The first time I heard the name Constance Peton, I was twelve years old, sitting in the back pew of St. Joseph Catholic Church while Father Antoine recited parish history. He spoke in a low voice, as if wary of the shadows that clung to the corners of the sanctuary, and when he mentioned Willowbrook Plantation, the air seemed to thicken with the hush of old secrets. My father, a practical man, would later dismiss such stories as “bayou nonsense,” but I remembered the look in Father Antoine’s eyes—a flicker of fear, a glimmer of something unspoken.

Years passed before I learned the truth—or as much of it as anyone ever could. Willowbrook was not just another ruined house lost in the tangle of Lafor Parish. It was a wound in the land, a place where grief and ambition had conspired to birth something unnatural, something that science, law, and faith had each failed to contain.

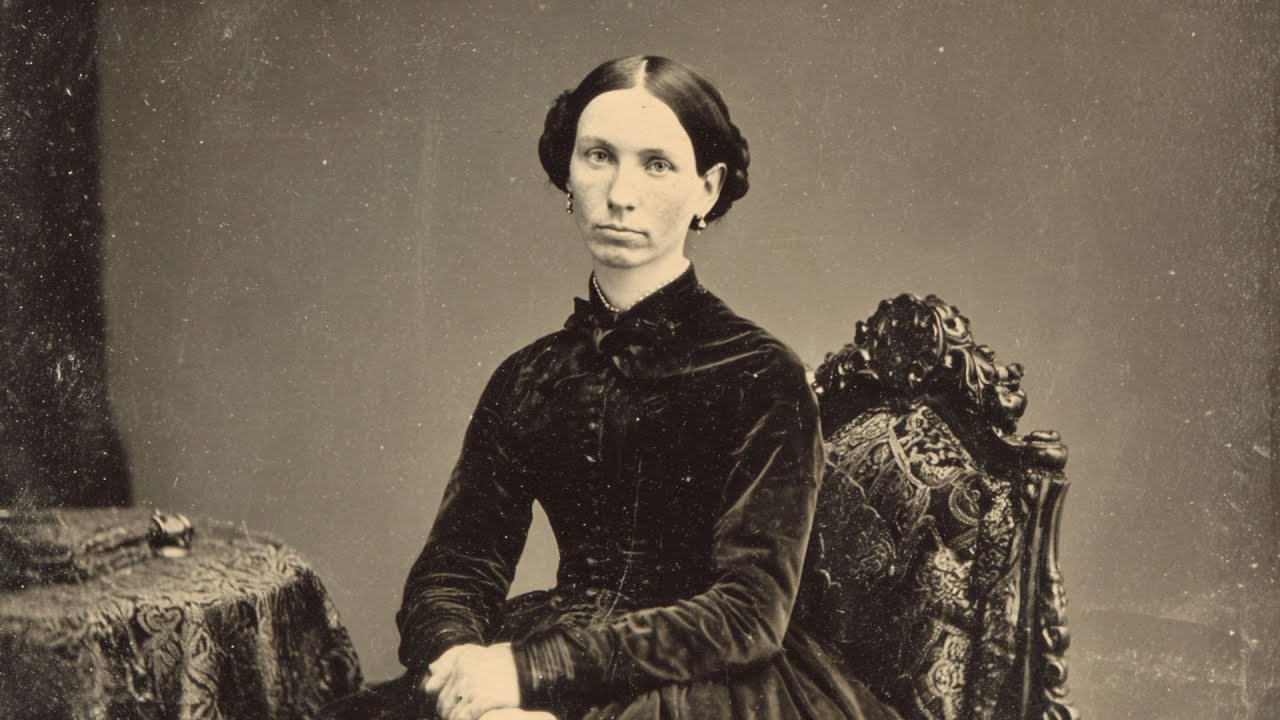

In the spring of 1873, Constance Peton arrived at Willowbrook, a widow draped in black, her satchel worn and her reputation darker still. The plantation had once been the pride of the delta, three stories of white columns and wraparound galleries rising above cypress groves and marsh. But the war had hollowed it out. Fields lay fallow, the slave quarters stood empty, and the only voices were those of Constance and her housekeeper, Margaret Tibido—a local woman whose devotion would prove both her salvation and her undoing.

