Neighbors in the San Gabriel Valley still talk about the boy with the quick smile, the sharper wit, and the rare bone disorder that doctors said would claim his life before second grade. His name was Roy Lee “Rocky” Dennis, born December 4, 1961, in Glendora, California. To most medical professionals of the era, his case—cranio-diaphyseal dysplasia, sometimes called “lionitis”—was a heartbreaking inevitability. To his mother, Florence “Rusty” Tullis, it was a dare. She lit a cigarette, listened, and told them they were wrong.

An X-ray after a minor toddler fall revealed the first undeniable signs: skull bones thickening with unusual speed and density, nerve passages narrowing, sinuses filling with bone. Radiologists compared notes; specialists pored over scans. The consensus was grim—very few documented cases worldwide, no cure, no effective treatment, a prognosis measured in years you could count on one hand. The medical literature described what the eye could not fully comprehend: a skull slowly turning from shelter to pressure chamber, squeezing vision, hearing, and breath.

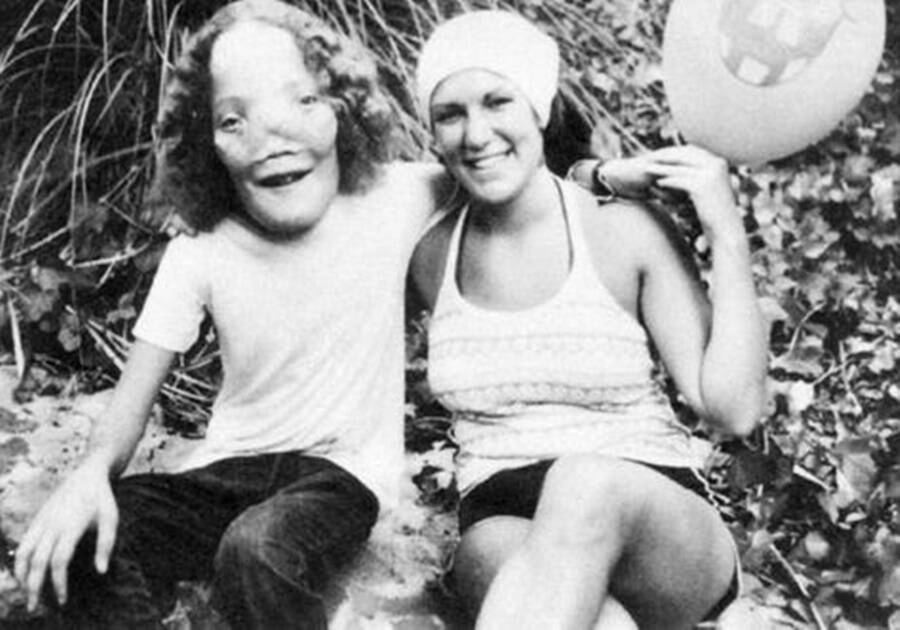

But Rocky’s world wasn’t a journal abstract. It was a small California home saturated with music, posters, and the low rumble of motorcycles outside. Rusty, who found belonging in a biker community known for its code of fierce loyalty, built a life where her son wasn’t a diagnosis—he was simply Rocky. She taught him to get ahead of the joke, to meet stares with humor, to claim his place in the room. “If I make you uncomfortable, you can move,” he’d tell people matter-of-factly. “I can’t change my face.”

The battles she chose were everyday and enormous. When schools hesitated, she pushed. When whispers started, she spoke louder. Rocky walked into classrooms some thought he’d never enter, and he kept walking—through reading lists, geography quizzes, and the hearts of teachers who learned quickly they’d be teaching a boy with a mind as expansive as his courage. He wasn’t an object lesson in pity; he earned respect the old-fashioned way, with work, wit, and warmth.

Behind the victories, the disease moved with quiet persistence. As a teen, Rocky began to feel the crush of his condition: headaches that darkened entire days, eyesight that dimmed at the edges, fatigue that arrived earlier and stayed longer. Rusty doubled down on what had always worked—routine, laughter, guided relaxation for the pain, long talks about plans as if there were all the time in the world. He kept up with school, played guitar when he could, traded jokes when he couldn’t, and wrote poems that sounded like any kid’s backyard inventory of small joys and smaller annoyances. These things are good… the sun shining on my face. These things are a drag… the sun shining on my face. The line lingered—equal parts humor and truth from a boy who understood the weather of life better than most.

