackwell’s threats, about the impossibility of justice under Virginia law.

Reverend Grant listened to it all. When Ruth finished, he was quiet for a long time, his face grave. “How many women?” he finally asked. “That I know of—nine. But I think there might be more who haven’t spoken, who are too afraid.” “And the children?” “Fourteen. The oldest is Grace. The youngest was born last month.”

Reverend Grant stood and paced, thinking. Ruth watched him, hoping for wisdom, comfort, some way forward that didn’t exist. “The law won’t protect you,” Reverend Grant said. “Virginia law sees you as property. Your testimony means nothing. Your pain means nothing. Your children are property that belongs to your owners. There’s no legal recourse.” “I know,” Ruth said, “but there are other kinds of power besides the law.”

“What do you mean?” Ruth asked. “Virginia’s planters care deeply about reputation, about social standing, about how they’re seen by their peers. A legal case might be impossible. But public scandal, public shame—that’s something they fear.” “You want us to speak publicly?” Ruth was incredulous. “They’d kill us or sell us away from our children. Or worse.” “Not you. You can’t speak. Your voices don’t carry in this world, but mine does. I’m free. I have standing. I can write. I can publish. I can tell your story in ways that reach people who matter.” “And you think that would change anything?” “I don’t know. But I know that silence protects the powerful. And I know that sometimes the only weapon the powerless have is truth spoken loudly enough that people can’t ignore it.”

Ruth considered this. The idea was terrifying, dangerous. It could bring punishment down on her, on the other women, on their children. But it could also do something they had never been able to do—make noise, force people to see, refuse to let this be buried in silence. “Let me talk to the others,” Ruth said. “See if they’re willing.”

Over the following weeks, Ruth spoke with the other mothers she knew—Hannah at Riverside, Esther at Meadowbrook, Mary at Cedar Hill, Abigail at Willow Creek, Rebecca at Greenwood, and three others: Sarah, Catherine, and Elizabeth from plantations Ruth had only recently learned about. Twelve mothers of children with emerald eyes.

The conversations were difficult. Some women were too afraid—the risk of speaking, even through Reverend Grant’s voice, felt too great. But others were angry—so angry they would burn everything down if it meant Jonathan Blackwell faced consequences. In the end, seven agreed to share their stories—seven testimonies Reverend Grant could weave into a document exposing what had happened.

Reverend Grant worked through the summer of 1842, interviewing each woman privately, recording their testimonies with precision. He documented dates, locations, circumstances, noted the distinctive emerald eyes, created a timeline showing the undeniable pattern. He wrote an essay, powerful and uncompromising, laying out the evidence and demanding accountability. He titled it “A System That Protects Monsters: The Case of Jonathan Blackwell and the Violation of Enslaved Women in Henrio County, Virginia.”

The essay was fifteen pages long. It began with a philosophical argument about law and justice, questioning whether a system that defined human beings as property could ever deliver moral justice. Then it detailed the testimonies of the seven women, presenting their stories in their own words as much as possible. Finally, it concluded with a direct challenge to Virginia’s planters: “If you claim to be Christian men, if you claim to value honor and decency, if you claim that slavery is benevolent, then explain Jonathan Blackwell. Explain fourteen children with emerald eyes. Explain a pattern so deliberate it can only be called systematic. Explain your silence.”

Reverend Grant knew the essay was dangerous. Publishing it could get him arrested, beaten, killed. Free black men who challenged the system did not survive long in Virginia. But he also knew that silence was complicity, and he would rather die speaking truth than live as an accomplice to horror.

He sent the essay to three publications: an abolitionist newspaper in Philadelphia, a religious journal in Boston, and a small Richmond paper known for controversial pieces. The Philadelphia paper printed it in September 1842. The Boston journal printed it in October. The Richmond paper refused, but copies of the other publications made their way back to Virginia, passed from hand to hand, read in secret, discussed in whispers.

The reaction was explosive. Abolitionists in the North seized on the story as evidence of slavery’s inherent evil—the systematic violation of enslaved women, the creation of children as evidence, the absolute legal immunity of the perpetrator. It confirmed everything they had argued about the moral bankruptcy of the institution.

