Vivian Vance FINALLY Reveals the Untold Truth Behind “I Love Lucy”—The Real Story Fans Never Knew

For decades, the legend of Vivian Vance’s role on “I Love Lucy” has been shrouded in myth, gossip, and half-truths. Most fans believed she signed a bizarre contract forcing her to gain weight just to make Lucille Ball look thinner. But now, after years of Hollywood whispers and speculation, the truth has finally come out—and it’s nothing like the stories you’ve heard.

Vivian Vance, born Vivian Roberta Jones in Cherryvale, Kansas in 1909, was never meant for a quiet life. Raised under strict Methodist rules and a mother who believed acting was a ticket to hell, Vivian’s earliest years were a battle between her natural spark and her family’s relentless efforts to snuff it out. Her mother’s disapproval was more than a passing annoyance—it was a war that shaped Vivian’s spirit and haunted her for years. At home, she was always the outsider, craving the stage and freedom while her family tried to keep her grounded, silent, and ashamed.

But Vivian’s fire couldn’t be contained. After her family moved to Independence, Kansas, she found solace in school drama and the encouragement of a teacher who saw her potential. She became “Viv” to her friends, shedding the chains of her family name and eventually adopting “Vance” from folklorist Vance Randolph—a sign that she was ready to write her own story. With $50 and a suitcase, she left Kansas for New York, determined to make her mark. She worked as a waitress by day, auditioned by night, and survived on little more than hope and grit.

Vivian’s early career was a testament to resilience. She became a star at the Albuquerque Little Theater, where her performances were so beloved that locals renamed the building in her honor. She sang “My Man” and brought the house down. By 1932, she landed a chorus role in the Broadway musical “Music in the Air,” and by 1941, she was starring alongside Danny Kaye and Eve Arden in “Let’s Face It,” a smash hit that ran for 547 performances. But even as she conquered the stage, her personal life was in turmoil. Her first marriage ended in heartbreak, and her second, to actor Philip Ober, was marked by jealousy and violence. Ober’s insecurity about Vivian’s success led to physical abuse, and the emotional scars ran deep.

Vivian suffered in silence. She endured black eyes and breakdowns, all while delivering performances that made audiences laugh and cry. She found solace in therapy and, later, in visiting psychiatric hospitals—not as a celebrity, but as someone who understood pain and wanted others to know they weren’t alone. Her battles with anxiety and mental illness were lifelong companions, rooted in childhood trauma and toxic relationships.

Hollywood, for all its glitz, offered little refuge. When Vivian moved to California to try her hand at film, she found the doors mostly closed. She appeared in just two movies before television finally gave her a second chance. In 1951, at age 42, she was cast as Ethel Mertz in “I Love Lucy.” The role would make her a household name, but it came with its own set of burdens.

The infamous “weight contract” was never real. Lucille Ball made it up as a joke at a party, scribbling silly rules about gaining five pounds a week and never being funnier than Lucy herself. The world, hungry for gossip, took the joke seriously, and the myth lived on for years. In reality, Vivian’s weight fluctuated naturally, and while Lucy may have wanted to look more glamorous by comparison, there was never any official agreement. Still, the show’s producers worked hard to make Vivian seem older and less glamorous—tight clothes, awkward makeup, anything to keep Lucy in the spotlight.

Vivian’s relationship with her on-screen husband, William Frawley, was famously toxic. She joked that he looked more like her grandfather than her husband, and he never forgave her. Their mutual dislike became part of the show’s chemistry, but off-camera, it was a source of constant tension. Frawley’s drinking and antagonism pushed Vivian to demand separate dressing rooms, and the two avoided each other whenever possible. When offered a spin-off about Fred and Ethel, Vivian refused—no amount of money was worth working with Frawley again.

Despite the drama, Vivian and Lucy found a rhythm. Their on-screen fights often mirrored real-life disagreements, but the magic they created together was undeniable. In 1954, Vivian made history as the first woman to win an Emmy for Outstanding Supporting Actress, a victory that created a new category for side characters and cemented her legacy. But the success was bittersweet. The Emmy made her a legend, but it also trapped her in the role of Ethel, overshadowing her earlier achievements and limiting her opportunities.

Behind the laughter, there was pain. The iconic chocolate factory scene, where Lucy and Ethel frantically stuff chocolates on a speeding conveyor belt, was pure comedy gold for viewers. For Vivian, it was torture—take after take, she ate so much chocolate she was sick for days. The same went for Lucy’s famous “Vitameatavegamin” sketch; the prop tonic was real alcohol, and Lucy was actually drunk by the final takes. Early television often pushed actors to their limits, and the cost was real.