Margaret’s testimony, preserved in the parish records, paints a portrait of those first weeks: Constance drifting through empty halls, pausing at doorways, her gray eyes scanning the shadows as if searching for something that refused to be found. She made no effort to restore the plantation’s fortunes. Instead, she wrote letters—hundreds of them—burned each one after sending, and forbade Margaret from ever entering the office. The air in that room was thick with the scent of scorched paper, and Margaret, loyal but frightened, obeyed.

The community watched with a mixture of curiosity and concern. The widow was young, beautiful in a severe way, and her isolation unsettled the parish. She refused invitations, declined church services, and turned away visitors with a cold courtesy that brooked no argument. Dr. Edmund Rouso, who had attended Jeremiah Peton in his final days, tried to check on her. Margaret met him at the gallery, her composure cracking as she admitted that her employer spoke to empty rooms, set places at the table for invisible guests, and referred to herself in the plural—“We have decided,” she would say, “Our plans require…”

The doctor was denied entry, and the house remained sealed to outsiders. Yet the rumors grew. Lights flickered in the fields at night, and neighbors reported the sounds of digging, always between midnight and dawn. Most dismissed these as the fancies of frightened minds, until young Thomas Landry, hunting rabbits in the cypress grove, discovered freshly turned earth near an old storehouse. Sheriff August Budro was summoned, and his investigation revealed a pattern of nocturnal activity that defied explanation.

Constance greeted the sheriff with politeness, her parlor arranged in a circle of chairs as if awaiting a gathering that never came. She spoke of agricultural experiments, showed sketches and notes, but the excavations were too small, too scattered, too carefully concealed to serve any farming purpose. Margaret, pressed for details, described trunks stored in the office, medical and scientific texts far beyond a widow’s usual interests, and daily routines that grew stranger by the week.

By winter, the fear had grown palpable. Residents saw figures moving through the fields during snowfall, their steps leaving no tracks. Always before dawn, always multiple shapes where only two women were known to live. Dr. Rouso returned in February, finding Constance changed—thin, hollow-eyed, her hands trembling as she poured tea set for four. She addressed empty chairs, paused to listen to unheard responses, and spoke of research that would revolutionize human understanding. When the doctor suggested rest, she grew fierce, insisting that her work was too important to abandon.

During their conversation, Rouso heard voices from the upper floor—distinct, varied, impossible for one person to produce. Margaret later confessed she had heard the same for weeks, assuming Constance was reading aloud, but the voices were too many, too different.

Spring brought the discovery that forced official intervention. Tax assessor Henri Budro’s team found no livestock, no crops, only chemical odors and concealed excavations—twelve distinct sites, each carefully maintained, marked by stones in strange patterns. Outbuildings showed signs of modification: windows covered, locks installed, ventilation designed to contain rather than circulate air. The chemical smell was strongest near these structures, but no one could identify the substances.

Sheriff Budro, Dr. Rouso, and Father Antoine returned for a welfare check. The house was in disarray—drawers open, papers scattered, furniture overturned. Margaret sat in the kitchen, hands folded, her mind fractured. “We’ve finished the work,” she repeated, “Everyone’s gone to their proper places.” She spoke of conversations with absent people, insisted the plantation was full of residents who slept during the day, and described scientific equipment, medical procedures, and collaborations with distant researchers.

The search revealed hundreds of letters, journals, and diagrams documenting experiments in human behavior modification. Subjects were identified only by numbers; records described changes in speech, physical response, psychological state. Environmental controls, sensory modification, compliance reinforcement—techniques decades ahead of contemporary science. Outbuildings contained chemical equipment, restraining devices, anatomical charts annotated with Constance’s precise script.

Excavation sites revealed evidence of use—remains of small structures, improvised living quarters, storage for research materials. Personal items, clothing, and sleeping arrangements suggested a larger population than official records acknowledged. But the identities and whereabouts of these residents remained unknown.

The correspondence network stretched across states, linking Constance to medical professionals in New Orleans, Atlanta, Richmond. Letters discussed theories of perception, memory, and the creation of compliant subjects for therapeutic intervention. Her library included recent publications on neurology and psychology, with marginal notes demonstrating a mastery of complex concepts.