In Virginia, the response was fury—not at Jonathan Blackwell, but at Reverend Grant. “How dare a free black man make such accusations? How dare he slander a prominent Virginia family? How dare he spread lies designed to damage the South’s reputation?” The essay was denounced from pulpits, in newspapers, in the Virginia General Assembly. Reverend Grant was called a liar, an agitator, a tool of Northern abolitionists seeking to destroy Southern society.

Edmund Blackwell demanded Reverend Grant’s arrest. He hired lawyers, filed complaints, used every legal tool available. But Reverend Grant had not broken any Virginia law. He had published in Northern papers, beyond Virginia’s jurisdiction. He had stated facts, presented testimonies, asked questions. Nothing he had written was technically criminal, however inflammatory.

But legal immunity did not mean safety. In November 1842, Reverend Grant’s church was burned to the ground. Mount Zion went up in flames one night, the building reduced to ash by morning. No one was caught. No one was charged. Everyone understood it was a warning.

Reverend Grant fled Virginia a week later, barely ahead of a mob that would have killed him. He made it to Philadelphia, continued his ministry, kept writing about the Blackwell case and others like it. But his departure left the women in Virginia without their voice, without their advocate, alone again with their emerald-eyed children and unspeakable knowledge.

Jonathan Blackwell’s response to the essay was silence. He did not deny the accusations, did not defend himself, did not speak publicly at all. He simply continued his life as before—riding between plantations, attending social gatherings, drinking too much, accomplishing too little. The only change was subtle: he stopped visiting plantations outside Fair View, stopped attending dinner parties and barbecues at neighboring properties. He stayed home, within his family’s protection, surrounded by people who would never question him.

Because that is what the system did—it protected men like Jonathan Blackwell. It gave them absolute power over people defined as property. It made their crimes invisible, their violations legal, their victims silent. And when someone tried to speak truth, when someone tried to pierce that silence, the system crushed them, burned their churches, drove them into exile, preserved the power structure at any cost.

The births continued through 1843—three more children, all with emerald eyes, all born to women at Fair View, Jonathan’s own plantation, where he no longer needed to travel elsewhere. The pattern shifted but did not stop. He just narrowed his hunting ground.

William Carter watched all this with growing despair. He documented everything in his private papers—the testimonies, the pattern, Reverend Grant’s essay, the violent response, the continued births. He had a comprehensive record of a systematic crime that was not legally a crime. Evidence that meant nothing. Truth that had no power.

In spring 1844, Carter made one final attempt. He requested a meeting with Virginia’s governor, James McDow, known for moderate views on slavery. Carter traveled to Richmond, presented his evidence, laid out the case with clinical precision—eighteen children now, all with distinctive emerald green eyes and blonde hair, all born to enslaved women in Henrio and Chesterfield counties, all fathered by one man: Jonathan Blackwell.

Governor McDow listened politely, reviewed the documents, asked careful questions, then gave Carter an answer that was both honest and devastating. “Mr. Carter, everything you’ve shown me is likely true. The pattern is undeniable. The evidence is compelling. Jonathan Blackwell is almost certainly guilty of exactly what you’re accusing him of. But under Virginia law, he has committed no crime. Enslaved women are property. Their owners might have civil complaints about damage to their property, but the women themselves have no standing to bring criminal charges. And even if they did, their testimony would not be admissible against a white man in court. There is no legal mechanism to prosecute Jonathan Blackwell. None. The law is working exactly as the legislature designed it.”

“So, we do nothing?” Carter asked, bitterness in his voice. “What would you have me do?” the governor replied, not unkind, just tired, just realistic. “Change the law. Make enslaved people persons under the law. Give them rights, legal standing, the ability to testify against white people. Do you understand what that would mean? It would unravel the entire system. Every plantation owner in Virginia would rise up against it. The legislature would never pass it. And if by some miracle they did, it would tear this state apart.”

“So the system is more important than justice?” “The system is justice, Mr. Carter. At least that’s what our laws say. Our laws define justice as the protection of property rights. Enslaved people are property. Their owners’ rights must be protected. That’s the foundation Virginia is built on. You can argue it’s wrong. You can call it immoral. You can rage against it, but you can’t change it through the legal system because the legal system is designed to preserve it.”

Carter left Richmond understanding he had reached the end. There was nothing more he could do. The law would not help. Public pressure would not work. The system was too strong, too entrenched, too invested in protecting men like Jonathan Blackwell. He went home to Ashland, filed his papers away in a strongbox, and tried to return to normal life. But normal felt impossible now.