Vivian’s fame brought fortune but also fear. As “I Love Lucy” became a global phenomenon, she received thousands of fan letters each week—some sweet, some scary. She had to hire her own security just to feel safe in public. The world loved Ethel, but few knew the woman behind the character was struggling with anxiety, heartbreak, and the constant pressure to live up to an image.

Her personal life never stopped hurting. Her first marriage was a nightmare, escaping to a women’s shelter to avoid her husband’s jealousy and abuse. Philip Ober, her second husband, hit her so badly during “I Love Lucy” that she showed up to work with a black eye, barely concealed by makeup. Lucille Ball saw the damage and demanded Vivian leave him, but nothing could erase the pain. Vivian’s inability to have children was another silent sorrow. She miscarried early in her marriage to Ober, and watching Lucy raise her own children was a constant reminder of what she’d lost. Vivian poured her love into mentoring young actresses, hoping to fill the void.

By the 1970s, Vivian had traded stage and sitcoms for Maxwell House coffee commercials, playing the cheerful Maxine. The ads were cozy and familiar, but Vivian knew her days of chasing dramatic roles were over. She was loved for one role, forgotten for everything else. In 1977, Lucille Ball invited her for a CBS special, “Lucy Calls the President.” Vivian, fighting breast cancer and recovering from a stroke, gave her all. On screen, she was still the old Viv—charming, funny, sharp—but the truth was cruel. She was sick, and her final appearances were a testament to her resilience.

Vivian Vance’s story isn’t just about fame or comedy—it’s about survival. She battled mental illness, abusive relationships, and a system that tried to box her in. She won the very first Emmy for supporting actress, but it came at a cost. In her final days, she dictated letters exposing the industry’s sexism and the barriers she faced. She wanted to direct, but producers told her it wasn’t ladylike. Hollywood tried to silence her, but her words live on.

When Vivian died on August 17, 1979, the world lost more than Ethel Mertz. It lost a woman who fought for dignity, who refused to be defined by anyone else’s standards, and who, despite everything, made millions laugh. Her final reunion with Lucille Ball was filled with laughter and tears—a testament to a friendship that survived the storms of fame.

Vivian Vance’s truth is finally out. The myths are gone, replaced by a story of heartbreak, courage, and the relentless pursuit of self-worth. For every fan who loved Ethel, there’s a deeper story worth knowing—a story that proves the brightest stars often shine through the darkest nights.

News

After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer walked into my office and smugly handed me divorce papers, saying, “She’ll be taking everything—the house, the cars, and full custody. Your kids don’t even want your last name anymore.” I didn’t react, just smiled and slid a sealed envelope across the desk and said, “Give this to your client.” By that evening, my phone was blowing up—her mother was screaming on the line, “How did you find out about that secret she’s been hiding for thirteen years?!”

Checkmate: The Architect of Vengeance After twelve years of marriage, my wife’s lawyer served me papers at work. “She gets…

We were at the restaurant when my sister announced, “Hailey, get another table. This one’s only for real family, not adopted girls.” Everyone at the table laughed. Then the waiter dropped a $3,270 bill in front of me—for their whole dinner. I just smiled, took a sip, and paid without a word. But then I heard someone say, “Hold on just a moment…”

Ariana was already talking about their upcoming vacation to Tuscany. Nobody asked if I wanted to come. They never did….

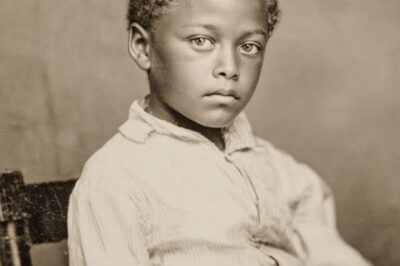

The Impossible Mystery Of The Most Beautiful Male Slave Ever Traded in Memphis – 1851

Memphis, Tennessee. December 1851. On a rain-soaked auction block near the Mississippi River, something happened that would haunt the city’s…

The Dalton Girls Were Found in 1963 — What They Admitted No One Believed

They found the Dalton girls on a Tuesday morning in late September 1963. The sun hadn’t yet burned away the…

“Why Does the Master Look Like Me, Mother?” — The Slave Boy’s Question That Exposed Everything, 1850

In the blistering heat of Wilcox County, Alabama, 1850, the cotton fields stretched as far as the eye could see,…

As I raised the knife to cut the wedding cake, my sister hugged me tightly and whispered, “Do it. Now.”

On my wedding day, the past came knocking with a force I never expected. Olivia, my ex-wife, walked into the…

End of content

No more pages to load