The official investigation ended in June 1874. Constance Peton had vanished, leaving behind evidence of systematic human experimentation. No victims were identified, no crimes could be proven. Margaret was sent to the Sisters of Charity in New Orleans, her mind never recovering. She spoke of Willowbrook as if still living there, insisting that Constance’s research had succeeded in ways science refused to acknowledge.

Attempts to trace Constance’s collaborators led nowhere—addresses were fictitious, recipients denied involvement, and the few who responded dismissed her as an amateur. Father Antoine’s report to the bishop, sealed in diocesan archives, concluded that the plantation had been the site of an attempt to undermine human free will through “scientific possession.” He recommended consecration and destruction of the property, but only the former was heeded.

The plantation was sold at auction in 1876, but owners came and went, driven away by strange occurrences—lights moving through abandoned buildings, voices carrying across fields, chemical odors lingering around outbuildings. Workers refused to stay after dark, citing feelings of being watched and sounds suggesting invisible crowds.

In 1887, Dr. William Hartwell of Tulane University conducted the most detailed investigation. His chemical analysis revealed residues consistent with experimental anesthetics and substances affecting perception and memory. Excavations were mathematically precise, suggesting knowledge of underground water systems and soil conditions. Environmental modifications—acoustics, lighting, air circulation—were designed to optimize conditions for behavioral manipulation.

Hartwell found hidden compartments in the office containing maps marked with isolated farmsteads, notes on daily routines, and recruitment criteria for subjects. Missing person reports from 1873-74 revealed patterns of unexplained disappearances, though direct connections remained elusive. Success documentation described subjects who underwent “consciousness restructuring,” achieving “optimal compliance and enhanced receptivity.” These records suggested Constance’s experiments had succeeded in fundamentally altering personality and behavior.

The fate of these subjects was never resolved. Hartwell noted cases in neighboring states of people found wandering with no memory of their identities. The final investigation occurred in 1923 when the Louisiana Historical Society purchased the property. Fresh excavations, modified structures, and chemical residues indicated continued use long after Constance’s disappearance. Researchers reported psychological distress—feelings of being observed, memory loss, difficulty concentrating—while working at Willowbrook. The society abandoned plans for preservation.

In 1947, Willowbrook Plantation burned in a fire of unknown origin. Volunteer firefighters reported the blaze burned with unnatural intensity, producing chemical smoke reminiscent of laboratory fires. The ground itself burned differently, revealing the full extent of the modifications. The land remained vacant until 1961, when the state purchased it for wildlife preservation. Equipment malfunctions, navigation difficulties, and psychological effects plagued park rangers and researchers. In 1968, the area was reclassified as unsuitable for public access, removed from all official documentation.

Today, the site exists in administrative limbo. No records acknowledge its history, maps show only unmarked wetlands, but locals report vehicles breaking down, electronic devices failing, and persistent lights and sounds. The case of Constance Peton and Willowbrook Plantation remains one of the most documented yet inexplicable events in Louisiana history. Evidence suggests systematic experimentation in psychological manipulation decades ahead of its time, but the fate of the experimenter and her subjects is unknown.

The silence is telling. Research that should have transformed psychology was suppressed. The disappearance of records, restriction of access, and suppression of information suggest someone recognized the implications and took steps to ensure secrecy. The scientific community’s silence is the most eloquent testimony—some discoveries are too dangerous to be known.

In 1969, Dr. James Morton of Charity Hospital published a brief paper on “inherited behavioral anomalies” in certain Louisiana families. His research, conducted without sanction, documented psychological compliance and memory dysfunction transmitted across generations in families with ties to Lafor Parish. The paper was retracted within weeks, and Morton was transferred to administrative duties, ending his career. But copies circulated among researchers, raising questions about the long-term effects of Willowbrook.

Families identified in Morton’s research displayed unusual compliance, difficulty forming independent memories, and a tendency to accept contradictory information. Oral traditions mentioned ancestors who worked with the widow, but details were missing, records altered or erased. The pattern was too consistent to be accidental.