Every day he ran his plantation, he was participating in the same system that had made the Blackwell case possible. Every day he benefited from the same laws that denied justice to those eighteen mothers.

The final birth in the pattern came in August 1844 at Fair View Plantation. The mother was Margaret, 21 years old. The baby was a girl, emerald eyes, blonde hair so pale it looked like spun silver. Margaret looked at her daughter and said seven words that would stay with everyone who heard them: “This is the last one he’ll make.”

Three days later, Jonathan Blackwell was found dead in his bedroom at Fair View. The official cause was heart failure. He was 39 years old, relatively healthy, no history of heart problems. The doctor, Frederick Morris, wrote “natural causes” on the death certificate without hesitation. The funeral was small, private, unremarkable.

But the enslaved people at Fair View knew better. They whispered about Margaret, about the strange plant that grew near the creek, about the tea she had been seen making three days before Jonathan died. They whispered about justice that came not from courts or laws, but from the desperate courage of a woman who decided some crimes demanded payment regardless of cost. They whispered and never told, never confirmed, never spoke where white people could hear.

Margaret was sold away from Fair View two weeks after Jonathan’s death. Edmund Blackwell claimed he needed to reduce his workforce, needed to raise capital. Margaret was sent to a plantation in Georgia, separated from her infant daughter, who remained at Fair View. The baby was raised by another woman in the quarters, grew up never knowing her mother, carrying emerald eyes and blonde hair as the only evidence of where she came from.

The other children grew up scattered across Virginia. Some remained on the plantations where they were born. Others were sold as they got older, their distinctive appearance making them valuable for certain purposes. The girls especially were sought after by traders who dealt in what the system called “fancy trade”—enslaved women with light, European features who could be sold for sexual exploitation to wealthy men who wanted the appearance of whiteness without the social complications of relationships with white women.

Grace, Ruth’s daughter, was sold when she was twelve, sent to New Orleans, where her features made her valuable. Ruth never saw her again. Never knew what became of her. Spent the rest of her life wondering if Grace was alive, if she was suffering, if she remembered her mother at all.

Thomas, Hannah’s son, was kept at Riverside until he was fifteen, then sold to a plantation in South Carolina. Hannah died two years later. Some said it was fever. Others said it was a broken heart, though that was not something doctors wrote on death certificates.

The pattern of birth stopped after Jonathan Blackwell’s death. No more emerald-eyed children appeared in Henrio or Chesterfield counties. The whispers faded. The scandal became history. The children remained, but as they were sold away, scattered across the South, the visible evidence of what had happened disappeared. Within ten years, most people had forgotten—or pretended to forget, which amounted to the same thing.

William Carter kept his records. When the Civil War came, when Virginia seceded, when fighting tore through the countryside, Carter hid his strongbox in the basement of his house. He survived the war, watched his plantation burn, watched the world he had known collapse. When slavery ended, when the Thirteenth Amendment made it unconstitutional to own human beings as property, Carter felt something unexpected. Not triumph, not vindication—just profound exhaustion.

He died in 1872 at age 84. His papers were inherited by his daughter, who married a Richmond lawyer. She found the strongbox, read the documents inside, and was horrified by what her father had documented—the systematic violation of enslaved women, the eighteen children with emerald eyes, Jonathan Blackwell’s impunity, Margaret’s possible revenge, the absolute failure of law and justice. She did not know what to do with this information. So, she did what many people do with uncomfortable truths: she hid it, put the strongbox back in the basement, told no one, let it sit in darkness.

The strongbox stayed there for 101 years, surviving fires and floods and the slow decay of time, until workers renovating the old house found it in 1973, pulled it out from behind a collapsed wall, opened it, and discovered a story Virginia had tried to forget.

The historian who examined the documents in 1973 was Dr. Eleanor Hayes, 42 years old, professor of American history at the University of Virginia. She had spent her career studying the antebellum South, focusing on the lives of enslaved people whose stories had been deliberately erased from official records. When construction workers brought her the strongbox, Dr. Hayes immediately understood what she was looking at.

William Carter’s handwriting was precise, methodical, the work of someone creating evidence that might matter someday. The testimonies were dated and signed with X marks—the women unable to write their own names, but leaving their mark as witness. The timeline was meticulous, showing Jonathan Blackwell’s presence at each plantation exactly three months before each birth. And the photographs—23 daguerreotypes, carefully preserved, showing children who should not exist.