By 1978, Rocky was 16—nine years beyond the most generous predictions. Some days brought ease, the kind of quiet that feels like a truce. He reassured his mother when the roles should have been reversed. He wasn’t afraid, he said. He didn’t want her to cry. They talked long and late on his last evening, trading memories of road trips, classrooms, music turned up too loud. He fell asleep and did not wake. On October 4, 1978, Rocky Dennis died peacefully at home, leaving behind a silence that was almost physical, a house that suddenly seemed too big, and a mother determined that his life would not be flattened into tragedy.

What followed was not a Hollywood ending so much as a human one, magnified. Rusty took Rocky’s story to anyone who would listen—schools, bike rallies, community groups—insisting that people see beyond the rare diagnosis to the everyday kid who outlasted predictions and outloved expectations. The story found its way to screenwriter Anna Hamilton Phelan, and then to film. In 1985, Mask introduced millions to a boy whose face people thought they couldn’t see past, and to a mother who refused to let them look away. Cher’s portrayal of Rusty won Best Actress at Cannes; Eric Stoltz’s performance helped audiences recognize the person beneath the condition. The movie took liberties, as films do, but it captured the essential truth: Rocky wasn’t a symbol; he was a son, a friend, a student, a kid with a guitar and a gift for disarming a room.

Back home, his legacy was more granular and, in a way, more powerful. Teachers remembered how he changed the temperature of a classroom—how curiosity spread when he raised his hand, how laughter arrived when he cut through tension with a line that landed just right. Classmates remembered feeling seen. Strangers remembered feeling checked, then grateful, as their snap judgments dissolved into conversation. In the small economy of daily life, Rocky made deposits that compounded.

There’s a temptation to turn stories like his into cautionary tales or miracle narratives. Rocky’s life was neither and both. He lived with a condition so rare that most physicians never encounter it. He also lived like a teenager—stashing jokes, nursing crushes, fighting headaches, and dreaming as if time were on his side. The medical facts were unyielding: bone thickening that medicine of the era could not halt, nerve pathways narrowing with no safe surgical fix then available, a prognosis backed by case histories that had ended sooner, harder. The human facts were equally immovable: a mother’s defiance, a kid’s refusal to be defined by the cruelest thing that ever happened to him, and a community’s lesson in seeing.

If you’re wondering how to tell this story without slipping into exploitation or exaggeration, the answer might be simpler than it seems. You stay with what’s true. You avoid dressing diagnosis as destiny or grief as spectacle. You resist mythologizing hardship into magic and let the real stakes breathe: a rare disease that medicine couldn’t treat at the time, a child who outlived predictions by years, and a mother who built a life around possibility rather than prognosis. You cite what’s known—the dates, the diagnosis, the film that followed—and you allow the unknowns to remain unknown. You don’t inflate; you illuminate.

That approach isn’t just ethical; it’s effective. Readers recognize when a story honors its subject. They can feel the difference between manipulation and meaning. Keeping the narrative grounded in verifiable detail while focusing on character—the classroom quips, the backyard poems, the way Rusty trained her son to meet mockery with mastery—builds trust. It also builds momentum. People don’t turn away from truth well told; they lean in. And when the storytelling centers dignity, the instinct to report content as false drops because the story doesn’t need embellishment to be extraordinary.

In the end, Rocky’s enduring impact lives in the soft skills that don’t trend but travel: the grace to look again, the courage to enter a room as you are, the strength to insist on a full life even when the calendar won’t cooperate. His story widened a lens in classrooms and living rooms long before it reached a movie screen, and it continues to do so now, decades later, as new readers find their way to a name that medicine once filed under anomaly and a community now remembers as neighbor.

He wasn’t supposed to make it to kindergarten. He made it to 16. In those years, the boy who “shouldn’t have lived” managed to teach a lesson that outlives any diagnosis: that the sum of a life isn’t measured only in years or outcomes, but in how bravely and generously it’s lived. That’s not myth. That’s the record—an American story about love defying prediction, not disease, and a young man whose greatest legacy may be the way he helped the rest of us learn to see.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load