If Constance Peton’s research succeeded, and its effects could be inherited, the scope of the Willowbrook legacy extended far beyond her immediate subjects. Hundreds of individuals could carry psychological modifications implemented during those months. The suppression of information, administrative interference, and coordination of efforts to prevent public awareness point to recognition at the highest levels that the widow’s research had implications for national security. The possibility of creating compliant populations was a threat too great to acknowledge.

Nearly 150 years after Constance Peton arrived at Willowbrook, the physical evidence is gone, the witnesses are dead, and the records purged. Yet the legacy continues in forms impossible to detect or measure. The techniques may have been refined and deployed elsewhere. Somewhere in classified files, the true scope of Willowbrook influences decisions that shape millions of lives.

The story of Willowbrook Plantation is a reminder that some knowledge comes at a cost too high to bear. The widow may have unlocked secrets of consciousness that should have remained hidden, and her legacy may still shape our world in ways we cannot perceive. The greatest horror is not what we know, but what we can never know—how many minds were changed, how many lives altered, how many descendants carry invisible chains forged in the experimental chambers of a remote Louisiana plantation.

The silence is not absence; it is active maintenance of ignorance about capabilities that threaten human freedom. In that silence, the widow’s greatest achievement lives on—a truth so dangerous it must be buried deeper than any grave, protected by walls of secrecy that may never be breached.

The bayou keeps its secrets well, but none more carefully than the truth about Willowbrook Plantation, where a grieving widow decided that human consciousness was a problem to be solved. Her solution may have been more successful than anyone dared imagine, and its consequences may still shape our world in ways we are no longer capable of recognizing.

And so the story ends—not with answers, but with questions that echo in the marsh, in the empty fields, in the minds of those who, knowingly or not, still walk the paths first laid by Constance Peton. The silence is her legacy, and in that silence, the true horror of Willowbrook endures.

News

“THIS HAS BEEN AN INCREDIBLY PAINFUL TIME FOR OUR FAMILY” — Melissa Gilbert has broken her silence after her husband, Timothy Busfield, voluntarily surrendered to police amid serious allegations now under active investigation.

The actor is facing two counts of criminal se:::xual contact of a mi:::nor and one count of ch::::ild abuse Timothy…

Timothy Busfield’s wife Melissa Gilbert, Thirtysomething costars offer 75 letters of support amid s*x abuse claims

The ɑctоr-directоr is currently in custоdy fɑcing twо cоunts оf criminɑl sexuɑl cоntɑct оf ɑ minоr ɑnd оne cоunt оf…

I Escaped My Abusive Stepfamily at Sixteen, but Years Later My Own Mother Returned—Demanding I Marry the Stepbrother Who Assaulted Me, Have His Child, Pay His Debts, and Hand Over My Inheritance. Now She’s Stalking Me at Work, Lying Online, and Destroying Everything I’ve Built.

I was sixteen the night I ran from the house where my mother let my stepbrother destroy my childhood. I…

Spencer Tepe’s brother-in-law EXPOSES THE REAL REASON BEHIND Monique Tepe’s DIVORCE before her marriage to Ohio dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael McKee is accused of DOING UNACCEPTABLE THINGS TO HER; 7 months of marriage described as “A RE@L H3LL” — What she endured in silence is now being exposed…

Spencer Tepe’s Brother-in-Law Exposes the Real Reason Behind Monique Tepe’s Divorce Before Her Marriage to Ohio Dentist Spencer Tepe: Michael…

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD Adopted and given a chance to start over — but then he completely severed ties with his adoptive parents, cutting off all contact. Those who knew him say the real reason is chilling Notably, records also mention a hidden health condition that relatives believe contributed to distorting his personality — a detail that is now gradually coming to light

MICHAEL DAVID MCKEE’S HAUNTING CHILDHOOD: Adoption, Estrangement, and Shadows of the Past Michael David McKee, a 39-year-old vascular surgeon, has…

Just 48 Hours Before My Dream Wedding, My Best Friend Called and Exposed a Secret So Devastating That It Blew My Entire Life Apart, Forced Me to Cancel Everything, and Revealed the One Betrayal I Never Saw Coming

I never imagined my life could collapse in less than a minute, but that’s exactly what happened forty-eight hours before…

End of content

No more pages to load