Dr. Hayes spent six months verifying everything. She cross-referenced names with plantation records, tracked birth registries, death certificates, sale documents, traced property deeds, contacted descendants of the families involved. Every detail was accurate. William Carter had documented a systematic crime with scientific precision.

Dr. Hayes published her findings in the Journal of Southern History in December 1974. The article was titled “The Blackwell Case: Systematic Sexual Violation and Legal Impunity in Antebellum Virginia.” It was 37 pages long, heavily footnoted, filled with primary source documentation. It named names—Jonathan Blackwell, Edmund Blackwell, the plantation owners who had known and done nothing, the governor who admitted the law could not help, the system that protected a monster while denying justice to his victims.

The academic response was mixed. Some historians praised Dr. Hayes for bringing this story to light, for using rigorous methodology to document something slavery’s defenders had always denied—the systematic sexual exploitation of enslaved women, the calculated nature of the abuse, the complete legal immunity of the perpetrators. Others criticized her harshly, saying she was sensationalizing, using one extreme case to condemn the entire institution, letting modern moral standards cloud her judgment of historical context, that she should have been more balanced, more objective, less emotional.

Dr. Hayes ignored the critics. She knew what she had found. She knew what it meant. And she knew that the women whose testimonies filled William Carter’s documents deserved to have their truth told, even if it made people uncomfortable, even if it challenged accepted narratives about the Old South.

But publishing the academic article was only the first step. Dr. Hayes wanted to know what had happened to the children—the 23 babies born with emerald eyes between 1839 and 1844. Where had they gone? Had any survived to adulthood? Did they have descendants? Could those descendants be found?

The search took years. Dr. Hayes worked with genealogists, local historians, amateur researchers. They traced sale records, found death certificates for some who died young, marriage records for others who survived to adulthood, trails that led to descendants living in the 1970s—people who had no idea their great-great-grandparents had been part of this story.

Grace, Ruth’s daughter, the first child born in the pattern, was sold to New Orleans at age twelve. Records showed she was purchased by a wealthy merchant for “domestic service,” a euphemism everyone understood. Grace lived in the household for six years, then in 1857, she was freed. Manumission papers showed she was granted freedom and left a small sum of money in the merchant’s will. Whether this was conscience or calculation, no one could say.

Grace married a free black man named Marcus Freeman in 1858. They had four children, raised them in New Orleans through the Civil War and Reconstruction. Grace died in 1892 at age 53, her death certificate listing pneumonia as the cause. But her granddaughter, interviewed by Dr. Hayes in 1976, remembered different stories—stories Grace told late at night, about Virginia, about Ruth, about a white man with emerald eyes who hurt people and got away with it until someone stopped him.

“You mean Margaret?” Dr. Hayes asked—the woman some say poisoned Jonathan Blackwell. “Grandma Grace never said it directly, but she smiled when she told that part of the story. Said, ‘Justice doesn’t always come from courts. Sometimes it comes from courage. Sometimes it comes from women who decide enough is enough.’”

The granddaughter, Sarah Freeman Baptiste, was 74 years old, living in New Orleans. When Dr. Hayes asked if she had photographs of her grandmother, Sarah brought out a small wooden box—inside were three photographs: Grace at age 20, 35, and 48. In each, those emerald eyes stared out, bright, clear, unmistakable—beautiful, haunted, defiant.

“She never talked much about her childhood,” Sarah said, holding the photographs carefully. “Said it was too painful. But she made sure we knew where we came from, made sure we understood that we survived. Survival itself was resistance.”

Dr. Hayes found 11 other descendants of the emerald-eyed children, scattered across the country—some in Louisiana, some in Georgia, some who migrated north during the Great Migration. Most did not know the full story of their ancestors. They knew family legends, fragments, pieces, but Dr. Hayes brought them documentation, testimonies, photographs—the proof that their ancestors’ suffering had been real, documented, preserved by a white man who tried to help even when the law made help impossible.

The descendants had mixed reactions. Some were grateful—finally, their ancestors were being recognized, their pain acknowledged. Others were angry—feeling the story was being told by outsiders, their family trauma made public without consent. A few wanted nothing to do with it, wanted to leave the past buried, move forward without carrying that weight.

Dr. Hayes understood all of it. Trauma does not disappear with time—it gets passed down, transformed, carried in different ways by different generations. The children born with emerald eyes grew up marked by their origins, struggling with identities that did not fit neatly into any category. Their children inherited that complexity, and their children’s children, all the way down to people living in the 1970s who still felt the echoes of what Jonathan Blackwell had done more than 130 years earlier.

In 1978, Dr. Hayes organized a gathering. She invited all the descendants she could locate, along with historians, journalists, and community members interested in the story. The event was held at a church in Richmond, not far from where Mount Zion had stood before it burned. Twenty-three people attended—some descendants of the emerald-eyed children, others descendants of the mothers, families that survived and remembered.

The gathering was emotional. People cried. They shared stories from grandparents and great-grandparents. They looked at photographs of the children, seeing family resemblances across generations. They held the documents William Carter had preserved, reading the testimonies their ancestors had given, hearing voices silenced for more than a century.

One woman, a descendant of Hannah from Riverside, stood and spoke. Her name was Dorothy Mitchell, 56 years old, a schoolteacher from Atlanta. “My great-great-grandmother Hannah never recovered from what happened to her,” Dorothy said, her voice shaking. “She raised my great-grandfather, Thomas, but everyone said she was never really there, never really present. Something in her broke that couldn’t be fixed. She died young, heartbroken, people said. But it wasn’t a broken heart. It was a shattered soul. Knowing that now, knowing the truth of what was done to her, it doesn’t make it better, but it makes it real. It gives her pain a name. It honors what she survived.”

Others spoke—descendants of Ruth, Mary, Esther, and the women whose names were recorded in William Carter’s careful handwriting. They spoke about inherited trauma, family silences, the weight of knowing your existence came from violation. They spoke about resilience, survival, the strength it took to raise children in those circumstances, to love them despite everything, to pass on life even when life had been so cruel.

And they spoke about justice—the kind that never came through courts or laws, the kind Margaret might have delivered with poison in tea, the kind that came from simply surviving, from refusing to be erased, from existing as evidence that the system’s crimes could not be completely buried.

Dr. Hayes continued researching the case for the rest of her career. She published two more articles, then a book in 1983 titled “Emerald Eyes: Sexual Violence and Legal Immunity in the Antebellum South.” The book used the Blackwell case to examine broader patterns of systematic sexual exploitation under slavery—the way the law was structured to deny enslaved women any protection, the way plantation owners and their sons could violate women with absolute impunity, the way the children born from those violations were evidence that could not be spoken, proof that could not be acknowledged, truth that had to be hidden to preserve the fiction that slavery was benevolent.

The book won awards. It became required reading in many university courses on American history. It brought the Blackwell case into the broader conversation about slavery’s horrors, about the specific ways enslaved women suffered, about the intersection of racial and sexual violence that defined the institution.

But more importantly, it gave the women and their descendants something they had never had—recognition, acknowledgment, a place in history that was not hidden or erased or explained away. Ruth, Hannah, Esther, Mary, Abigail, Rebecca, Sarah, Catherine, Elizabeth, Margaret, and the others whose names appeared in the records were no longer just property, no longer just victims. They were human beings whose suffering mattered, whose voices deserved to be heard, whose truth survived despite every attempt to bury it.

The Blackwell family tried to suppress the book. Descendants of Edmund Blackwell, still living in Virginia, still influential, hired lawyers to challenge Dr. Hayes’s research. They claimed the documents were fraudulent, that William Carter had fabricated the testimonies, that Jonathan Blackwell had been slandered. They threatened lawsuits, pressured the publisher, tried everything to prevent the story from spreading. They failed. The documentation was too solid, the evidence too compelling, the photographs too real. You could deny testimony. You could question documents. But you could not explain away 23 children with emerald eyes who had been photographed, documented, tracked through sale records and birth registries. They existed. Their descendants existed. The truth existed.

In 1991, the state of Virginia erected a historical marker near the site where Fair View Plantation once stood. The marker read: “On this site stood Fair View, a tobacco plantation where systematic sexual violence against enslaved women occurred between 1839 and 1844. Twenty-three children were born from these crimes, marked by distinctive features that served as evidence the legal system refused to acknowledge. This marker stands in memory of the victims and in recognition that justice delayed for more than a century is still justice owed.”

The marker was vandalized twice, torn down once, but replaced each time. Eventually, people stopped destroying it. Eventually, it became part of the landscape—a reminder that could not be erased.

Dr. Eleanor Hayes died in 2006 at age 75. She spent 33 years researching and writing about the Blackwell case, about the women who suffered, the children who survived, the descendants who carried that history forward. Her papers and research materials were donated to the Library of Virginia, where they remain accessible to anyone who wants to understand this chapter of American history.

The descendants of the emerald-eyed children continue to gather occasionally—not every year, but sometimes. They stay connected through the shared knowledge of where they came from, what their ancestors survived, how their very existence is evidence of both horror and resilience. Some have done DNA testing, confirming what the photographs and documents already showed—they carry Jonathan Blackwell’s genes. The man who violated their great-great-grandmothers is in their blood, in their features, in the emerald eyes that still appear in some family lines generation after generation.

It’s a complicated inheritance—DNA from a rapist, features that mark them as connected to violence. But they have chosen to see it differently—not as shame, but as survival. Their ancestors endured the unendurable, raised children under impossible circumstances, passed on life despite everything. That’s the legacy they claim—not the crime, but the courage that followed it.

The story of Virginia’s emerald-eyed children reveals something essential about American slavery that is often obscured in sanitized historical narratives. The institution was not just about labor exploitation or economic calculation; it was about absolute power wielded over people legally stripped of their humanity. It was about the systematic denial of personhood, the reduction of human beings to property, the creation of a legal framework that made the most monstrous crimes invisible.

Jonathan Blackwell was not an aberration. He was the system working exactly as designed—a white man with access, opportunity, and complete legal immunity. The law protected him because the law was written to protect men like him. The women he violated had no recourse because they were property. Their children became property. Their pain became invisible. Their truth became unspeakable.

What makes the Blackwell case unusual is not that it happened—it’s that it was documented. That William Carter preserved evidence, that Reverend Grant published testimonies, that Dr. Hayes found the records and brought them to light. Most cases like this disappeared without a trace. The women suffered in silence. The children grew up marked but unnamed. The perpetrators died peacefully, their crimes buried with them.

But this case survived. The truth survived. Twenty-three children with emerald eyes became hundreds of descendants who exist today, carrying that history in their genes and their memories. They are living evidence that some truths refuse to stay buried.

The documentation matters. The preservation of even the most painful stories serves justice in ways that take generations to understand. The system that made the Blackwell case possible no longer exists. Slavery ended. The Thirteenth Amendment declared that owning human beings as property was unconstitutional. Laws changed to recognize that all people, regardless of race, have legal standing and rights. The absolute immunity that protected men like Jonathan Blackwell was abolished.

But the legacy remains—in the descendants who still gather to remember, in the historical markers that name the truth, in the academic research that refuses to let these stories disappear, in the knowledge that justice, however delayed, however incomplete, still matters. Naming crimes matters. Honoring victims matters. Preserving truth matters, even when the truth is terrible.

Ruth died in 1868 at age 59. She lived long enough to see slavery end, to be legally free, to know that the system that made her violation invisible no longer had the force of law. But she never saw Grace again. Never knew if her daughter survived, if she was free, if she remembered Virginia and the mother who tried to protect her.

Ruth was buried in a small cemetery outside Richmond. Her grave has no marker. Her name appears in no monument. But her testimony survives in William Carter’s documents. Her voice speaks across 150 years, and her great-great-great-grandchildren know her story.

That’s what survives—not the crime, not the perpetrator’s power, but the victim’s truth. Not the system’s immunity, but the documentation that preserves what the system tried to hide.

Virginia discovered 23 slave babies with emerald eyes and blonde hair, all from one father. The pattern was documented. The truth was preserved. The descendants survive. And the story refuses to be forgotten—no matter how many times people try to bury it, vandalize the markers, or deny what happened.

Some truths are stronger than the systems that try to suppress them. Some evidence survives despite everything. And sometimes, justice comes not from courts or laws, but from the simple act of remembering, of speaking names, of honoring those who suffered by refusing to let their stories disappear into silence.

What are your thoughts on this case? How do you think we should remember and honor the victims of systematic violence whose suffering was invisible under the law? Leave your comment below and share your perspective. If you found this story as important as I did, please hit that like button, share this video with someone who values historical truth, and subscribe for more deep investigations into America’s buried past. Thank you for listening, and I’ll see you in the next story.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load